I have come to realize over the eighteen months I’ve been writing these Music History Mondays that a date-sensitive blog (like this one) is a metaphor for life itself. On some days you just can’t buy a break while on others there are so many different possibilities that choosing one becomes well nigh impossible, a case of feast or famine.

For example. Last week – Monday, April 30th – it was famine. Bereft of a major (or even minor) musical event to write about, I unearthed the fact that on April 30th, 1977 the rock band Led Zeppelin set a new attendance record for a single-act, non-festival ticketed concert, when it played to an audience of 77,229 at the Pontiac (Michigan) Silverdome. This week, today – May 7th – it is feast. And not just any feast; no, today’s date in music history is a cornucopia of gustatory delight; a smörgåsbord the length and breadth of Stockholm; the Carnival World Buffet at Rio Casino in Las Vegas (reputed to be the largest daily pig-out in the world).

Check it out:

- May 7, 1747: Johann Sebastian Bach met with King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) of Prussia in Potsdam.

- May 7, 1824: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 received its premiere at Vienna’s Theater am Kärntnertor/Kärntnertortheater (in English, “Carinthian Gate Theater”)

- May 7, 1825: the death of the Italian composer Antonio Salieri in Vienna, age 74.

- May 7, 1833: the birth of the German composer Johannes Brahms in Hamburg.

- May 7, 1840 (Gregorian calendar; April 25 on the Julian calendar): the birth of the Russian composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky in Votkinsk.

- May 7, 1941 – Glenn Miller and His Orchestra recorded Mack Gordon and Harry Warren’s Chattanooga Choo Choo.

Pick one? Impossible. Please: let us grab our plates, get on the buffet line, and sample something of three of them.

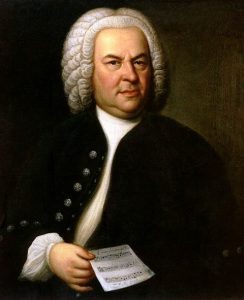

Bach in Potsdam

On May 7, 1747, J. S. Bach visited the King of Prussia – Frederick the Great – at Potsdam. The king was a skilled musician; he played the flute; he composed; and he played the piano. Yes: he preferred the relatively new pianoforte to the harpsichord, and to that end he had 15 of them constructed by the organ/piano builder Gottfried Silbermann. (That number is probably an exaggeration, but it’s the one that has come down to us; however many there really were, two of Silbermann’s pianos remain in Frederick’s Potsdam palace to this day.) Bach was led from room to room and where he played each of them. (He had played pianos before and didn’t particularly like them; he found their action heavy and their trebles weak.) During the course of this “tour”, the king handed Bach a theme of his own composition and asked Bach to improvise a fugue on it, which Bach did (for three voices). On returning home to Leipzig he composed a six-voice fugue based on Frederick’s theme: the justly famous Ricercar a 6. He bundled it together with a number of other works he composed based on the same theme and sent the lot of them off to Frederick as “a musical offering.” The pianist and musicologist Charles Rosen points out that the Ricercar a 6 might very well be “the first piece that a composer knew would certainly be played on a piano.”

Beethoven’s Ninth

The first performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 on May 7, 1824 was one of a handful of the most important and highly anticipated premieres in the entire history of Western music. Beethoven was clinically deaf when he composed the symphony, and not a small bit crazy at the time of its premiere. A marvelous description of the premiere comes to us from the violinist Joseph Böhm, who as a member of the orchestra had a front row seat for the Beethoven’s ludicrous behavior during the performance.

“Beethoven himself ‘conducted’, that is, he stood in front of the conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. He flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts. The actual direction was in [Michael Umlauf’s] hands; we musicians followed his baton only.”

The conductor – Michael Umlauf – had warned the players and singers not to even think about looking at Beethoven during the performance. It was the contralto soloist Karoline Ungar who famously turned the deaf Beethoven around so that he might be aware of the extraordinary ovation the symphony received. According to the previously quoted violinist Joseph Böhm:

“He had to be told when it was time to acknowledge the applause, which he did in the most ungracious manner imaginable.”

(“In the most ungracious manner imaginable”? Goodness: what did he do? Did Beethoven stick out his tongue? Hoist a middle finger? Flash a moon? We can only guess.)

Salieri’s Death

Poor Antonio Salieri. He was a standup guy and a composer of extraordinary competence. He numbered among his many students Franz Liszt, Beethoven, and Franz Schubert, whose musical education he supervised. And yet his enduring fame rests of the entirely false notion that he “killed Mozart.” Here’s why.

In October 1823, Antonio Salieri – the former Kapellmeister the Imperial Habsburg court – was forcibly carried off and admitted to a hospital called the “Vienna Allgemeine Krankenhaus”. He was 73 years old – quite elderly for the time – and had been in failing health for some time. However, it was his rapidly declining mental state that had led to his hospitalization.

Distraught and disoriented, Salieri was caught trying to cut himself with a knife on his second day at the hospital. The rumor flew across Vienna that he had attempted suicide and had, in addition, claimed to have killed Mozart! Never mind that Salieri was physically enfeebled and mentally deranged when he made that claim. Never mind that during his moments of lucidity Salieri denied having had anything to do with Mozart’s death.

Never mind that no plausible “method” has ever been put forward to explain just “how” Mozart might have been killed Mozart and never mind that Salieri had no motive to kill Mozart. (In fact, given their relative fame, popularity, and income, Mozart had much more reason to kill Salieri than Salieri had to kill Mozart!)

Days before Salieri’s death on May 7th 1825, the following report appeared in the Allegemeine musikalische Zeitung:

“Our worthy Salieri just cannot seem to die. His body suffers all the pains of old age and his mind is gone. In moments of hallucination and confusion, they say, he even accuses himself of complicity in the earl death of Mozart: a delusion that no one believes except the poor, bewildered old man himself.”

And that’s where it would have ended but for a one-act play that appeared in 1830 in which a motive for “Salieri-as-murderer” was provided by the Russian poet and playwright Alexander Pushkin, who depicted Salieri as a diligent and serious artist driven to near madness by Mozart’s genius and buffoonery. Pushkin’s play was turned into an opera by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1898 and became the backbone of the play by Peter Shaffer and the movie Amadeus of 1984.

(The movie won eight Academy Awards. It should also have won a ninth, for “Most Historically Inaccurate Portrayal of Two Artists Who Deserve Better: Salieri and Mozart.”)