We mark the death on July 27, 1924 – 96 years ago today – of the composer and pianist Ferruccio Busoni, who great fame rests on having invented the ice-smoothing machine popularized by none-other-than Charles Schulz’s Snoopy.

Nah, I’m just messing with you: it was Frank Zamboni, 1901-1988, who invented the ice-thing in 1949.

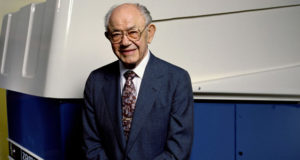

We’re here to talk about Ferruccio Busoni, who was born in Empoli, Italy – a suburb of Florence – on April 1, 1866 and died on this day at the age of 58 in Berlin.

But before moving on to Signore Busoni, a tip-of-the hat to his countryman, Antonio Vivaldi – Il Prieto Rosso, “The Red Priest” – who died on this day in 1741 in Vienna, age 63. Vivaldi’s birth on March 4, 1678 was the subject of my Music History Monday post on March 4, 2019; I would invite you to check it out.

Ferruccio Busoni was a phenomenon, a figure almost unique in Western music, a man and musician impossible to pigeon-hole. He was a virtuoso in pretty much every field of music he chose to explore. He was a pianist of other-worldly ability; a visionary composer possessing the very highest technical skills; a conductor of supreme intelligence; a brilliant musical thinker: a profoundly knowledgeable musician who, as a composer, managed to merge the past with the modernist impulse of the turn-of-the-twentieth century.

(For our information, excepting his skills as a conductor, every one of these aspects of Busoni’s virtuosity are on display in his Fantasia Contrappuntistica for Piano, which will be the subject of tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post.)

Moments ago, I said that Busoni was a phenomenon, a figure impossible to pigeon-hole. His was a life and career of dualities, often mutually exclusive dualities. For example, more than anything, Busoni wanted to be acknowledged as a composer. But as far as he was concerned, he was cursed, because as one of the very the greatest pianists of his time, the audiences and critics of his day (and ours, as well) were not prepared to acknowledge him as a great composer as well. George Bernard Shaw went so far as to advise Busoni that if he wanted to be as famous a composer as he was a pianist, and we quote Shaw:

“You should compose under an assumed name. It is incredible that one man could do more than one thing well; and when I heard you play, I said, ‘It is impossible that he should compose: there is not room enough in a single life for more than one supreme excellence.’”

The duality of Busoni’s ethnicity offers a key to understanding his artistic makeup, though it was also something that led to grief in his own lifetime. Busoni was born an Italian in Italy but lived most of his creative life in Germany. The Italians regarded him as a deserter, the Germans as an outsider. His Italian father taught him Bach; his half-German mother taught him Italian opera. His musical tastes followed his ethnic duality. According to the Busoni scholar Larry Sitsky:

“He was always attracted to [German music] for its solidity, its sense of form, of organization, and of scholarship, yet he never lost his [Italian] love of melody. And whereas his earlier works were steeped in the German tradition and dedicated to Brahms, his last period was almost purely melodic and clearly closer to his Italian roots.”

Biographical Background

Busoni was born on April 1, 1866 in Empoli, a smallish Tuscan village on the Arno River 12 miles southwest of Florence. His father, Ferdinando, believed that a child’s name influenced his future success. So – taking no chances – he named his first, and, as it turned out, only child after a veritable host of famous Tuscans: Ferruccio Dante Michelangelo Benvenuto Busoni.

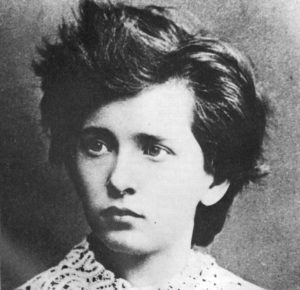

Ferruccio’s father Ferdinando Busoni (1834-1909) was a clarinet virtuoso who made his career touring Europe and concertizing. Ferruccio’s mother Anna was a gifted pianist who was both her husband’s accompanist and a soloist in her own right, concertizing successfully in an age when you could count the number of professional touring women pianists on the fingers of Captain Hook’s right hand (yes, that’s the one with the fingers). Here’s an example of what she was up against. In 1869, when the couple concertized in Paris for the first time, the following review appeared in L’Art musical, on April 8, 1869:

“Madame Busoni was beyond all praise. Under her steely touch the pianoforte sings, shudders, and becomes a complete orchestra in itself. In the Quintet of Schumann, she showed a loftiness of style and a brilliance of execution which one would never have believed possible from the fingers of a mere woman!”

Ferruccio grew up, alternately, on the road with his parents, or in the northern Italian city of Trieste, where his mother’s family lived. His crazy talent was recognized early, and it was his father the clarinetist rather than his mother the pianist who took charge of his piano lessons when Ferruccio was seven years old. It was tough love. Busoni recalled:

“My father knew little about the piano and was erratic in rhythm, so he made up for these shortcomings with an indescribable combination of energy, severity, and pedantry. For four hours every day he would sit by me at the piano, with an eye on every note and every finger. There was no escape or interruption except for his explosions of temper, which were violent in the extreme. A box on the ears would be followed by reproaches, threats, and terrible prophesies, after which the scene would end in great displays of paternal emotion, assurances that it was all for my good, and so on to a final reconciliation – the whole story beginning again the next day.”

Within a year, the now eight-year-old Ferruccio made his public debut in Trieste and had begun composing. A brief stint in Vienna followed, and it soon became clear that his pianism and compositional voice were going to find much more sympathy in the German-speaking north than in Italy. From the beginning, there was an intelligence and gravity to his playing that went far beyond his years and impressed the bejeesus out of the usually jaded German and Austrian critics. On February 13, 1876, the Viennese critic Edward Hanslick – who would have given God, country, his mother and apple strudel a bad review if he believed it warranted – wrote of the not-quite-yet ten-year-old Busoni:

“It’s a long time since an infant prodigy appealed to us as much as little Ferruccio Busoni. Precisely because there is so little of the infant prodigy about him, and so much that suggests a good musician [and] a real composer. His playing is fresh and spontaneous, with the kind of musical awareness that is difficult to define but immediately recognizable. [His compositions] reveal the same musical awareness which we enjoyed so much in his playing; no sign of precocious sentimentality or contrived effect. On the contrary: a remarkable seriousness and maturity which suggests a devoted study of Bach.”

In 1878, at the age of twelve, Busoni’s family moved to Graz – in Austria – so that he might study with the composer Wilhelm Mayer. The cliché applies: from there, the rest is history. Yes, there would continue to be some struggles; Busoni would never be financially well off, and from a fairly young age he lived the difficult life of the traveling virtuoso. But by the time he completed his studies with Mayer there was never any question that he would succeed as a musician; by the age of 17, he was already considered one of Europe’s top pianists. His astonishing talent opened doors wherever he went; by the time he was twenty he had met Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, and Mahler. He had become a close friend of Karl Goldmark and something of a protégé of Johannes Brahms.

In 1894, at the age of 28, Busoni settled in Berlin, which remained his base-of-operations for the rest of his life (excepting a period in Switzerland during World War One). His concert tours took him everywhere, from Moscow and Madrid to San Francisco; from that glorified orange-grove known as Los Angeles to St. Petersburg and Palermo. His was not an easy life. In 1895, at the age of 29, he even wrote a poem about it:

Where is my time-table? How do I get there? Ah! Page one hundred: here’s the only train. Change trains? Can I risk it? Three minutes to spare. No sleeping car? No use to complain. Next morning, at eleven, half-awake And shivering, I arrive. A man comes up. ‘Make haste! The rehearsal is waiting! You must take A cab at once!’ No time for a bite to eat. No time to change or wash. ‘You’re rather late,’ Says the manager. ‘You should know that The rehearsal is open to the public. We’ve been Waiting for you for a half-an-hour.’ Straight to the stage – play as best I can – Hungry and dirty, fingers quite frozen, Finally, done! Why, is that the critic? ‘He’s an old man; You can’t expect him to attend a concert at night.’ The concert’s a success – but what difference does that make? The critic writes about how he heard me play at the rehearsal. Encore? No time. I seize my coat and hat, For the station is a good way off. Onto the train just as the whistle blows, On to the next place, supperless again, Clammy with sweating, still in evening clothes, Tomorrow the rehearsal is at ten.

I don’t know about you, but I get tired and irritable just reading that! Do I have to tell you that Busoni became increasingly disenchanted with his life as a touring pianist? By 1904, his disgust with his life as a performer was evident, writing in a letter to his wife while on tour in the United States:

“The artist exists only for artists! The public, the critics, the schools, and the teachers are nothing but stupid and harmful parasites!” (Thank heavens he left out “bloggers”!)

Busoni’s are harsh words, admittedly written in the “heat” of the moment. But honest words as well, words that betray Busoni’s desire to settle down and be a composer. Sadly, that was never quite to be. He remained a reluctant virtuoso; playing the piano was his day gig and he composed when he could.

Through the first years of the twentieth century, Busoni the composer found himself increasingly drawn to musical experimentation and the avant-garde, and in 1907 he had his breakthrough year. He wrote a pamphlet, entitled Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, in which he laid out his essential artistic tenets, chief among them that the experiments of the present should be combined with the musical structures of the past, so as:

“[not to] overthrow something existing but to recreate something that [already] exists. Everything experimental from the beginning of the twentieth century should be used, incorporated in the coming finality.”

Precisely what that “coming finality” might actually “sound like”, Busoni never quite specified. However, if we may use the example of his Fantasia Contrappuntistica for piano as a guide, what Busoni espoused was the freedom for composers to use any musical tool their expressive needs required, provided that, one, they had mastered proper compositional technique; two, that they were on intimate terms with the music of the past, particularly that of Bach and Mozart; and, three, that they structured their music so that it would be intelligible for performers and audience alike. In this way, Busoni believed, a piece of music would become part of the great, historical continuum: true to the past, relevant to the present, and structurally sound enough to survive the tests of time and live into the future.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More