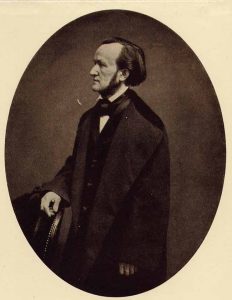

On June 10, 1865 – 154 years ago today – Richard Wagner’s magnificent music drama Tristan und Isolde received its premiere in Munich under the baton of Hans von Bülow (with whose wife, Cosima, Wagner was carrying on an affair).

(The parts of Tristan and Isolde were sung by the real-life husband and wife team of Ludwig and Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld. Having sung the role of Tristan four times, Ludwig dropped dead on July 21, 1865, prompting the rumor than the role of Tristan – one of the most difficult in the repertoire – had flat-out killed him. Malvina was so distraught that though she lived for another 38 years, she never sang again.)

Tristan und Isolde is a three-act music drama, or what Wagner himself called “eine Handlung” (which means “a drama” or“an action”; by mid-career Wagner refused to use the word “opera”, claiming that it represented the debased pseudo-art of anyone not named “Wagner”.) Tristan und Isolde’s libretto (or “poem”, as Wagner would have us call it) was written and its music composed by Wagner between 1855 and 1859.

Wagner based his “poem” on a twelfth-century romance entitled Tristan by Gottfried von Strassburg, who died circa 1210. Wagner’s poem tells the story of two presumed “enemies” – the Irish princess Isolde and the Cornish (southern English) knight Tristan – who fall madly in love when they are duped into drinking a love potion. (Many modern observers – yours truly included – believe that this “love potion” was nothing but a placebo, one that allowed Tristan and Isolde to, like, get in touch with their feelings. Unfortunately, their love for each other is illicit (Isolde is scheduled to marry the King of Cornwall) and unconsummated (despite their best efforts, T and I never manage to “do the dirty”, perhaps because they just can’t stop singing about how much they love each other). In the end, Tristan is cut down by a fellow knight of Cornwall and Isolde, on finding Tristan dying, expires over his now dead body in an orgasmic haze.

Critics of Tristan und Isolde have referred to Wagner’s linked infatuation with sex and death as “perfumed obscenity” and its orgasmic and deathly conclusion as “snuff opera”.

Those nattering nabobs of critical negativism aside, I would happily argue that Tristan und Isolde is Wagner’s single greatest work. There’s nothing else even remotely like it in the repertoire.

Richard Wagner was a great composer. The magical beauty and dramatic power of his music, combined with the breathtaking grandiosity of his artistic vision together created a “Wagner cult”, one that began in his lifetime and lives on to this day. There are “Wagnerians” out there – Wagnerites, Wagnerfiles, and at its most extreme, Wagnerpaths – who will travel across the country to see a Wagner production, across continents and oceans to attend a Ring Cycle, who at least once in their lifetimes will make Hajj to the Wagnerian Mecca that is the Bavarian city of Bayreuth; Wagnerians whose knowledge of Wagner singers and recordings is outdone only by their opinions of same.

There is no other composer in the great history of Western music who has inspired such quasi-religious adulation as Richard Wagner. Like Shakespeare before him and J. R. R. Tolkien, George Lucas, and George R.R. Martin after him, Wagner created an alternative universe that is, for some, a necessary part of their lives.

And yet, for every reverential Wagnerfreak, there is an equally adamant Wagnerphobe, someone who is disgusted by the “Wagner cult” as well as by the man: by his arrogance, his “racial theories”, and his belief in the inherent superiority of all things “German”.

On these lines, a telling Wagner quote:

“I am the most German of beings. I am the German spirit. Consider the incomparable magic of my works.”

It is an unfortunate fact that the more we get to know Richard Wagner the person, the less we like him. Harold Schonberg, for many years the chief music critic for the New York Times was blunt in his appraisal of Wagner, the “man”:

“As a human being, he was frightening. Amoral, hedonistic, selfish, virulently racist, arrogant, filled with gospels of the superman (the superman naturally being Wagner) and the superiority of the German race, he stands for all that is unpleasant in human character.”

And yet this same Harold Schonberg gushed over Tristan und Isolde:

“Never in the history of music had there been an operatic score of comparable breadth, intensity, harmonic richness, massive orchestration, sensuousness, power, imagination, and color. The opening of Tristan was to the second half of the nineteenth century what [Beethoven’s] Eroica and Ninth Symphonies had been to the first half: a breakaway, a new concept. What Tristan does is to describe inner states, with a kind of power and imagination that peels off layer after layer of the subconscious. It abounds in symbols: symbols of Night, Day, eroticism, the dream world, Nirvana. Whatever its meaning or meanings, Tristan und Isolde brings together man and woman, and probes their deepest impulses.”

For most of us – like Harold Schonberg – our attitude towards Wagner today can be summed up in two words: mixed feelings. Wagner’s artistic greatness cannot be questioned, whether or not we like the subject matter (or length!) of his works. Yet his megalomania, narcissism, racism, anti-Semitism, fanaticism, and other like “isms” place him among the most repellent figures in the wide history of Western music.

Wagner believed that his artistic muse required the creature comforts of a Saudi Prince and that his “genius” entitled him to anything he wanted. He was shamelessly up front about it, declaring in 1864:

“I am a different kind of organism. I have hyper-sensitive nerves. I must have beauty, splendor, and light. The world ought to give me what I need! I cannot live the wretched life of a town organist like Bach! Is it such a shocking demand, if I believe that I am due the luxury I enjoy?”

Emma Herwegh, the wife of Wagner’s friend, the poet Georg Herwegh had no patience for Wagner, who she wrote-off as:

“This pocket-size edition of a man, this folio of vanity, heartlessness and egoism.”

Conversely, Heinrich Porges, a German-Jewish writer and choral conductor who worked with Wagner understood Wagner. He wrote:

“Such demonic personalities cannot be judged by ordinary standards. They are egoists of the first order, and must be so, or they could never fulfill their mission.”

Now, many well-meaning observers would argue – the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche among them – that Wagner “the man” and Wagner’s “music” should be considered as two separate entities; hey, look, Ty Cobb might have been a first-class jerk, but that doesn’t change the fact that he had 4189 hits and a career batting average of .367, the highest ever.

But in fact, we cannot separate Wagner the “man” from his “music”. According to Wagner himself, his life and work constitute a single, indivisible entity; his attitudes and beliefs – controversial (even loathsome) that they may be – lie at the heart of his mature work.

But most importantly, it is Wagner himself that lies at the heart of his stage works: his absolute, autobiographical identification with his leading male characters, starting with the martyred, anti-aristocrat, populist hero Cola di Rienzi, the title character of his first major opera – Rienzi – of 1840. In The Flying Dutchman of 1841, Wagner is the Dutchman: a tragic, lonely, super-natural character in search of redemption through love. In Tannhäuser of 1845, Wagner is Heinrich Tannhäuser, a medieval Orpheus struggling between the pleasures of the flesh and the spirit, in search of redemption through love. In Lohengrin of 1848, Wagner is Lohengrin, a supernatural knight who has stepped into the world of mortals in search of a woman’s love. Just so, Wagner is the “revolutionary hero” Siegfried in the Ring Cycle; he is the fearless, self-taught singer Walther von Stolzing in The Master-Singers of Nuremberg; he is the world-redeeming, Holy Grail-finding knight Parsifal in Parsifal.

Most of all, Wagner is Tristan of Cornwall, a loyal and honorable knight driven to near-madness by the love for a woman he can never possess. Tristan und Isolde is Wagner’s single most autobiographical work, and here’s why.

Having fled Germany in 1849, Wagner and his wife Minna settled in Zurich Switzerland. Wagner chose Zurich because it was the home of one of his principal patrons, a silk merchant and Wagner-Head named Otto von Wesendonck. Herr von Wesendonck’s passion for Wagner’s music was soon shared by his young and very beautiful wife Mathilde, with whom Wagner fell madly in love. Wagner’s wife Minna discovered what was going on (or at least, what she thought was going on) between her husband and Mathilde, and she kicked Wagner out. All of this tsuris corresponds precisely with the writing of the poem and the composition of Tristan und Isolde, which in hindsight can be seen for what it is: a diary of Wagner’s own roller-coaster emotions about loving the wife of his “king” (his principal patron!): a woman he knew he could never possess.

Tristan und Isolde remains the best evidence that for all the gossip and innuendo, Wagner and Mathilde’s relationship was platonic: non-physical. Barry Millington asks the key question when he writes:

“Could that monumental expression of yearning [that is Tristan und Isolde] have been composed while its creator was in the throes of ecstasy? Wagner’s love for Mathilde indeed wrung from him some of the most passionate music he ever composed, but it is surely the effusion of one who is denied the ultimate satisfaction.”

There we have it. In a nutshell, we cannot separate Wagner the “man” from Wagner the “artist”; they are one and the same. We’ve got to embrace the whole, controversial Wagnerian package, because every part is essential to the whole, and the whole includes one of the most compelling bodies of art ever created by a member of our species.

For lots more on Wagner and his dramatic works, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses Survey The Music of Richard Wagner.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More