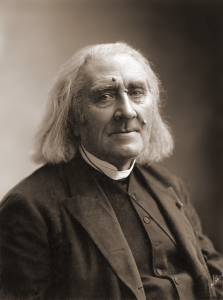

Party hats and noisemakers at the ready, today we celebrate the birth of Ferencz (that’s Hungarian; Franz in German) Liszt. (Woohoo! Let’s make some noise!) He was born on October 22, 1811 – 207 years ago today – in the market town of Doborján in the Kingdom of Hungary. (Today the town is known as Raiding and it is located in Austria.)

Here’s something we read/hear with tiresome frequency: “Like, yah, Mozart was the first ROCK STAR!”

No, he wasn’t. He was an intense, brilliantly schooled composer whose music was increasingly perceived by his Viennese audience as being too long and complex.

Okay; how about: “Beethoven was the first ROCK STAR!”

Oh please.

One more try. “Liszt was the first ROCK STAR!”

That he was. (Or perhaps the second, if we choose to consider Liszt’s inspiration, the violinist Niccolò Paganini to be the first true “rock star.”)

But: Paganini or no, in terms of Liszt’s looks and his fame, the tens-of-thousands of miles he travelled on tour and the thousands of concerts he gave; in terms of the utterly whacked-out degree of adulation he received, the crazed atmosphere of his concerts, and the number of ladies (and perhaps men as well) who would have joyfully welcomed him into their boudoirs, well, Liszt was indeed the prototype for the modern rock star, a composer and pianist who in his lifetime was worshipped as a secular god.

We read that:

“When Liszt played the piano, ladies flung their jewels on the stage instead of bouquets. They shrieked in ecstasy and sometimes fainted. Those who remained mobile made a mad rush to the stage to gaze upon the features of the divine man. They fought over the green gloves he purposely left on the piano. They fished out the stubs of cigars Liszt had smoked, while others came away from the concerts with priceless relics in the form of broken strings from the pianos he had played. These cigar butts and broken strings were mounted in frames and lockets and worshipped. Liszt did not give mere concerts; they were Saturnalia.”

“Saturnalia” indeed: they were events, happenings, mystical séances, orgies, rock concerts; they were Lisztomania (a contemporary term coined by Heinrich Heine to describe Liszt’s concerts).

But having said all of that, it was – in the end – Liszt’s piano playing that drove his audiences to almost mystical ecstasy. For example, in 1840, the great Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen heard Liszt perform in Hamburg. Andersen, an ordinarily clear-eyed observer of human nature and manners, was entirely swept away:

“He seemed to me a demon nailed fast to the instrument whence the tones streamed forth – they came from his blood, from his thoughts. He was on the rack, his blood flowed and nerves trembled. I saw that pale face assume a brighter expression: the divine soul shone from his eyes, and from every feature; he becomes as beauteous as only spirit and enthusiasm can make their worshippers.”

Robert Schumann heard Liszt play in Leipzig, where he reviewed the concert for the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik.

“Liszt played. The demon began to flex his muscles. [Another “demon” reference!] He first played along with the audience, as if to feel them out, and then give them a taste of something more substantial until, with his magic, he had ensnared each and every one and could move them this way or that as he chose. It is unlikely that any other artist has the power to lift, carry, and deposit an audience to such a high degree. In listening to Liszt we are overwhelmed by an onslaught of sounds and sensations; in a matter of seconds we have been exposed to tenderness, daring, fragrance, and madness. The instrument glows and sparkles under the hands of its master. This has all been described a hundred times, but it has to be heard and seen to be believed.”

In Russia, the critics were not disposed to like Liszt at all. The St. Petersburg critic Vladimir Stasov wrote in his memoirs:

“Liszt was wearing a white cravat and various orders [medals] jangled from the lapels of his frock coat. He was very thin and stooped. I did not find his face handsome at all. I at once strongly disliked this mania for decorations and had as little liking for the saccharine, courtly manner Liszt affected with everyone he met.

He played and our misgivings shrank to meaningless insignificance. We had never in our lives heard anything like this; we had never been in the presence of such brilliant, passionate, demonic temperament, at one moment rushing like a whirlwind, at another pouring forth cascades of tender beauty and grace. Liszt’s playing was absolutely overwhelming.”

One more! Henry Reeves, an Englishman who heard Liszt play in Paris, leaves us with a description of the sort of concert-concluding “faint” that Liszt would occasionally stage in order to keep his audiences at the edge of their seats.

“I saw Liszt’s countenance assume that agony of expression, mingled with radiant smiles of joy, which I never saw on any other human face except in the paintings of our saviour. His hands rushed over the keys, the floor on which I sat shook like a wire, and the whole audience were wrapped in sound, when the hand and frame of the artist gave way. He fainted into the arms of the friend who was turning pages for him and was carried out off the stage. The effect of this scene was really dreadful. The whole room sat breathless with fear, till Hiller came forward and announced that Liszt was already restored to consciousness and was comparatively well again. As I handed Madame De Circourt to her carriage, we both trembled like poplar leaves, and I tremble scarcely less as I write this.”

These sorts of onstage shenanigans disgusted Liszt’s professional colleagues. Frederic Chopin, Clara Wieck-Schumann, and Felix Mendelssohn for example were appalled by Liszt’s theatrics and the hysterical hero-worship that surrounded him wherever he went.

Sadly – and unfairly – Liszt’s posthumous reputation continues to suffer from his rock star reputation. In particular and to this day, the vast majority of American academic composers reject Liszt’s music out of hand as being the hackwork of a musical scoundrel. (I know of what I speak. In my four years in the Princeton music department – 1972-1976 – I never heard Liszt’s name mentioned in any tone other than disgust. In my six years as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, I never heard Liszt’s name mentioned by a single composition faculty member, ever. He and his music simply did not exist, and we students knew it was best to never mention his name.)

Why all the hate? Part of it was his on-stage antics. Part of it was the regal persona Liszt cultivated off-stage, an attitude that rubbed a lot of his fellow professionals all wrong. But most of it was politics, pure and simple. Liszt was the self-appointed godfather of the Weimar-based “Music of the Future” (Zukunftsmusik) group, which claimed that the “music of the future” was one that would merge literature, poetry and music in works of instrumental music. Liszt’s sycophantic courtiers, toadies and hangers-on wrote often inflammatory (even libelous) essays and articles and books about those composers and musicians who did not subscribe to their ideals. And while many (if not most) of these articles and books and essays had not been sanctioned by Liszt, neither did he repudiate them, and in the end he received the lion’s share of the blame for all the vitriol.

For many composers, the Weimar group was just a bunch of crackpots; Johannes Brahms, for example, called Liszt and his whole “Music of the Future” trip a “swindle.”

And so sides were taken and the animosity has been handed down like a precious heirloom from generation to generation. As a result, when I was a student, my composition professors – who could trace their lineage back to Brahms, Felix Mendelssohn, and the Leipzig Conservatory – continued to reject Liszt and his music as a “swindle”.

But Liszt’s music is most certainly not a swindle. In fact, he was a great composer, the howls and gnashing of teeth we hear from certain academes notwithstanding.

It speaks volumes that even as academic American composers dismiss Liszt’s music, pianists continue to embrace it and love it and perform it as the foundational bedrock of the repertoire that it is. Liszt’s symphonic poems were highly influential, avant-garde works that paved the way for the orchestral music of Richard Strauss, Edvard Grieg, and Bedrich Smetana, to name just a few. His harmonic language was the most advanced of his time and influenced – profoundly – that of his son-in-law, Richard Wagner.

Happy birthday, Maestro Liszt. Our birthday wish is that your music be treated with the love and respect it so richly deserves!

For more on Franz Liszt, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses biography of Liszt, which is part of my “Great Masters” series. It can be examined and purchased on sale now!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More