On June 25, 1910 – 108 years ago today – Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird received its premiere at the Paris Opera House, in a ballet performance produced by Serge Diaghilev, staged by the Ballets Russes, and conducted by Gabriel Pierné. With choreography by Michel Fokine and the Firebird herself danced by the great Tamara Karsavina, The Firebird was a smash, a sensation, a runaway hit from the first. The not-quite 28-year-old Stravinsky was hailed as the successor to the Moguchaya Kuchka, the Russian Five, the group of nineteenth-century composers who put Russian nationalist music on the international musical map: Mily Balakirev, Cesar Cui, Modest Musorgsky, Alexander Borodin, and Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

Writing in the Nouvelle Revue française, the critic Henri Ghéon called The Firebird:

“the most exquisite marvel of equilibrium that we have ever imagined between sounds, movements, and forms: [a] danced symphony.”

There’s no need to quote additional reviews, because one after the other, they echo the one just quoted.

Thanks to The Firebird’s triumph, the young Stravinsky instantly became the star composer of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, in which capacity he would turn out the magnificent Petrushka in 1911 and the seminal The Rite of Spring in 1913.

The Firebird is indeed a beautifully crafted, gorgeously orchestrated piece. And if in truth much (if not most) of it sounds as if it could have been composed by Alexander Borodin or Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov 40 years earlier, there are still enough moments of genuine modernism in it (for example, “The Infernal Dance” and the asymmetrical phrases of the Finale) that the piece sounds suitably up-to-date.

At that triumphant premiere 108 years ago today, no one in the audience would have guessed that a scant few years before Stravinsky was still but a compositional amateur. We hear and read all the time about musical child prodigies but rarely about adult prodigies. Stravinsky was among the greatest adult musical prodigies of all time, and his story bears telling, if for no other reason to remind us that we can accomplish great things at any point of our lives provided we’re determined and not hard work-averse.

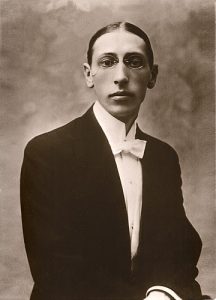

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky was born on June 17 (Gregorian calendar; June 5th according to the Russian, Julian calendar), 1882, in the town of Oranienbaum (today known as Lomonosov), on the Gulf of Finland about 35 miles west of St. Petersburg.

Stravinsky’s family was considered minor nobility: his mother Anna came from the landowning, governing class of 19th century Russia, and his father Fyodor was one of the great operatic bass-baritones of his time, a singer whose career coincided with the golden age of Russian opera.

In 1876, Fyodor became a member of the Imperial Theater in St. Petersburg. It was there that Stravinsky grew up, with his three brothers (two older, one younger), his mother and father, and the servants (as many as five or six), in an eight-room, second-story flat in the center of town.

The St. Petersburg in which Stravinsky grew up was an amazing mix of Western and Eastern Europe, of rich and poor, of city people and country peasantry. The impressions made on the young Stravinsky were indelible; the exotic confrontation and synthesis of East and West that he witnessed on a daily basis cut through to his very soul. It was a confrontation and synthesis that would come to lie at the heart of his music.

Stravinsky’s hated school, made few friends, and was a poor student; in his own words, a student:

“Who studied badly and behaved no better.”

Precisely when Stravinsky began taking piano lessons is still unclear; it was probably around the age of ten. At about the same time he began attending the opera and concerts. As far as his music education went, that was about it: by the age of 17, he was a competent pianist, a hobbyist who announced to his parents his intention of becoming a professional musician. To Fyodor Stravinsky – a professional musician of great renown – Igor’s aspirations were, well, laughable. Accordingly, Stravinsky’s parents insisted that he go to the university to study law, qualify for the civil service, and then get a job.

Precisely when Stravinsky began taking piano lessons is still unclear; it was probably around the age of ten. At about the same time he began attending the opera and concerts. As far as his music education went, that was about it: by the age of 17, he was a competent pianist, a hobbyist who announced to his parents his intention of becoming a professional musician. To Fyodor Stravinsky – a professional musician of great renown – Igor’s aspirations were, well, laughable. Accordingly, Stravinsky’s parents insisted that he go to the university to study law, qualify for the civil service, and then get a job.

In 1901, despite his mediocre academic record, Stravinsky was accepted to the University of St. Petersburg as a law student. Among Stravinsky’s classmates was Vladimir (or Volodya) Rimsky-Korsakov, the youngest son of the composer. At Volodya’s urging, Stravinsky decided to show his early compositions to Rimsky-Korsakov and to seek his advice, a psychologically dangerous step for anyone as sensitive and musically inexperienced as Stravinsky was at the time. Stravinsky picks up the story:

“In 1902 I told him [Rimsky-Korsakov] of my ambition to become a composer and asked his advice. He asked me to play some of my first attempts. Alas! The way he received them was far from what I had hoped. He told me that I must continue my studies in harmony and counterpoint with one or another of his pupils in order to acquire complete mastery of craftsmanship. He finished by adding that I could always go to him for advice, and that he was quite willing to take me in hand when I had acquired the necessary foundation.”

Rimsky-Korsakov was a nice man, and this is about as humane a blow-off as I’ve ever heard. But Stravinsky would not be deterred. He followed Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s advice to that proverbial “T”; and for three years studied music theory and composition with various of Rimsky’s former students. In 1905, having attained a degree of technical competence, Rimsky-Korsakov kept his word and accepted Stravinsky as a private student.

From here things moved quickly. Somehow Stravinsky managed graduate from the university in 1906. As his father had died in 1902, there was no longer any barrier to his musical aspirations. After 1906 he was able to concentrate entirely on his lessons with Rimsky-Korsakov and with them, his extraordinarily rapid development continued. He wrote a series of works – including a symphony – that managed to secure a growing, if local, reputation.

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov died on June 8, 1908. Stravinsky was devastated. But, as with the death of his father six years before, Rimsky’s death had a liberating effect as well. Among the next compositions Stravinsky wrote was a brief orchestral work entitled Scherzo Fantastique, a piece that owes more to the French school – in particular Paul Dukas and Claude Debussy – than to the Russian.

Serge Diaghilev

On the evening of January 24, 1909, Stravinsky’s Scherzo Fantastique was performed in St. Petersburg. Among the audience was the impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was intrigued by what he heard.

On the evening of January 24, 1909, Stravinsky’s Scherzo Fantastique was performed in St. Petersburg. Among the audience was the impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was intrigued by what he heard.

Diaghilev – 10 years older than Stravinsky – was an impresario, whose self-avowed mission was to bring the arts of Russia to the attention of Western Europe in general and Paris in particular. By 1908, Diaghilev had presented in Paris Russian painting, Russian music, Russian opera and, as he put it later, “from opera to ballet was but a step.” In 1908 Diaghilev founded the Ballets Russes – the “Russian Ballet” – as a showcase for Russian dancers and designers.

At Diaghilev’s request, Stravinsky orchestrated a couple of Chopin piano works for the inaugural, 1909 season of the Ballets Russes. But even as the first season approached, Diaghilev and his people were making plans for the second, 1910 season of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev wrote:

“I need a ballet and a Russian one – the first Russian ballet, since there is no such thing – there is Russian opera, Russian symphony, Russian song, Russian dance, Russian rhythm – but no Russian ballet. And that is precisely what I need, to perform in May of the coming year in the Paris Grand Opera.” [For reasons his own, Diaghilev clearly considered Tchaikovsky’s ballets to be naught but chopped cabbage!]

Diaghilev’s new, real Russian ballet was to be based on the Russian folk-tale of the Firebird. Diaghilev first offered the commission to the composer Anatol Liadov, who turned it down. He then considered a composer named Fyodor Akimenko, but then decided Akimenko didn’t have the right stuff. He then approached Nickolay Tcherepnin, but Tcherepnin wasn’t interested. A frustrated Diaghilev fired off a telegram to his Chopin arranger: was Stravinsky willing to take on a major commission?

Hey: did the Tsar poop in the Kremlin?

Stravinsky managed to turn out the 45-minute score in under six months, lightening quick by his meticulous method of working.

Diaghilev told his dancers during the final rehearsal, pointing to Stravinsky:

“Mark him well; he is a man on the eve of celebrity.”

Diaghilev, as usual, was right; The Firebird was a triumph. For the public as well as the press, it was a fully homogenized “Russian ballet product,” just the sort of thing that had been hoped for and expected from a company called the “Ballets Russes.” And for Stravinsky, June 25, 1910 marked – truly – the beginning of a long and magnificent compositional career.

Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More

For lots more information of Stravinsky and The Firebird, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses biography of Stravinsky in the “Great Masters” series, as well as my survey, “The Great Music of the 20th Century”, both of which can be downloaded on sale now.

Thank you.