On October 7, 1968 – 51 years ago today – the Puerto Rican-born singer and songwriter José Feliciano (b. 1945) performed the Star-Spangled Banner in Detroit, before the fifth game of the World Series between the Detroit Tigers and the St. Louis Cardinals. His rendition caused a firestorm of controversy, one that did serious damage to his career.

The Star-Spangled Banner has been back in the news over the last few years, ever since the quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers – Colin Kaepernick – chose not to stand when it was played before an exhibition game against the Green Bay Packers on August 26, 2016. (I don’t know about you, but 2016 feels like a hundred years ago.)

Depending upon where you stand, Kaepernick was either exercising his constitutional right of free speech or grossly insulting everything the national anthem stands for, including the right to free speech. We need not weigh in here on one side or the other, because the point is that the national anthem means many things to many people, and that many people will get very upset when they perceive that someone has messed with the Star-Spangled Banner.

Taking a knee is one thing but performing the anthem in a manner that can be perceived as a desecration is another thing altogether. I’m not referring to the canine ululations of such singers as Mariah Carey and Christina Aguilera, whose melisma-packed (or plagued) performances of the Star-Spangled Banner can run the length of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal. Neither am I referring to those brick-brained performers who, on national television, have managed to disgrace themselves (and their progeny, for generations to come) by forgetting its words: Michael Bolton, Keri Hillson, Sami Hagar, and once again, Christina Aguilera. Rather, I’m referring to performances that in their unique interpretive style have, for whatever reason, caused genuine controversy.

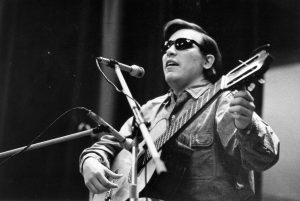

I would ask a rhetorical question: has there ever been a sweeter, gentler, less offensive performer than José Monserrate Feliciano García, best known simply as José Feliciano? Born blind due to congenital glaucoma, he took up the acoustic guitar at the age of nine. Blessed with a clean, flexible, extremely attractive voice, he began performing professionally in 1962, at the age of 17. In 1963 he was “discovered” while performing at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village and was immediately signed by RCA Victor, which released his first single (that is, a 45-rpm record) in 1964. He had his first million seller in 1968, when RCA released a 45-rpm of Feliciano singing Michelle and John Phillips’ California Dreamin’ on side “A” and the Doors’ Light My Fire on side “B”. 1968 was indeed a career year for Feliciano; he took home two Grammy Awards that year, one for Best New Artist and one for Best Pop Male Performance. He had, at the age of 23, achieved international stardom as “an innovative crossover artist with soul, folk and rock influences, infused with a substantial Latin flair.”

His fame peaking, Feliciano was invited to sing the national anthem by the Detroit Tigers’ broadcast announcer Ernie Harwell. Feliciano ventured out onto the field with his guide dog and an acoustic guitar. A video of his rendition that day – soulful, deeply expressive and to my ears very beautiful – can be found at the top of this post. No doubt: Feliciano took liberties with the Star-Spangled Banner, although compared to the screeching, cats-copulating-on-corrugated-metal-styled renditions we are accustomed to hearing today, Feliciano’s version is downright noble. But that’s not what many in the crowd and watching on TV across America thought that day 51 years ago, and the booing started before he was even finished.

In fact, the real problem wasn’t Feliciano’s interpretation of the national anthem; no, the real problem was that it was October of 1968, when, very much like today, the United States was at war with itself.

Two weeks ago, in my Music History Monday post for September 23 entitled “Paul is Dead”, we observed just a few of the events that were tearing America apart at exactly that time: the disastrous progress of the war in Vietnam and the realization that President Lyndon Johnson had been lying to the American people about the war all along; the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy; an intensification of the shattering race riots that had started in 1963 in response to the Civil Rights Movement and now in response to King’s assassination; and the rise of the radical left culminating in the riots around the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Never was the generational divide more keenly felt; never before had so many people come to distrust the national government; perhaps not since the American Civil War had so many people come to distrust their fellow Americans.

What it all meant is that the more conservative elements in the crowd there in Detroit and watching on TV were not likely to appreciate José Feliciano’s presumably “unpatriotic” version of the national anthem. Add to it all Feliciano’s Latino heritage and, well, the merde hit the fan.

Within minutes the telephone switchboard at Tiger Stadium was jammed with hundreds of angry calls. The New York switchboard of NBC – which broadcast the game – likewise lit up like that proverbial Christmas tree with furious callers. The American Legion censured the Detroit Tigers, and the announcer who had hired Feliciano – Ernie Harwell – was, in the end, he lucky to keep his job.

A Detroit Tigers fan named Arlene Raicevich told the Associated Press that Feliciano’s performance “was a disgrace, an insult. I’m going to write my senator about it.”

Another Detroit fan – dude named Bernie Gray – intelligently observed that: “It sounded like a hippie was singing it.”

The slugger Roger Maris – who was in the process of finishing his major league career with the St. Louis Cardinals – told the Boston Globe that: “I don’t think it was the proper place for that kind of treatment. Maybe I’m a conservative.”

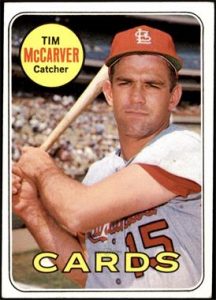

However, Maris’ teammate Tim McCarver had a different view: “Why not that way? People go through a routine when they play the anthem. They stand up and yawn and almost fall asleep. This way, at least they listened.”

Listen they did. And while Feliciano’s rendition did, for a number of years, damage his career, it is most satisfying to know that today, his recording of the Star-Spangled Banner is on permanent display at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Postscript

Two other controversial “interpretations” of the Star-Spangled Banner must be mentioned here, both of which make José Feliciano’s version sound like Mr. Rogers singing Good Morning to You.

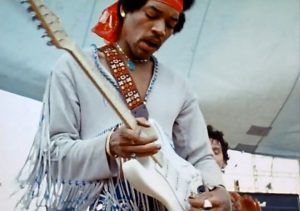

On August 18, 1969 – some 10½ months after game five of the 1968 World Series – Jimi Hendricks closed out the Woodstock Festival with his new band, “Gypsy Sun and Rainbows.” About three-quarters of the way through that final set, Hendrix played a four-minute solo rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner on his Fender Stratocaster. It was – and remains – a stunning, wailing, distortion-filled improvisational performance, in which (it was said) that the feedback he generated was meant to depict bombs falling and exploding in Vietnam. Hendrix, who himself had served in the Army’s 101st Airborne Division, made his feelings clear: he was not anti-American; rather, he was anti-war.

We’ve saved the best for last. It was on July 25, 1990 that Roseanne Barr attempted to sing the national anthem at San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium before a game between the San Diego Padres and the Cincinnati Reds.

Ms. Barr fondly recalled:

“I started too high. I knew about six notes in that I couldn’t hit the big note. So I just tried to get through it, but I couldn’t hear anything with 50,000 drunk a—holes booing, screaming ‘you fat [expletive],’ giving me the finger and throwing bottles at me during the song they ‘respect’ so much.”

Roseanne concluded her performance by grabbing her crotch, spitting on the field (to her right), and then marching off with her arms raised as if to further taunt the booing fans.

(A parenthetical observation. The long departed but still greatly missed San Francisco-based entertainment critic John Wasserman once referred to John Belushi – unkindly but not inaccurately – as “a pig in a man’s body.” Might Roseanne Barr be Belushi’s natural female counterpart? Just askin’.)

Madame Barr’s performance was not well received by anyone. No one in the Padres front office was willing to own up to having invited Barr to sing. President George H. W. Bush condemned her performance as “disgraceful.” The conservative columnist George Will called her a “slob” and compared her performance to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

When she was later asked if she regretted showing up to the stadium that day, Roseanne replied:

“Do I regret that the next day all of my projects were cancelled, and [that] I had to have LAPD stand on my roof and protect my life and my kids for two years? Do I regret not being able to go out in public for about one full year without being spit on in restaurants, [and at] 7-Eleven? Do I regret Rolling Stone selling t-shirts with my picture in the middle of a gun target? Do I regret that every ‘feminist’ in Hollywood ran the other way when they saw me at Hollywood functions, to avoid taking a picture with me? Do I regret President George Bush 1 calling me disgraceful on television as he unleashed Desert Storm? Do I regret not one person in Hollywood defending me? Do I regret the dozens of death threats I received?

“Actually, no, I don’t regret any of it.”

On this, we’ll just have to take Roseanne Barr at her word.

If you haven’t already, please join me on Patreon.

Listen to the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More