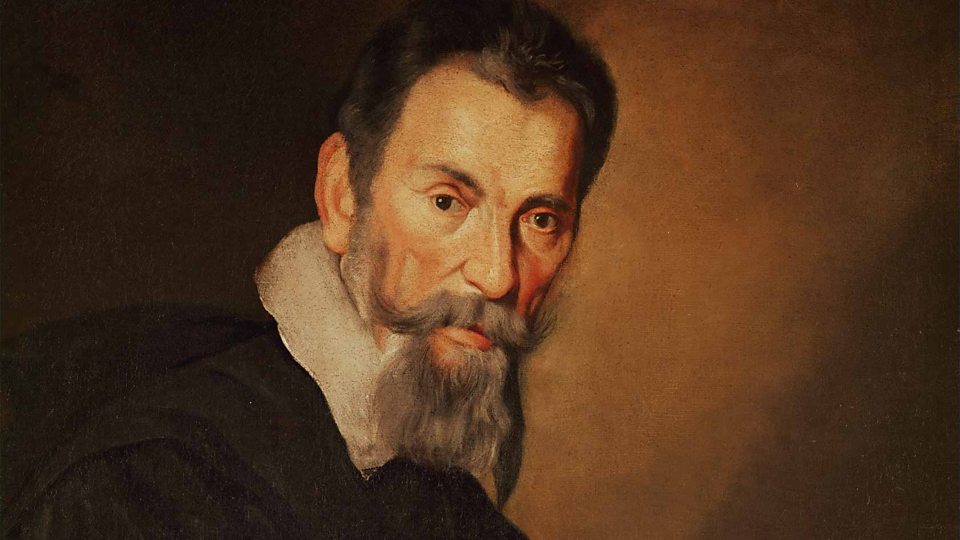

We mark the first performance on February 24, 1607 – 413 years ago today – of Claudio Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo, in Mantua, Italy.

I suppose I should apologize. I have been advised, gently but firmly, to diversify these Music History Monday posts as much as possible: to spread the topics around by focusing on relatively “contemporary musical events” (a euphemism for “popular musical events”) as well as on concert music and opera. And this I have done, as best as I can. For example, we celebrated the great Broadway composer Richard Rodgers on December 30; we discussed the fortunate/unfortunate patenting of the accordion on January 13; we dined on bat tartare together with Ozzy Osbourne on January 20.

Certainly, there is no shortage of (relatively) contemporary musical events we could celebrate here on February 24. For example, on February 24, 1965, the Beatles began filming the movie Help in the Bahamas. On February 24, 1978, “The Second Barry Manilow Special” was broadcast on ABC-TV with guest star Ray Charles (OMG; be still our hearts!).

On February 24, 1988 the delightful Alice Cooper (born 1948) announced he would run for Governor of the great state of Arizona as a member of the “Wild Party” (tragically, he was not elected). On February 24, 1992 Courtney Love (born 1964) married Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) on Waikiki Beach in Honolulu, Hawaii.

February 24, 1998 was an especially rich day in music history: Tommy Lee (born 1962; the drummer for and founding member of Mötley Crüe) was arrested and charged with assaulting his then-wife Pamela Anderson Lee (born 1967), for which he eventually served four months in jail; Elton John (born 1947) was knighted by QEII at Buckingham Palace; and Virgin Records America Inc. filed suit against the alternative rock band Smashing Pumpkins for alleged breach of contract and non-delivery of albums (imagine!).

Finally, on February 24, 1999, Johnny Rotten (born John Joseph Lydon in 1956) emceed VH1’s live Grammy coverage.

Wow.

Where do we start? Which of these ever-so-scintillating events do we choose to celebrate?

Not a single one of them. Because epoch-making though these incidents may have been (particularly, to my mind, Alice Cooper’s gubernatorial run), there is an event from the world of opera so seminal that it trumps them all, hands, feet, fingers, and toes down.

“Not another opera post!”, sputter my gentle but firm advisors. “Dude, this’ll be three opera posts in a row! C’mon, write about Barry, or Tommy and Pam, or Elton, or Alice, or Smashing Pumpkins!”

No can do, say I. Because the premiere of Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo in 1607 went a long way to changing life here on earth as we understand it, or at least music here on earth as we understand it which is, for me, pretty much the same thing.

Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo was the game changer, the single work that revealed that these newfangled “dramas with music” (which soon enough would come to be called “operas”) had the potential to be the transcendent Western art form, in which almost every one of the arts – music, drama, poetry, stage design (meaning architecture, painting and sculpture), costuming, and dance – combined into a whole a gazillion (or two) times greater than its parts.

Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo was the game changer because it is a first-order masterwork: the first great opera (and as such, the earliest opera that is regularly performed). As the first great opera, it demonstrated as nothing before it the awesome expressive potential of the art form.

A bit of background; indulge me.

That period of time we so blithely call the “Renaissance” (or “rebirth”; a term that was coined by the French Historian Jules Michelet in the 1860s) is understood as running in music between (roughly) 1400 and 1600. What was “reborn” during this hunk o’ time was an awareness of and appreciation for ancient (primarily ancient Greek) art, architecture, philosophy, literature, and drama. This rebirth was an inherently humanistic, inherently secular (non-religious), movement, as its inspiration – the ancient world – pre-dated Christianity.

By the late sixteenth century – the late 1500s – this ancient Greek-inspired fascination (“fetish” would not be too strong a word) for things human (as opposed to things divine) led to an astonishing flowering of dramatic art, in which the feelings of and relationships between individual people were explored and celebrated to a degree almost entirely new. (For our reference, Shakespeare’s plays were written between 1590 and 1612, at precisely the same time opera was being invented and first popularized among Italy’s ruling elites.)

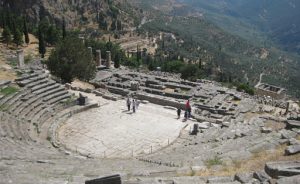

The inventors of opera were convinced that the ancient Greeks had sung (or at least chanted) their dramas, and that only this could account for the impact the Greeks themselves claimed their drama had on the human heart. Opera was born in Florence, Italy (as opposed to Florence Township, New Jersey, Exit 6A off the Turnpike) during the last years of the sixteenth century as an attempt, in modern guise, to recapture the dramatic art of the ancient Greeks. (For our information, the first surviving work that we today define as an opera is Jacopo Peri’s and Ottavio Rinuccini’s L’Euridice, which was first performed at the Pitti Palace in Florence on October 6, 1600. That first performance – and with it, the invention of opera – was discussed in my Music History Monday post of August 20, 2018.)

Early opera, like owning racehorses and sports teams today, was a rich person’s game. These so-called “court” operas were commissioned by wealthy aristocrats, to be staged as part of a major celebration: a wedding, a Christening, Carnival, a bar mitzvah; whatever. (For example, Peri and Rinuccini’s L’Euridicewas commissioned and performed for the marriage of King Henry IV of France and Maria de Medici.)

The life and job history of Maestro Claudio Monteverdi is described in some detail in my Music History Monday post for August 19, 2019. Fort now, we’d observe that the Cremona-born Monteverdi worked for Vincenzo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua, from 1590 until 1612, initially as a string player but starting in 1601, as the Duke’s maestro della musica (master of music).

In late 1606 or very early 1607, Monteverdi was tasked with composing his first opera, to be performed as part of the court of Mantua’s Carnival (pre-Lent) celebration. With words by the poet Alessandro Striggio, La favola d’Orfeo (“The Fable of Orpheus”) recounts (as did Peri’s L’Euridice) the story of the golden-throated Orpheus and his journey to the underworld in search of his snake-bitten nymph-squeeze Eurydice. What sets Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo apart from everything that preceded it and made it a model for the next four generations of composers is the manner in which Monteverdi synthesized recitative; rhymed, “pop”-styled songs and dances; madrigal choruses; and what was, at the time, a huge orchestra of some forty instruments into a singularly convincing, powerfully moving dramatic whole.

With Monteverdi’s 19 stage works in the lead (of which, tragically, only 6 have survived intact), opera became a public entertainment in Venice in 1637 and from there spread across Europe.

The overwhelming impact of opera on Western music and culture is not limited to the opera house itself, as the spin-offs from opera constitute a virtual “what’s what” in Western music over the last four centuries.

For example.

The “orchestra” as an instrumental entity owes its name and existence to opera. An “orchestra” is the circular or semi-circular area directly in front of the stage in a Greek theater, an area occupied by the Greek chorus during a play. The word was borrowed and applied to the instrumental ensemble that occupied that same space in an opera performance.

As opera houses grew bigger, so did the instrumental “orchestras” that accompanied those operas. The development in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of woodwind and brass instruments that could by tuned – like oboes, clarinets, bassoons and trumpets – was largely due to the demand for ever more instrumental color and effect in opera orchestras.

The development of the instrumental genre “concerto” in the 1680s and 1690s, which pits a solo instrument or group of solo instruments against the collective of the orchestra, grew directly out of operatic practice.

The multi-section orchestral overtures that preceded the performance of Italian-language operas evolved into the self-standing genre of “symphony” in the 1730s and 1740s.

The religious genres of oratorio and church cantata grew directly out of operatic practice and became, virtually, religious operas.

The tonal harmonic system was brought to its height of perfection in order to accompany recitative in the opera house. The small group of instruments that played those accompanimental harmonies – something called the “basso continuo” – became a universal element in Baroque era instrumental music.

Most importantly, the cultivation and depiction of individual emotions and individual emotional expression – of “feeling” – in both instrumental and vocal music can all be traced back to the invention of opera. And the invention of opera received its kick-start from Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo.

So: sorry Johnny Rotten. We’re sure you did a wonderful job emceeing VH1’s live Grammy coverage on February 24, 1999, a job worthy of notice and perhaps, even, praise. But in a head-to-head with Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, you lose, buddy. Consider it Rotten luck.

For lots more on the birth of opera and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses surveys How to Listen to and Understand Great Music and How to Listen to and Understand Great Opera, which can be examined and downloaded here at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More