9-11; a somber day for us all. A day for reflection, contemplation and yes, a day to grieve.

Far more often than not, this post is about celebration: celebrating the life of a musician or some great (or small) event in music history. If we chose to, we could celebrate the lives and music of two wonderful composers today. The great French composer and harpsichordist François Couperin died in Paris, at the age of 65, 284 years ago today, on September 11, 1733. The wonderful Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt was born 82 years ago today, on September 11, 1935.

However, I’ve chosen, today, not to celebrate but rather, to observe some particular deaths: stupid deaths, unnecessary and premature deaths. A grim topic but not an uninteresting one, given that death is one of the very few things each of us will eventually have in common.

The cue for today’s post was the birth, 104 years ago today, of Betty Stone in Norwich, Connecticut. Ms. Stone was an alto and a member of the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera. We read from an article that appeared on page 44 of the New York Times on May 2, 1977:

“CLEVELAND, May 1—A member of the chorus of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Company was killed here last night when her flowing costume was caught in the grille of a backstage elevator.

The accident occurred just after the curtain went down on the second act of II Trovatore, the final opera of the Met’s one-week stay in Public Hall. Backstage, some cast members walked upstairs to the dressing rooms, while others lined up for the half-century-old elevator.

Betty Stone, 63 years old, in the Met chorus since 1945, was the last to squeeze into the 8‐by‐6 elevator.

The robe she wore as a nun in the cloister scene caught in the door and, as the elevator rose, Miss Stone was dragged to the floor. ‘Oh, my God! Oh, my God!,’ the elevator operator, Norman Reser, heard someone shout. He stopped the elevator, but Miss Stone, dragged down as the cage went up, had caught her head between the side of the shaft and the elevator.

Frank M. Duman, a member of the. Public Auditorium Commission in Cleveland, said the elevator was to have gone out of service [that] night as part of a remodeling of old sections of the building. It had been scheduled to he used for only another hour.”

That’s just awful. And stupid. Singing in an opera chorus she not be hazardous to your health. Happy birthday, Betty Stone; you no doubt deserved better.

In the spirit of “misery loves company”, I would offer up a few other egregiously stupid musician deaths.

We would mark the death, on March 29, 1888, of the 74 year-old Charles Henri Valentin Morhange (best known as “Alkan”). A superb pianist, considered – in his prime – to be the equal of Chopin and Liszt, Alkan wrote piano music that was so difficult it was considered unplayable even by the excessive virtuosic standards of the nineteenth century. One reason he is so little known today (aside from the transcendental difficulty of much of his music) is that as he got older he got stranger and meaner, becoming by his mid-40s a virtual recluse who rarely left his apartment. For years the story circulated that he had been killed by a falling bookcase. A practicing orthodox Jew, Alkan – so the story went – was reaching for a Hebrew religious book when the entire bookcase fell on him and crushed him to death. In fact, the real story is even stupider. He was in his kitchen when he either slipped or fainted. As he fell, he grabbed at a porte-parapluie (a heavy coat/umbrella rack), which came down on top of him. Found moaning under the porte-parapluie by his concierge, he was carried to his bedroom where he died a few hours later. Death by umbrella stand. How lame.

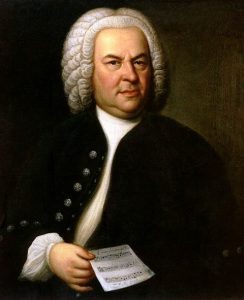

We would mark the death of our beloved Johann Sebastian Bach at the age of 65 due to a medical malpractice nightmare. Bach’s eyesight had been poor for many years, partly due to the endless strain of writing and copying music late at night in near darkness, but very likely also due to diabetes. By 1749, at age 64, he was nearly blind. Enter one “Chevalier” John Taylor, an English “oculist” traveling through Germany who reportedly was performing “amazing eye operations.” Bach entrusted himself to Taylor, who performed two disastrously unsanitary operations on Bach, both failures. Afterwards, Bach’s doctor reported that Bach suffered “accidental inflammation.” Infection set in, then a stroke, then a horrific fever; Bach died on July 28, 1750, surrounded by his family.

(For our information, this same quack doctor John Taylor conducted cataract surgery on George Frederic Handel in 1751, permanently blinding him.)

Infection and more infection. A handful of antibiotics would have saved the lives of countless millions, including Schubert, Schumann, Smetana, Mahler and Alban Berg. The death of Berg, the great German expressionist composer, is a particularly sorry tale.

Just a couple of days after he finished his brilliant Violin Concerto on August 11, 1935, Berg was stung on his lower back by what was likely a wasp, to which he was allergic. First a carbuncle, then a boil developed, followed by a nasty abscess. Berg’s wife Helene reportedly lanced it with a pair of scissors, and whether it was the abscess itself or Helene Berg’s likely less-than-sanitary outpatient surgery, Berg developed general septicemia from which, before antibiotics, there was little chance of recovery. Surgery and a blood transfusion followed, but to no avail. Berg died on December 24, 1935, age 50 years and 11 months, never having heard a performance of his Violin Concerto.

Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern grieved mightily over their friend Alban Berg. Sadly, Webern was to die ten years later under circumstances even more ridiculous than those of Berg.

Webern’s music was banned by the Nazis as being Entartete Kunst, “degenerate art.” A native of Austria, he kept a very low profile and managed to survive World War Two. As the war drew to its close, Webern, his wife, daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren took up residence in the Austrian alpine town of Mittersill, believing it to be a safe place to wait out the chaotic days following the end of the war. There in Mittersill, Webern’s son-in-law Benno Mattel – a former member of the SS – got himself involved in the post-War black market. On the evening of September 15, 1945, the American authorities organized a sting operation and arrested Mattel at the house in which the entire family had just finished eating dinner. At exactly the moment the arrest was taking place in the kitchen, Webern – completely unaware that a sting operation was taking place just a few feet away – walked out of a bedroom and stepped outside the house, there to smoke a cigar. Hearing the door close, one of the American soldiers involved in the sting, Pfc. Raymond Norwood Bell – a company cook from North Carolina – went outside to investigate. Bell bumped into Webern, panicked, and shot him three times. By the time medical help arrived, Webern was dead.

Ten years later, on September 3, 1955 Raymond Norwood Bell died of acute alcoholism. According to his wife, a schoolteacher named Helen Bell, her husband’s alcoholism was a result of the guilt he felt over Webern’s death.

More evidence – not that we needed it – that smoking kills.