We mark the birth on May 11, 1888 – 132 years ago today – of the Russian-born American songwriter Irving Berlin (1888-1989). Berlin wrote the words and music to over 1500 songs across a 60-plus year career. He is an American institution, whose life was, according to his obituary in the New York Times, “a classic rags-to-riches story that he never forgot could have happened only in America.” Having emigrated from his native Russian Empire at the age of five, Berlin grew up dirt poor in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Nevertheless, he was a legend by the age of 23. All told, he wrote the scores for 20 Broadway musicals and 15 Hollywood movie musicals. His songs were nominated for eight Academy Awards. (His one Oscar win came in 1943, for the song White Christmas. Bing Crosby’s recording has sold upwards of 100 million copies, and remains the best-selling single of all time).

A word. I have been writing these Music History Monday posts since Monday, September 5, 2016. Over the years, these posts have run between 1500 and 2000 words; a few shorter and a very few longer. (I figure if you can’t tell a good story in 2000 words, you shouldn’t be telling it at all. For our reference, Op-Ed columns in the New York Times run between 400 and 1200 words, with 650 words considered the “sweet spot”.)

But for the first time in these Music History Monday posts, I am not going to exercise my usual editorial restraint regarding word count; Irving Berlin and his songs are just too important and, I believe, presently underappreciated to short-sell them. So here is what we’re going to do. Today’s Music History Monday post (which runs over 2600 words), will discuss the nature of Irving Berlin’s songs; their importance to the twentieth century American experience; and Berlin’s early life up to the publication of his first song, Marie from Sunny Italy in 1907. Tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post, which will appear at Patreon.com/RobertGreenbergMusic, will pick up Berlin’s biography in 1907 and take it through 1911, when he created the song that made him a legend: Alexander’s Ragtime Band. From there we’ll discuss his amazing, truly singular output, paying particular attention to his skills as a lyricist. (No offense intended to the great Robert Zimmerman – a.k.a. Bob Dylan – but if any American songwriter deserves to win a Nobel Prize in literature, it is Irving Berlin.) Tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post will conclude with three recommended CDs, discs that I believe best demonstrate the singular range and substance of Irving Berlin’s songs, a recommended biography, and links to couple of excellent online videos.

(I know, I know: Patreon is a subscription site which, heaven forbid, costs $2, or $5, or $10 or more per month – depending upon your largesse – to subscribe to. But I am presently posting on Patreon 4 to 5 times a week, and these subscription $’s are providing me with the time and financial wherewithal to be able to create vlogs and blogs, including Music History Monday. So please consider subscribing!)

I will happily admit that when it comes to Irving Berlin, there are personal issues involved. Berlin the person and his songs were a constant presence in my life growing up, one of the five killer bees that shaped my musical consciousness: Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, the Beatles, and Berlin (and, I will also admit, one killer “G”: Gershwin). The events of Berlin’s early life mirror those of my own family; his family emigrated from what today is Belarus as did both sides of mine; he grew up in the same neighborhood as my grandparents; my paternal grandfather Sidney Greenberg (1891-1973) – three years younger than Berlin – claimed to have known the young Berlin personally and to have seen him perform many times.

From the youngest age (very likely pre-natal, even), Berlin’s songs were drummed into my head. My maternal grandmother (Sidney’s wife, Bessie, 1894-1971), was a New York Institute of Musical Art/Juilliard trained pianist who, having decided that my father (Alvin Greenberg, 1925-2017) was going to be “the next Paderewski”, tortured him with piano lessons and a 4-hour a day practice regimen throughout his childhood. (I used the word “torture” because that’s the word my father used in describing his childhood routine.) He did indeed become a very good piano player, but (wisely) never took it seriously as a career path and when he left the Navy after World War Two, he went into business.

But this doesn’t mean that my father stopped playing the piano. Parties at our house inevitably devolved into sing-a-longs with my father at the piano, and pretty much every night after dinner he’d sit down and play. Sometimes it was music composed by dead Germans and Austrians, but far more often it was songs from the so-called “Great American Songbook”: the popular American songs of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway and movie musicals. The songs of George and Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, and Irving Berlin.

To my ears, Berlin’s songs always stood apart from the others. They don’t generally exhibit the slick, jazz-inspired veneer of Gershwin’s and Rodgers (and Hart’s) songs; or the sophisticated, urban shtick of Porter’s and Kern’s songs; or the compositional virtuosity of any of the above.

(Regarding compositionally virtuosity: Berlin never learned to read or write music. He hired a succession of “musical secretaries” to notate his songs, which he sang to them while accompanying himself on the piano. And regarding Berlin’s piano playing: he was self-taught and able to play in only one key: F-sharp. Early on he acquired a so-called transposing piano that by pulling a lever sounded in different keys despite the fact that he was still playing in F-sharp. Berlin demonstrates his piano to Dinah Shore and Tony Martin in the linked video:)

What sets Berlin’s songs apart is their incredible directness and naturalness: like the songs of Stephen Foster, like folk songs, like religious hymns, Berlin’s songs seem always to have existed, so perfectly matched are their words and music, so unaffected and clear are their expressive content. No small part of this is due to the fact that Berlin, unlike any of the other great Tin Pan Alley songwriters, came to writing songs as a singer and not as a piano player. As a singer, he always preferred to use the most direct, most “singable” melodies he could create, and words he could find. As a songwriter, he never valued literary “flash” at the expense of clarity, and as such, his songs have a colloquial, “every person” sensibility, giving them an almost universal appeal. This is why, for example, Berlin’s song Blue Skies, which was written in 1926 for a Broadway musical called Betsy, could be recorded by Willie Nelson more than fifty years later to become the #1 country music hit of 1978.

Berlin’s great contemporaries were of a single mind when it came to him and his songs. George Gershwin (1898-1937) called Berlin “the greatest American song composer, America’s Franz Schubert.” Cole Porter (1891-1964) took things a step further, calling Berlin “the greatest songwriter of all time.” Jerome Kern (1885-1945) was once asked to “place” Berlin within the larger panorama of American music. His response: “Irving Berlin has no ‘place’ in American music – Irving Berlin IS American music.”

The America composer, educator, and author Douglas Stuart Moore (1893 – 1969) acknowledged Berlin as something much more than just a “songwriter”, setting him beside Stephen Foster, Walt Whitman, and Carl Sandburg as “a great American minstrel [someone who has] caught and immortalized in his songs what we say, what we think about, and what we believe.”

He was born Israel Isidore Beilin on May 11, 1888, the youngest of eight children born to Lena Lipkin (1850-1922) and Moses Beilin (1848-1901). The family came from a shtetl named Tolochin in today’s Belorus, although documents say that Berlin was born in Tyumen, Siberia, some 1600 miles east of Moscow. His father was an itinerant cantor, which probably explains the family’s temporary presence in Siberia.

At the time of Berlin’s birth, the Russian Empire was a particularly unfriendly place for Jews. The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in St. Petersburg on March 13, 1881 triggered a devastating series of restrictive laws and pogroms against Russia’s Jewish population, despite the fact that that population had virtually nothing to do with the Tsar’s assassination. (What else is new? When in doubt, despots blame/scapegoat those least able to defend themselves.)

Due to these pogroms, my great-grandparents left their shtetl outside of Pinsk in today’s Belarus circa 1886 and made their way to New York City. Some seven years later, Moses Beilin likewise found it necessary to uproot his family. Irving Berlin told to his first biographer Alexander Woollcott that his earliest memory, according to Woollcott, “was of lying with the rest of the family beside a road, wrapped in a blanket, watching as his home and village were burned in a pogrom.”

The family trudged across Europe, boarded the S.S. Rhynland in Antwerp, and sailed for the presumably gold-paved streets of America. After a journey of 11 days, the Rhynland sailed into New York Harbor and past the Statue of Liberty, inscribed on the base of which are Emma Lazarus’ still magnificent, still gut-wrenching, awe-inspiring, and weep-inducing words:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

After passing through the newly opened immigration facility on Ellis Island (where the family name was respelled as “Baline”), the family took the ferry to Manhattan. Berlin remembered:

“We spoke only Yiddish and were conspicuous in our ‘Jew clothes’”.

The family settled in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which the Nobel Prize winning author Rudyard Kipling described as being “worse than the slums of Bombay.”

After a brief stay in a cellar on Monroe Street, the Baline family occupied a three-room tenement at 330 Cherry Street, which is where young “Izzy” grew up.

Berlin’s father Moses couldn’t find work as a cantor, so he took a job at a Kosher meat market and gave Hebrew lessons on the side. His mother worked as a midwife; his brother in a sweatshop, and his sisters rolled cigars. Berlin himself hawked newspapers in the Bowery, all the while singing songs he heard coming out of the saloons and restaurants that lined the busy streets. He had a clear, clean singing voice and he liked to make up new words as he sang, and soon enough people began tossing coins at him. So began his career as a professional musician!

When Moses Baline died in 1901, the 13-year-old Izzy left school for good and became an itinerant street singer. Over time, he learned that his audiences preferred song lyrics that described simple, every-day sentiments set to direct and memorable melodies.

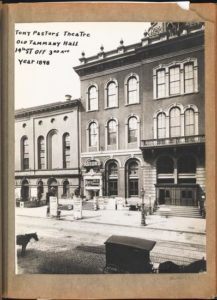

At the age of 16 (or thereabout), Berlin was hired to be a “singing stooge” for $5.00 a week at Tony Pastor’s Music Hall at Union Square. (Explains Berlin biographer Philip Furia, “when a performer sang a song from the stage, the “stooge”, planted in the back of the audience, would rise and, as if spontaneously carried away by the song’s beauty, lead the audience in chorus after chorus.” It was thanks to such stooges that audience members would not leave a theater without having bought the sheet music for the songs they just sang, thus guaranteeing that the song would “circulate.”)

It was at Tony Pastor’s that the variety show entertainment known as “vaudeville” was born. Berlin worked there as a stooge for a “family act” called “The Three Keatons”. The Keatons all sang; additionally, “Pa” told jokes, “Ma” played the saxophone, and young “Buster” Keaton did acrobatics, the likes of which would help make him one of the most popular comedians of the silent film era.

In 1906, at the age of 18, Berlin got the job he considered, at the time, to be his dream job: that of a singing waiter at the Pelham Café at #12 Pell Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown. He was paid $7 a week plus tips. When the house piano player, “Professor” Mike “Nick” Nicholson struck up a tune, it was Berlin’s job to sing along. A fellow employee named Jubal Sweet remembered Berlin in action:

“Like it was yesterday. I remember Oiving Berlin. Looked like a meal or two wouldn’t hurt him. Wasn’t strong and didn’t look like he could get away with a nickel or a dime that one of the other guys claimed. Now a singing waiter couldn’t be stooping over every time a coin hit the floor. Spoil the song like – see? No, he’d keep moving around easy, singing all the time, every time a nickel would drop he’d put his toe on it and kick it or nurse it to a certain spot. When he was done he had all the jack in a pile, see? Oiviung got to be pretty good at it. He had a neat flip of the ankle. Like you’d brush a speck offa table with your fingers.”

In 1907, Berlin wrote his first song in collaboration with the Pelham Café’s house pianist Nick Nicholson. Titled Marie from Sunny Italy, it is a stereotypical genre song, typical of its time. Nowhere in Berlin’s lyric are the vernacular phrases that will later give his songs such a powerful sense of the contemporary. Instead, the lyric leans like a drunken sailor on a lamppost on the tritest clichés: “the little birds” are “sweetly humming”, “the Summer moon is beaming” and “the little stars are gleaming.”

Nevertheless, the song found a publisher and was released on May 8, 1907, three days before Berlin’s 19th birthday. The song was a commercial loser and sold but a few copies; Berlin earned all of 37 cents in royalties. (However, we would observe that the song’s commercial failure make it a collector’s dream, the Holy Grail of sheet music collecting, a copy of which in decent condition will probably sell in the upper-five figures.) Flop that it was, Marie from Sunny Italy did indeed serve two excellent purposes. First, as an examination of the cover reveals, it names its lyricist not as “I. (as in Irving) Baline” but rather, as “I. Berlin.” For decades it was rumored that this was a printing error that once made, Berlin decided to stick with. But in fact, Berlin told his first biographer Alexander Woollcott that his friends in the Bowery had already Anglicized his name to “Berlin” in everyday conversation. The other most excellent purpose served by Marie from Sunny Italy is that having seen his name in print Berlin was hooked on songwriting.

We pick up the story in tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post, on Patreon. Until then, we wish you, our dear Oiving, the happiest of birthdays!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More