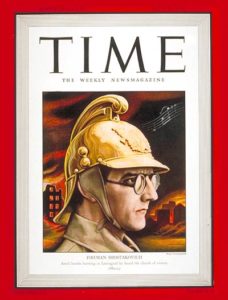

July 20th was a very important date in the life of the Soviet composer Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich. On July 20, 1942 – 78 years ago today – he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, wearing his Leningrad firefighter’s helmet and becoming, all at once, an international symbol for the Soviet struggle against the invading German horde. On this date in 1962 – 58 years ago today – Shostakovich completed his Symphony No. 13, subtitled “Babi Yar”, itself a stunning indictment of Soviet anti-Semitism and truly, the entire Soviet system. How and why he managed to get away with composing and premiering such a symphony without being strung up by his short-‘n’-curlies will be the subject of tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post. Finally, on this day in 1964 – 56 years ago today – Shostakovich completed his String Quartet No. 10 in A-flat major, Op. 118. Yes indeed, July 20 was an important date in the life of Dmitri Shostakovich.

But before we can get to Shostakovich and that Time magazine cover, we’ve got two other events to observe from this day in music history.

We begin with a call-out to the songwriter, guitarist, and fusion bandleader Carlos Santana, who was born on this day in 1947 – 73 years ago today – in Autlán de Navarro, in Jalisco, Mexico. While still a child, Santana’s family moved first to Tijuana and then to the Mission District of San Francisco, where he attended James Lick Middle School and Mission High School. Although he was accepted at California State University, Northridge and Humboldt State University, he chose not to attend college. Instead, the San Francisco music scene of the 1960s became, by his own admission, his “university:”

“If I would go to some cat’s room, he’d be listening to Sly [Stone] and Jimi Hendrix; another guy to the Stones and the Beatles. Another guy’d be listening to Tito Puente and Mongo Santamaria. Another guy’d be listening to Miles [Davis] and [John] Coltrane. To me, it was like being at a university.”

Santana and his bands, which feature a fusion of rock ‘n’ roll and Latin American jazz, have had a huge impact on me since I bought his second LP – Abraxas – in 1970, when I was 16 years old. It was at just around that time that I saw him perform at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, which was my first rock concert and as memorable as my first kiss!

Happy birthday, baby! Love you.

Here’s a timely item that could very well have occupied this entire post had July 20 not been such an important day in the life of Dmitri Shostakovich. On July 20, 2009 – 11 years ago today – the American singer and songwriter Jackson Browne (born 1948) settled his lawsuit against Senator John McCain and the Republican Party. The McCain campaign had used Browne’s 1977 hit Runnin’ on Empty without permission in a McCain campaign video during his bid for the presidency in 2008. Hearkening back to a time of civility and graciousness that has virtually disappeared from Republican politics today, the McCain people and the Republican party apologized for using Brown’s song in the video, and stated that McCain himself “had no knowledge of, or involvement in, the creation or distribution of the video.”

The unauthorized use of music by political campaigns is nothing new and continues to this day. You see, composers and songwriters assign the “rights” to their works to performing rights organizations, either ASCAP (“American Society of Composers and Publishers) or BMI (“Broadcast Music, Incorporated”; I myself have been a member of BMI for nearly 40 years). Campaigns can get around asking an individual songwriter for permission to use a song by going through the back door – as it were – by getting permission directly from ASCAP or BMI, neither of which will ever turn down a licensing fee.

Unfortunately, such use of a song implies an endorsement of the candidate by the recording artist, which can cause some very bad feelings if the artists themselves did not authorize the use of their work. Such unhappiness over “unauthorized use” has reached a pitch of ugly during the last five years. The list of recording artists who have demanded that Donald Trump cease and desist using their songs at his rallies and in his ads reads like a who’s who of everyone, Ted Nugent excluded. Among those who have demanded Trump discontinue using their songs are Adele, Aerosmith, Elton John, REM, The Rolling Stones, Queen, Twisted Sister, Rihanna, Pharrell Williams, and the estates of Prince and Tom Petty. But most contentious is Trump’s use of the music of Neil Young, from the moment he announced his candidacy at Trump Tower on June 16, 2015 to the “not-exactly-a-campaign-rally” at Mount Rushmore earlier this month. Despite Neil Young’s unequivocal and very public disdain for Trump, and Young’s demand that ASCAP void its contract with the Trump campaign, it remains to be seen whether ASCAP will actually do so. We’ll be following this story; more at 11!

Shostakovich on the Cover of Time magazine

On Sunday, June 22, 1941, Dmitri Shostakovich had the hottest of dates: he and his pal Isaac Glikman planned to attend a soccer match double-header (Dynamo versus Zenith) and then go out to dinner. Sadly, none of it ever took place. On their way to the stadium there in Leningrad (also known, during the twentieth century, as St. Petersburg and Petrograd) they heard Vyacheslav Molotov’s radio broadcast announcing the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Joseph Stalin – who had been receiving solid intelligence about the Nazi invasion plans for months – was stunned; rendered virtually speechless. Alexander Solzhenitsyn later wrote:

“Not to trust anybody was typical of Stalin. All the years of his life did he trust one man, and that was Adolf Hitler.”

Oh, the irony of it all!

Back in Leningrad, the 35-year-old Shostakovich immediately volunteered for the army, but with his eyesight – to say nothing of his importance as a cultural icon – he was instantly rejected, being told:

“We’ll call you when we need you.”

He spent the next month digging ditches and anti-tank barriers around Leningrad and was then assigned to the Conservatory firefighting brigade. But mostly, Shostakovich composed, with an intensity new even for him. He arranged patriotic melodies and anthems, composed marching songs and, most importantly, continued work on his Symphony No. 7, working so intensely that he often took the score with him to the roof of the Conservatory where he was assigned to fire duty. He later recalled:

“I wrote my Seventh Symphony, the Leningrad, quickly. I couldn’t not write it. War was all around. I had to be together with the people, I wanted to create the image of our embattled country, to engrave it in music.”

Shostakovich completed the monumental first movement of the Seventh on September 3, 1941, just as the Germans were completing their blockade of Leningrad.

By early September of 1941, most of Leningrad’s artists and intellectuals had been evacuated from the city. For his part, Shostakovich refused to evacuate. On September 4, the Germans began shelling Leningrad. Two weeks later, on September 17, Shostakovich broadcast the following over Leningrad Radio:

“An hour ago I finished the score of the second movement of a large symphonic composition. If I succeed in carrying it off, if I manage to complete the third and fourth movements, then perhaps I’ll be able to call it my Seventh Symphony. Why am I telling you this? So that the radio listeners who are listening to me now will know that life in our city [goes on].”

Two weeks later Shostakovich was ordered to evacuate and, to the gigantic relief of his friends and family (to say nothing for posterity), he flew out of Leningrad with his wife and two children on October 1, 1941.

Eventually, Shostakovich and his family ended up in an artist colony in Kuybishev, on the Volga River just west of the Ural Mountains. It was there that Shostakovich completed his Seventh Symphony on December 27, 1941.

Shostakovich and his Seventh Symphony were propaganda manna from heaven for the embattled Soviet government. Here was the heroic young composer, resisting evacuation from his native city, at the same time composing a symphony that would express the plight, the power, the dignity and the determination of the Soviet people. Is there a publicist anywhere who couldn’t work with that? Shostakovich and his Seventh Symphony became symbols overnight. On July 20, 1942 he appeared on the cover of Time magazine wearing his fireman’s helmet. Meanwhile, the finished score of the Seventh was carried out of Russia on microfilm, to be performed and broadcast across England and the United States.

The score and parts for the symphony were then flown back into Leningrad for a gut-wrenching performance in that besieged city on August 9, 1942 by the starving members of the Leningrad Radio Orchestra, conducted by Karl Eliasberg. Loudspeakers broadcast the performance throughout the city as well as to the German troops in their siege-lines just outside of the city. According to Shostakovich biographer Laurel Fay:

“The Seventh anchored itself in the popular consciousness as an instantaneous cultural icon, something totally unprecedented for a serious symphonic work.”

The playwright Alexander Kron summed up the Leningrader’s own reaction to the symphony:

“People who no longer knew how to shed tears of sorrow and misery now cried for sheer joy.”

(It is a story well told in M. T. Anderson’s Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad, Candlewick Press, 2015.)

It is no understatement to say that Shostakovich and his Seventh Symphony became the stuff of legend.

The truth – the real meaning of the Seventh Symphony – is even more interesting than legend.

Shostakovich played through the completed Seventh Symphony for his friends and neighbors in Kuybyshev on the evening of December 27, 1941. Later that same evening he got into a conversation with Flora Litvinova, a neighbor and friend of his wife. Litvinova recalled:

“I looked in on the Shostakovichs. They were talking about the symphony. And then Dmitri Dmitriyevich said reflectively: ‘the symphony is about Fascism, of course. But Fascism isn’t simply [Nazism]. The music is about terror, slavery, the bondage of the human spirit.’ Later, when Dmitri Dmitriyevich began to trust me, he told me directly that the Seventh (and the Fifth as well) are not about fascism but about our system, in general about totalitarianism.”

Shostakovich purportedly said much the same thing some 30 years later:

“The Seventh Symphony had been planned before the war and consequently it simply cannot be seen as a reaction to Hitler’s attack.

Naturally, fascism is repugnant to me, but not only German fascism; any form is repugnant. Nowadays people like to recall the prewar period as an idyllic time, saying that everything was fine until Hitler bothered us. Hitler is a criminal, that’s clear, but so was Stalin.

I feel eternal pain for those who were killed by Hitler, but I feel no less pain for those killed on Stalin’s orders. I suffer for everyone who was tortured, shot, or starved to death. There were millions of them in our country before the war with Hitler began.

The war brought much new sorrow and much new destruction, but I haven’t forgotten the terrible prewar years. That is what all my symphonies, beginning with the fourth, are about, including the Seventh and Eighth.

Actually, I have nothing against calling the Seventh the Leningrad Symphony, but it’s not about Leningrad under siege, it’s about the Leningrad that Stalin destroyed and that Hitler merely finished off.

The majority of my symphonies are tombstones.”

That last quote comes from a book entitled Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, as related to and edited by Solomon Volkov, Harper and Row, 1979. It is a controversial book, and because of that controversy, I generally do not use it as a primary source. But use it I do. The controversy surrounding Testimony is fascinating, and it’s a story that will be told in next week’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post, which will be published on July 28 on Patreon.

Again, stay tuned!

For lots more on the life and music of Dmitri Shostakovich, I would direct your attention to my Teaching Company/Great Courses survey, entitled (oddly enough) The Life and Music of Dmitri Shostakovich.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More