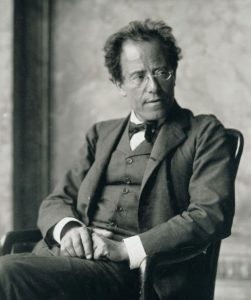

We mark the passing, on May 18, 1911 – 109 years ago today – of the composer and conductor Gustav Mahler. Mahler, who was born on July 7, 1860 in the Bohemian village of Kalischt, died all-too-young in Vienna, two months shy of his 51st birthday.

But before moving on to the painful circumstances of Mahler’s death and his “last words”, we would mark the painful circumstances of the death of his exact contemporary, the Spanish-born composer and pianist Isaac Manuel Francisco Albéniz Y Pascual, or simply Isaac Albéniz.

Albéniz was born on May 20, 1860 – 39 days before Gustav Mahler – in Camprodon, a town in northern Catalonia not far from the French Border. A spectacularly gifted child, he made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of four and began his concert career at the age of nine. As a composer, he embraced the music of his native Spain in 1883 at the age of 23, when he began composing avowedly “Spanish-styled” works. His great masterwork is Iberia a set of twelve virtuosic piano works composed between 1905 and 1909, completed just three months before his death. (For those interested in an examination of Albéniz’ Iberia – and, if you’ll excuse me, that should include pretty much any sentient human being – I would humbly direct your attention to Lecture 18 of my Great Courses/Teaching Company survey, “The 23 Greatest Solo Piano Works”, which is dedicated to Albéniz’ Iberia. The course can be examined and downloaded at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.”)

The adult Albéniz was short, round, bearded, and a legendary gentlemen to everyone that knew him. The French music critic Georges Jean-Aubry remembered Albéniz this way:

“The kindness and generosity of the man were unsurpassable. He was unstinting in his praise of others; his talk was always of friendship, affection, or joy. I never saw him otherwise.”

The French pianist and teacher Marguerite Long praised him for his “kindness and devotion” while the composer Paul Dukas summed him up as being:

“a Don Quixote with the manner of [a] Sancho Panza.”

(For our information, Paul Dukas’ most famous work, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, received it’s premiere on May 18, 1897 – 123 years ago today – in Paris, with Dukas conducting.)

Sadly, Albéniz was not a good steward of his own health (to put it mildly!). He was obese, smoked cigars incessantly, and abused alcohol. As an adult he suffered from colitis, which impacted his diet not a whit; according to his principal English-language biographer Walter Allen Clark:

“When dining out, he was wont to order all the dishes at once and then to stir them together into a mishmash, which he devoured rapidly and with great relish. Albéniz enjoyed strong foods, especially Catalan sausage. He liked nothing more than to curl up with a big salami and wash down the slices with generous swigs from a flask of gin. But these habits did not agree with his stomach and sometimes caused him to lose its contents. [Italics mine.] Undaunted after such episodes, he would return to his chair and continue eating.”

Yes indeed, TMI.

Albéniz’ body simply couldn’t take it all, and by 1908 – when he was 48 – it began to break down. Incapacitated with uremia (“a raised level in the blood of urea and other waste compounds due to kidney failure”), his illness cascaded and his health broke while he was staying in the spa town of Cambo-les-Bains in the south of France. He died on this day in 1909, just two days before his 49th birthday, and exactly two years to the day before the death of Mahler.

Gustav Mahler was many things: a prodigiously gifted pianist and composer, among the greatest conductors of his time (and among the greatest opera conductors of all time), a husband and a father. Easy going and easy to get along with he was most certainly not. The singers and instrumentalists who performed under his baton loathed him: to them, he was a small, pale tyrant who gave them no quarter and rehearsed works they thought they knew for hour after unending hour. Management, likewise, usually detested him, with his endless artistic demands and constant threats to quit if those demands were not met. But no one could argue with the results, because audiences loved him, and everywhere he went he raised the level of performance to the degree that his actions and behaviors were tolerated; had to be tolerated.

In 1897, the 37 year-old Mahler reached the pinnacle of the conducting world when he was appointed the Music Director of the Vienna Imperial Opera. (Mahler’s hiring in Vienna is discussed at some length in my Dr. Bob Prescribes post of April 21) True to form, among Mahler’s very first acts as music director in Vienna was to write out his resignation letter and put it in the top drawer of his desk, believing as he did that he could not perform his job to the highest standards unless he was prepared to resign at the drop of a baton.

Mahler’s resignation letter sat in that drawer for ten years.

In the years between 1897 and 1907 Mahler led the Vienna Imperial Opera to what was very likely the very pinnacle of its artistic success. He composed his Symphonies Nos. 4 through 8 and the five Rückert-Lieder and five Kindertotenlieder, both works for voice and piano.

In February of 1902, the 41-year-old Mahler managed to knock-up Alma Schindler, a beautiful and talented young woman 19 years his junior; they were married some four weeks later and together had two little girls, Marie and Anna.

But then 1907 rolled around, a year that Mahler and his family would happily have chosen – had they been given the choice – to have done without.

We will explore in detail the events of 1907 at some other time. Please, for now, suffice it the following.

In late May of 1907, for reasons both personal and professional, Mahler found it necessary to submit his resignation from the Vienna Imperial Opera, effective immediately.

Just weeks later, on July 11, 1907, Mahler’s eldest daughter Marie – 5 years old and nicknamed Putzi – died of scarlet fever and diphtheria after a terrifying two-week illness.

Just a few days after that, Mahler himself was diagnosed with having what was thought, at the time, to be potentially fatal heart disease. According to his wife Alma, “this diagnosis was the beginning of the end for Mahler.”

Mahler had a valvular dysfunction that could be traced back to inflammation due to a case of tonsillitis. His heart valves weren’t snug; they didn’t close completely and leaked a bit. In Mahler’s case the leakage was minimal; his “heart disease” was, in itself, by no means terminal. But Mahler’s heart was compromised, and that did in fact lead to his death four years later.

On January 1, 1908, Mahler led his first performance as the principal conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. He directed the Met for two seasons before moving over to the New York Philharmonic. On October 25, 1910, he arrived in New York with a sore throat to conduct his second season with the Philharmonic. The season was a success, with Mahler conducting in New York (at Carnegie Hall), in Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, and Utica (New York). But Mahler’s sore throat just wouldn’t go away. Unknown to everyone, he was already dying.

On February 21, 1911, his body temperature suddenly spiked to 104 degrees. Doctors were called in, Mahler’s blood was tested, and it was discovered that he was infected with the streptococcus bacteria. The diagnosis: subacute bacterial endocarditis – a very serious ailment afflicting hearts which, like Mahler’s, have suffered valvular disease. Most likely Mahler had picked up the bacterial bug sometime during the summer of 1910. In those days, before antibiotics, subacute bacterial endocarditis was almost certainly fatal. This last bit – the fatal part – was kept from the Mahler.

It took three agonizing months for Mahler to die. He was so weak that he often had to be fed by hand. Finally, it was decided that Mahler should leave New York, return to Europe, and be examined by the eminent bacteriologist Dr. Chantemesse, in Paris. Alma recalled:

“Our cabin was booked, the packing was done, and Mahler was dressed. A stretcher was waiting, but he waved it aside. He looked as white as a sheet as he walked unsteadily to the lift, leaning on Dr. Frankel’s arm. The elevator attendant kept out of the way until the last moment, to hide his tears, and then took him down for the last time. The huge hotel lobby was deserted; an automobile was waiting at a side entrance. I went back to the office to pay the bill and to thank the office staff for all they had done for us during those weeks. They all came out and shook hands. [The manager told me]: ‘We cleared everyone out of the lobby – we knew Mr. Mahler wouldn’t like to be looked at.’

Blessed America! We never met with any such proof of true sensibility during our subsequent weeks in Europe.”

The trip to Paris was a waste of time. Again, Alma recalled:

“Dr. Chantemesse, the celebrated bacteriologist, now made a culture from Mahler’s blood and after a few days he came to us in great delight with a microscope in hand. I thought some miracle had happened. He placed the microscope on the table. ‘Now, Madame Mahler, come and look. Even I – myself – have never seen streptococci in such a marvelous state of development. Just look at these threads – it’s like seaweed.’ He was eager to explain. But I could not listen. Dumb with horror, I turned and left.”

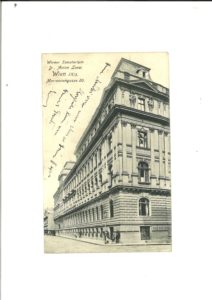

Alma took Gustav home to Vienna to die. They arrived on May 13, 1911; Mahler was installed at the Loew sanitarium at Mariannengasse 20, a high-end private hospital in Vienna’s 9th district. Seized and shut down by the Nazi’s in 1938 (the Loew family, which was Jewish, fled Vienna), the building is occupied today by offices and residential apartments.

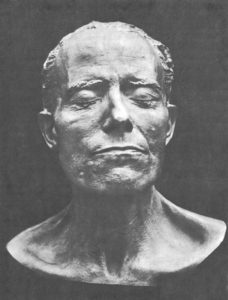

Mahler lived for another five days at the sanitarium. Alma finishes the story:

“[So typical of Mahler], he read works of philosophy up to the very end. The last book he read was The Problem of Life by Eduard von Hartmann. He tore the pages from the binding, because he had not the strength to hold more than a few pages at a time.

During his last days and while his mind was still unclouded his thoughts often went anxiously to [Arnold] Schoenberg. ‘If I die, he will have nobody left. Who will protect him from the mob?’

Then the end. [It was shortly after 11 o’clock in the evening, May 18, 1911.] Mahler lay with dazed eyes; one finger was conducting on the quilt. There was a smile on his lips and twice he said: ‘Mozart!’”

For much more on the life and music of Gustav Mahler, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses-Teaching Company “Great Masters” biography of Mahler.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More