I spent the first few months of this year composing a set of six etudes for piano (posted on Patreon on April 2 and 9). As per my usual MO, I spent a couple of days prior to starting work listening to and/or reading through a batch of etudes by the usual suspects – Chopin, Liszt (I was once given a small, rectangular pad of paper labeled “Chopin Liszt” – “shopping list”), Rachmaninoff, Debussy, and Ligeti – in order to get my head and my ears in the right place.

Again, typical of my compositional process, once I started writing I put such listening aside. At that point, it could only get in my way and remind me of how utterly inadequate I am when compared to the heavyweights named above.

“Etude” means “study”. A musical “etude” is a technical study, a work that isolates and emphasizes some particular aspect (or aspects) of technique. Etudes have and will continue to be composed for every instrument for pedagogic purposes. With all due respect to Beethoven’s student and friend (and the teacher of Liszt) Carl Czerny (1791-1857), who wrote virtually thousands of piano etudes (his last published work, Opus 861, is titled “30 Studies for the Left Hand”), the person who transformed the keyboard etude from pedagogic art to the level of high art was Frédéric François Chopin (1810-1849). Chopin composed a total of 27 etudes for piano, twelve of which were published as Op. 10 in 1833; an additional twelve were published as Op. 25 in 1837; and then three more etudes in 1839 that were published without opus numbers. Chopin’s etudes are not merely “studies for the piano” but collectively works of the highest musical art, works that not incidentally constitute some of the greatest and most innovative software for a then brand new piece of hardware: the metal-harped, double-escapement pianos that emerged in the late 1820s and 1830s. Before Chopin, no top tier pianist-composer saw fit to compose piano etudes. After Chopin they pretty much all did, including those named at the top of this post.

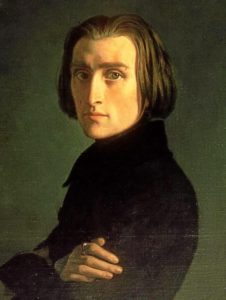

By definition, etudes composed by top-tier pianist-composers will be difficult to play. But as we all know from watching competitive diving, skating, and gymnastics, there is such a thing as degrees of difficulty. When it comes to etudes for piano, at the highest, most technically challenging level are the aptly named Transcendental Etudes of Franz Liszt.

Liszt’s music and pianism have been discussed frequently in my Music History Monday and Dr. Bob Prescribes posts. Music History Monday for November 7, 2016, dealt with the first performance of Franz Liszt’s Dante Symphony, and that of October 22, 2018, celebrated Liszt as “The First Rock Star”. Dr. Bob Prescribes for September 26, 2018, featured Cyprien Katsaris’ crazy-good performance of Liszt’s piano transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies, and that of January 15, 2019, celebrated Alan Walker’s brilliant, three-volume biography of Liszt. Likewise, my Great Courses/Teaching Company surveys have featured Liszt and his music to a degree only exceeded by J. S. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, and Verdi.

Why all this Liszt? Find out, and see the prescribed recording, only on Patreon!