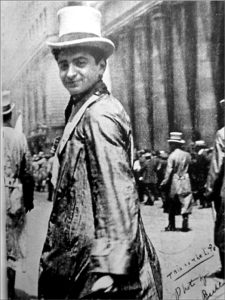

Irving Berlin (born Israel Isidore Beilin, 1888-1989) was the greatest songwriter ever to live and work in North America. His songs – for which he wrote both the words and music – capture the spirit and chronicle the events of the first half of twentieth century America in a manner far beyond that of any other single songwriter. Among Berlin’s great contemporaries there were lyricists who wrote cleverer, more sophisticated lyrics and composers who pushed the formal structure and harmonic complexity of the popular song more than Berlin. But Berlin’s songs united the personal and the topical in words and melodies that had an almost universal appeal. Writes Robert Kimball:

“The ability to capture and represent the human experience in a simple, direct way is what great songwriting is all about. And that is where Irving Berlin had no peer.”

(BTW, this doesn’t mean that Berlin couldn’t create a great rhyme; rather, when he does so, it is entirely in the service of the song and never to show us how very clever he is. For example, the lyric to Let’s Have Another Cup of Coffee, written in 1932 during the darkest days of the Depression, in which he rhymes “umbrella” with “Rockefeller”:

Verse: Why worry when skies are gray Why should we complain? Let's laugh at the cloudy day Let's sing in the rain. Songwriters say the storm quickly passes That's their philosophy; They see the world through rose-colored glasses Why shouldn't we? Chorus: Just around the corner, There's a rainbow in the sky, So let's have another cup o' coffee And let's have another piece o' pie! Trouble's just a bubble, And the clouds will soon roll by, So let's have another cup o' coffee And let's have another piece o' pie! Let a smile be your umbrella For it's just an April show'r Even John D. Rockefeller Is looking for the silver lining. Mister Herbert Hoover Says that now's the time to buy, So let's have another cup o' coffee And let's have another piece o' pie!)

The statistics regarding Berlin’s songs are head spinning. Of his over 1500 songs, 899 were registered for copyright. 451 of these songs – over half – became hits. 282 of them achieved a “top ten” status in sheet music sales and/or recording sales. And 35 of them reached “number one”, a record that along with DiMaggio’s hitting streak will simply never be equaled, let alone bettered.

Berlin began his career as a street singer and as a lyricist. As a lyricist, unlike his great contemporaries, he was virtually unschooled. (Talk about well-schooled lyricists: Jerome Kern’s greatest collaborator was lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, who attended Columbia University and Columbia Law School. Richard Rodgers lyricist Lorenz Hart attended Columbia University School of Journalism. George Gershwin’s lyricist, his brother Ira, attended CCNY: City College of New York. Cole Porter, who like Berlin wrote both his words and music graduated from Yale in 1913.)

Irving Berlin education came from the School of Hard Knocks. The son of a synagogue cantor, he immigrated from the Russian Empire to the United States at the age of 5 in 1893 after his village was destroyed in a pogrom. He grew up in abject poverty in a tenement at 330 Cherry Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His formal schooling ended in 1901 at the age of 13 when his father died at the age of 53 from bronchitis. The young Izzy made his money – what there was of it – selling newspapers, then singing in the streets for coins. Jobs as a singing stooge (see yesterday’s Music History Monday for an explanation) and as a singing waiter in some of the roughest, lowest dives anywhere to be found – in Manhattan’s Bowery and Chinatown – got him off the streets. At the age of 18, he wrote his first song in collaboration with a pianist named Nick Nicholson: an utterly forgettable ditty titled Marie from Sunny Italy that earned him a 37-cent royalty back when 37-cents was, well, still just 37-cents. But he saw his name in print and was bitten by the bug (for anyone who has ever seen his or her name on the cover of a commercial book or music title, you know exactly what I mean!).

For the next few years Berlin worked primarily as a lyricist, teaming up with the composer Ted Snyder to write a series of increasingly popular songs, climaxing with their 1909 hit My Wife’s Gone to the Country. The song sold over 300,000 copies of sheet music. The 21 year-old Irving Berlin, who just a few years before had been a singing waiter in the lowest of dives, suddenly had some real money in his pocket. Even more importantly, he convinced himself that he should be writing both the words and music of his songs. He put it this way:

“By writing both words and music, I can compose them together and make them fit. I sacrifice one for the other. If I have a melody I want to use, I plug away at the lyrics until I make them fit the best parts of the music, and visa versa. Nearly all other writers work in teams, one writing the music and the other the words. They are either forced to fit someone’s words to their music or someone’s music to their words. Latitude – which begets novelty – is denied them, and in consequence both lyric and melody suffer.”

Berlin’s conviction that he must write both the words and music of a song came at a most propitious moment. A ragtime craze was sweeping the country. Ragtime was created in the late nineteenth century by Black American pianists in New Orleans and the southern Mississippi River region. It synthesized the marching band music so popular at the time with West African rhythmic practice: a pianist’s left hand thumped out a steady “HUT-two” march beat while the right hand layered a rhythmically contrasting, off-the-beat (or “syncopated”) part atop, literally making the beat “ragged”. By the early twentieth century, ragtime had become a national craze (and for those arbiters of musical morality, a national disgrace: music consisting of the the basest of rhythms, rhythms that would make young people aware of their bodies rather than their spirits!). A new, post-minstrel show species of race song emerged called “coon songs”, songs that featured black “dialect” lyrics along with the syncopations of ragtime. These songs were frankly racist, often grotesquely so, but they served as a liberating antidote to the sappy, Victorian tearjerkers that had dominated the American musical scene through the late nineteenth century.

(An interesting and apt comparison: just as many American’s were embracing the anti-Victorian, sexually liberating, African-inspired spirit of ragtime in the first years of the twentieth century, so Parisians and such artists as Picasso, Matisse, and Derain were being inspired by the anti-Victorian, sexually liberating essence of African art being exhibited in Paris during the first years of the twentieth century. Understood this way, we can see that Berlin’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band of 1911 and Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring of 1912 grew out of the same general artistic environment!)

Irving Berlin got on the ragtime bandwagon early and often, writing a series of so-called “ragtime songs” with such titles as Yiddle on Your Fiddle (Play Some Ragtime); That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune (Mendelssohn Rag) (a ragtime version of Mendelssohn’s ubiquitous “Spring Song”), He’s a Rag Picker, The Ragtime Soldier Man, and That International Rag. But it was Alexander’s Ragtime Band, a song created in an 18-minute burst of inspiration in 1911 that made the Berlin legend. It sold over a million copies in 1911. Then it sold over a million copies in 1912, at which point it was rightly hailed “as the biggest song hit ever known.” …… Continue Reading, and see the prescribed recordings, only on Patreon!