On March 4, 1678 – 341 years ago today – the Italian composer, violinist, priest and rapscallion Antonio Vivaldi was born in Venice. Yes, I know we are all “one-of-a-kind” and that that phrase is way overworked, but truly, Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was a genre unto himself!

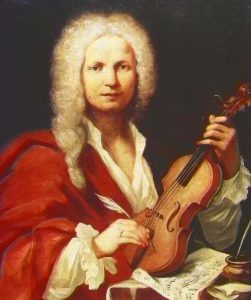

Vivaldi came to be known il prieto rosso (“The Red Priest”) for two excellent reasons: he had bright red hair and was trained as a Catholic priest. He might just as easily – and accurately – have been called “The Red Violinist” or Il Rosso Compositore: “The Red Composer”.

All together, Vivaldi composed 49 “serious operas” in the ornate Venetian style that was all the international rage at the time. For better or for worse, the great bulk of these operas have fallen into obscurity; their artificial story lines and formulaic construction don’t resonate well with modern audiences. However, Verdi’s concerti do indeed resonate, and there are a lot of them: over five hundred in number. (49 operas. 500-plus concerti. Add to that hundreds upon hundreds of sacred works. These are crazy numbers, and despite the formulaic construction of much of this music, we must stand in awe of Vivaldi’s amazing fecundity. Let’s hear it for living in an age without electronic distractions!)

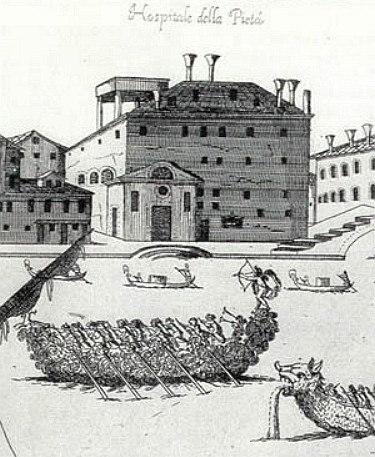

Just under half of Vivaldi’s concerti – roughly 230 of them – are for solo violin and orchestra. Modern scholarship has confirmed that virtually all of them were written for performance at a Venetian convent-slash-orphanage-slash-conservatory of music called the Pio Ospedale

Ah, Venice!

The city of Venice was not just – once upon a time – the capital of a maritime empire and one of the wealthiest and most populous cities in Europe. It was (and remains) a work of art; an urban theme park that to this day induces visitors to shake their heads in disbelief. The city is built in the middle of a shallow lagoon on 118 tiny islands. It is crisscrossed by 177canals and connected by 409 bridges. For hundreds of years Venice has been a necessary destination, an essential stop on everyone’s “grand tour”.

At the time of Vivaldi’s birth – in 1678 – Venice was the most decadent, licentious, anything-goes city in the Western world. With its many opera houses and theaters; its Carnival season; its world-famous casinos and prostitutes, Venice was the Las Vegas of the seventeenth century: hey baby, what happened in Venice stayed in Venice!

In a seaport city and destination like Venice, filled with sailors and tourists and prostitutes, what often “happened in Venice” was unwanted children. Thus, the presence in Venice of four orphanages for girls: the Pietà, the Incurabili, the Mendicanti, and the Ospedaletto. These facilities dated back to the crusades, when they were opened as hostels (in Italian, ospidali) for pilgrims. By Vivaldi’s time they had become orphanages for foundling girls: infant girls abandoned by their mothers and left in a “baby hatch” (or what was called a “foundling wheel”) in the wall of an orphanage.

The girls in these orphanages were educated and taught trades, and no trade was more important in Venice than music. By the seventeenth century, these orphanages operated the city’s most important conservatories of music, where the standards were so high that the nobility enrolled their own daughters in them for study. By Vivaldi’s time, the orphanages had become a center of Venetian musical activity.

Writing in 1739, the travel writer Charles de Brosses – the Rick Steves of his day – described the concert scene in Venice this way:

“A transcending music here is that of the hospitals. There are four of them, made up of bastard or orphaned girls. They are trained solely to excel in music. And so they sing like angels and play the violin, the flute, the organ, the ‘cello, and the bassoon; no instrument frightens them. They are cloistered in the manner of nuns. They perform, and each concert is given by about forty girls. I swear to you that nothing is so charming as to see a young and pretty nun in her white robe, with a bouquet of pomegranate flowers over her ear, leading the orchestra with all the grace and precision imaginable.

The hospital I most often go to is that of the Pietà, where one is best entertained.”

Yes: the most highly regarded of Venice’s four orphanage conservatories was the Pietà. It had been founded in 1346 and was situated on the Riva

On the bottom

Antonia Vivaldi: Up Close and Personal

Vivaldi was a flashy, egomaniacal-bordering-on-megalomaniacal, unscrupulous, thin-skinned, greedy wheeler-dealer who lied outrageously whenever he felt like it. Having said that, he worked like a dog (like most musicians); he was always scraping for money (like most musicians); and was compelled by the nature of his career to write more music in a month than many composers did in a year.

A priest as well as a musician by profession, Vivaldi’s sex life was active and varied, a sex life that was an object of commentary and fascination by his contemporaries. And while Vivaldi was neither the first – nor last – man of the cloth to indulge the flesh, his flamboyance and visibility assured that his actions created a scandal. Just how he managed to avoid being defrocked remains anyone’s guess.

According to the Vivaldi scholar John Talbot:

“Antonio Vivaldi was so unconventional as both man and musician that he was bound to elicit much adverse comment in his lifetime. His vanity was notorious: he boasted constantly of his fame and of his illustrious patrons, and of his fluency in composing, asserting that he could compose a concerto in all its parts more quickly than it could be copied. In many cases these claims are clearly exaggerated. Along with his vanity went an extreme sensitivity to criticism. His preoccupation with money was excessive by any standards; it is a subject that surfaces continually in his letters. Yet the sheer zest of the man compelled admiration.”

He was born on March 4, 1678 in Venice, which was then the capital city of “Serenissima Republicca di Venezia, or the “Most Serene Republic of Venice”, an independent state that consisted of a good portion of what today is northern Italy, the coastlines of Croatia, Albania, and Greece, and various islands in the Adriatic Sea.

Vivaldi’s poppa – Giovanni Battista Vivaldi – was a professional violinist who taught his son Antonio well. Little Antonio exhibited remarkable precocity as both a violinist and as a composer. However, as the eldest son of a poor household, it was expected that he would join the priesthood. And this he did, receiving the first of the so-called minor orders, that of Ostario (“Porter”), on September 19, 1693 at the age of fifteen.

Vivaldi was certainly not the first man of his time to combine a musical career with that of the priesthood, although in Vivaldi’s case the priesthood came a distant second. While he was ordained a priest in March of 1703, chronic asthma precluded him from being able to say Mass. So “handicapped”, he joined the faculty of the Pietà as maestro di violino (“master of the violin”) in September of 1703, and thus began a relationship that would continue for the next 37 years.

About a year after Vivaldi took up his position at the Pietà, the Venetian publishing house of Sala issued a set of trio sonatas – works for two violins, cello, and a chord-playing instrument – as Vivaldi’s Opus 1. A series of major publications followed. His set of 12 concerti published as Opus 3 in 1711 by the house of Etienne Roger in Amsterdam under the title L’estro armonico (usually defined as “Harmonic inspiration”) is generally considered to be the single most influential music publication of the first half of the eighteenth century. (That is not an overstatement. Roughly 340 miles to the north, the court organist in the Saxon city of Weimar – a young dude named Johann Sebastian Bach – read through Vivaldi’s Op. 3 concerti and was so taken by what he heard that he arranged two of them for solo harpsichord, three of them for solo organ, and one of them for four harpsichords and orchestra. By doing so, Bach absorbed Vivaldi’s compositional style the way the blobabsorbed all those people in the movie theater and made it his own.)

In May of 1713, Vivaldi’s first opera – entitled Ottone in Villa – was produced in the northern Italian city of Vicenza, just inland of Venice. Such was its success that Vivaldi began composing and producing operas in Venice itself.

By 1718, the 40-year-old Vivaldi’s music had gone viral. Gigs in Mantua, Rome, Vienna, Verona, Ancona, Ferrara, and Trieste followed while, at the same time, Vivaldi continued to compose concerti for the Pietà. These were Vivaldi’s “salad days”, during which he rubbed shoulders with some of the mightiest aristocrats of his time and made a lot of money.

Fame and fortune; Vivaldi had it all. Unfortunately, few things are more fleeting than fame, and fortune – in the hands of a wastrel like Vivaldi – can disappear in the blink of an eye. In 1741, the 63-year-old Vivaldi, having fallen out of popular favor and gone bankrupt in Venice, decided to revive his flagging fortunes in Vienna. It was, as it turned out, not a good idea. On July 28, 1741 a month to the day after having arrived in Vienna, Vivaldi died. The cause of death was listed as “internal inflammation”, which could have been anything, including a broken heart.

Vivaldi was buried in the cemetery of the public hospital, a facility called the Bürgerspital-Gottesackers, just outside the city walls near the present-day Karlskirche. At his last rites, six choirboys from St. Stephens Cathedral sang a Requiem Mass, one of who was the 9-year-old Joseph Haydn. Some years after Vivaldi’s death the cemetery was abandoned and built over, and as a

Back in Venice, Vivaldi’s obituary, written by Pietro Gradenigo, concluded this way:

“[So we mark the death of] Abbé Lord Antonio Vivaldi, incomparable virtuoso on the violin, known as the red priest, much esteemed for his compositions and concertos, who earned more than 50,000 ducats in his life, but his disorderly prodigality caused him to die a pauper in Vienna.”

An unfortunate epitaph!

Nevertheless, happy 341st, baby!

For lots more on Vivaldi, I would direct your attention to my examination of The Four Seasons in my Great Courses survey The 30 Greatest Orchestral Works.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More