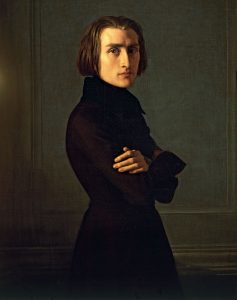

159 years ago today, on November 7, 1857, Franz Liszt’s Dante Symphony for orchestra and female choir received its premiere at the Royal Theater in the Saxon capital of Dresden. The 46 year-old Liszt was, at the time, the most famous and beloved performing musician in all of Europe, and nowhere was he more popular than in Dresden, where he was considered something of a second son by the locals. Alas, Liszt’s popularity in Dresden did him no good; the premiere performance of his Dante Symphony was a fiasco and Liszt was all but hissed off the stage. The disaster was attributable to one thing: Liszt’s failure to take his own advice.

159 years ago today, on November 7, 1857, Franz Liszt’s Dante Symphony for orchestra and female choir received its premiere at the Royal Theater in the Saxon capital of Dresden. The 46 year-old Liszt was, at the time, the most famous and beloved performing musician in all of Europe, and nowhere was he more popular than in Dresden, where he was considered something of a second son by the locals. Alas, Liszt’s popularity in Dresden did him no good; the premiere performance of his Dante Symphony was a fiasco and Liszt was all but hissed off the stage. The disaster was attributable to one thing: Liszt’s failure to take his own advice.

Advice. Along with talking politics, religion, and dangling our feet in piranha-infested rivers, few things are more fraught with danger than giving (or receiving) advice.

Yes: on occasion, we will solicit advice, and sometimes we’ll even follow that advice (provided that it corresponds with what we were going to do in the first place). But as often as not we receive (or give) advice that was neither asked for (unsolicited advice) nor desired (well-intended advice), advice that can cause no end of bad feelings between advisor and advisee. And then there’s “parental advice”, a particularly irritating type that must be rejected instantly lest its giver feel empowered to offer up more of same.

To my mind, the most potentially useful advice is the advice we give to ourselves. Such advice is usually a product of personal experience: we mess up and say to ourselves something on the lines of: “I strongly advise you not to do that/go out with her (him)/behave that way/drink that much again.” Such advice goes under the heading of good advice.

In 1856, Franz Liszt published a collection of Symphonic Poems, a Symphonic Poem being a one-movement orchestra work that “tells” a literary story. Liszt came to composing orchestral music rather late in his life, having spent the first half of his career fashioning himself into not just the greatest pianist of his time but very possibly the greatest pianist who has ever lived. When Liszt did begin composing orchestral music – when he was in his late thirties – he transferred his astonishing virtuosity as a pianist and as a composer for the piano to the orchestra. The result was a body of complex, idiosyncratic orchestral music that was very difficult to play.

So back to the collection of symphonic poems Liszt published in 1856. The collection included a preface, in which Liszt insisted that the works therein not be performed without adequate preparation, meaning lots and lots of rehearsal time. Good advice, useful advice, yes? Yes. It’s advice that Liszt should have followed himself just a year later, in 1857.

After two years of work, Liszt finished his Dante Symphony – which is based on Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy – in the early autumn of 1857. The Symphony is cast in two movements. The first movement, entitled “Inferno”, traces Dante and Virgil’s passage through the nine Circles of Hell. (A modern version would take place at the DMV. Trust me on this; I’ve just had to renew my driver’s license.) The second movement, entitled “Purgatorio”, depicts Dante and Virgil’s ascent up the Mount of Purgatory. Following the tripartite structure of Dante’s Inferno, Liszt had originally planned a third movement entitled “Paradiso”: Paradise. However, the dedicatee of the Symphony and Liszt’s future son-in-law, the extraordinary and extraordinarily irksome Richard Wagner, talked him out of composing that third movement, telling Liszt that “no earthly composer could faithfully express the joys of Paradise.” Convinced by Wagner’s argument (did anyone ever disagree with Wagner in his presence?), Liszt concluded “Purgatorio” with a Magnificat, a text also-known-as the “Canticle of Mary”, a text that promises the coming of Paradise for the faithful. In order to sing the Magnificat at the conclusion of the Symphony Liszt added a female “choir of angels” which, as per his instructions, was to perform from a gallery above or near the stage.

Liszt’s Dante Symphony is a particularly challenging work, replete with some really outlandish harmonic experiments, unusual time signatures and key areas, constantly changing tempi (speeds) and chamber music-like interludes. Anxious (over-anxious!) to hear it performed, Liszt jumped at the chance to conduct the premiere of Symphony at the über-prestigious Hoftheater (the Royal Theater) in Dresden. The good news? They loved Liszt in Dresden and the orchestra of the Royal Theater was among the very best in Europe. The bad news? The Dante Symphony was to be allotted just ONE REHEARSAL.

What was Liszt thinking? What was Liszt smoking/drinking/snorting? Everyone advised Liszt against it, including Liszt’s (present) son-in-law, the brilliant pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow. But Liszt took no one’s advise, including his own, and the premiere “performance” (“performance” being something of a euphemism here) was a total disaster, the single most humiliating experience of Liszt’s long and storied musical career. Ouchie.

To quote/paraphrase that great moralist Yogi Berra, when you come to a fork in the road – or get good advice – you take it. Never stint on rehearsal time. Never. Ever. Not even if you are Franz Liszt.