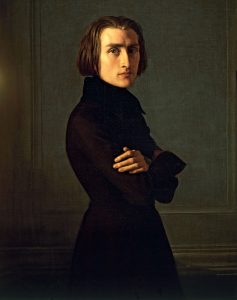

We mark the birth on December 24, 1837 – 181 years ago today – of Cosima Liszt von Bülow Wagner: the illegitimate daughter of Franz Liszt; the wife of the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow; and then the mistress and wife of Richard Wagner. As Wagner’s wife, she became his protector and his muse. According to Ernest Newman, whose four-volume, 2429 page biography of Wagner remains an essential reference, Cosima was “the greatest figure that ever came within Wagner’s circle”.

As Wagner’s widow, she became the “keeper of the Wagnerian flame”; she rescued and made profitable Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival and protected Wagner’s artistic legacy with a ferocity ordinarily associated with wolverines and spotted hyenas.

Cosima Liszt von Bülow Wagner remains a controversial figure. Her racism and anti-Semitism were even more virulent than Wagner’s, and by the time she died – in 1930 – the close association of Wagner, Hitler and the Nazis was becoming institutionalized. Writing in 1930, Cosima’s first biographer – Richard du Moulin Eckart – asserts that she was “the greatest woman of the century”. According to the critic and librettist Philip Hensher, writing in 2010: “Wagner was a genius, but also a fairly appalling human being. Cosima was just an appalling human being.”

More than anything else, though, she was a survivor: a powerfully ambitious person who understood that given the time and place of her birth, her ambitions could only be realized through the men in her life.

Cosima was born in the northern Italian town of Bellagio, on Lake Como, the second child of the pianist and composer Franz Liszt and his Paris-socialite mistress, the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult. Cosima was baptized as Francesca Gaetana Cosima, with an annotation on her baptismal certificate reading: “illegitimate”.

By 1839, Liszt and his mistress Marie d’Agoult were on the outs. The two year-old Cosima and her elder sister moved in with Liszt’s mother in Paris. By 1845, Liszt and Marie d’Agoult were no longer on speaking terms, and he forbade her from having any contact with her children. And while the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult accused Liszt of trying to steal her children, she gave up fighting for them soon enough, as her social status in Paris was clearly more important to her than her illegitimate children

Cosima did not see her mother for five years – until 1850 – despite the fact that they lived in the same city and that Marie had full visiting rights. As for Liszt: although he never denied his paternity and he paid for all his kids’ expenses, he saw them not once in the nine years from 1844 to 1853. Cosima grew up yearning for her parents in a house full of women without any paternal presence. It goes without saying that she nursed a profound sense of rejection and abandonment.

And then things got much worse.

In 1850 Liszt’s next lady friend – the Princess Carolyne Wittgenstein – convinced him to turn the children over to her own governess: a tyrannical septuagenarian named Madame Patersi de Fossombroni whose “teaching regimen” has been likened to that used for breaking in horses. Cosima, not quite thirteen when Madame Patersi came into her life, spent the remainder of her adolescence in what has been described as “a living hell”: a loveless, joyless, often sadistic atmosphere. She survived by creating a mask of icy respectability and by nurturing hatreds so vehement that she would, in time, make Wagner look Mr. Rogers by comparison. In particular she hated Jews, despite the fact that one of her great-grandfathers had been Jewish.

In October of 1853, Liszt and his “entourage” (including Princess Carolyne, Carolyne’s daughter Maria, and Richard Wagner) swept into Paris to finally visit the children. Cosima, not quite 16 years old at the time, was as awkward as they come: tall, gangly, gawky, razor thin, with a huge beaked nose. (Her siblings called her the “stork” and “the ugly duckling”. Nice.)

Wagner took no notice of Cosima, although Cosima noticed him. He read from his recently completed poem, The Ring of the Nibelungen. Princess Carolyne’s daughter Maria recalled:

“I can still see Cosima’s rapturous expression with tears running down her sharp nose.”

At the age of seventeen, Cosima – together with her brother and sister – was unceremoniously shipped off from Paris to Berlin, where they were placed in the care of Franziska Elisabeth von Bülow. Madame von Bülow was an old friend of Liszt’s, and it’s generally believed that the move was engineered – again! – by Liszt’s mistress Princess Carolyne Wittgenstein, this time to deny them contact with their mother, Marie D’Agoult. (Nice!) After living in Paris for most of her life, Cosima was truly miserable: she hated Berlin. But it was there that she met her governess’ son, a 25 year-old pianist and conductor named Hans Guido von Bülow.

On August 18, 1857, the nineteen year-old Cosima Liszt left her miserable adolescence behind and began her miserable young adulthood by marrying the now 27 year-old Hans von Bülow.

Hans von Bülow (1830-1894)

Von Bülow was born in Dresden in 1830. Growing up in Dresden, he had the opportunity to hear Wagner’s music and to watch Wagner conduct, and von Bülow fell in love. In 1846 – by which time the 16 year-old von Bülow had developed into a formidable piano virtuoso – he and Wagner began corresponding. Wagner thought highly of his young acolyte, and encouraged his musical ambition despite the fact that von Bülow’s parents insisted that he study the law. Well, when the 20 year-old Hans von Bülow heard Franz Liszt conduct the premiere of Wagner’s Lohengrin in Weimar in 1850, that was that: he left law school, went to Zurich (where Wagner was living) and with Wagner’s help secured a position conducting at the Zurich opera.

In 1851, he became a student and protégé of Franz Liszt, and in 1857 he married the stork: Liszt’s daughter Cosima. They had two daughters – Daniela and Blandine – born respectively in 1860 and 1863.

In 1864 Hans von Bülow was appointed to the position that made him famous: Hofkapellmeister – court conductor – in Munich. It was in this capacity that von Bülow conducted the premieres of Tristan and Isolde in 1865 and The Mastersingers of Nuremburg in 1868.

Back to Cosima Liszt von Bülow

Wagner renewed his acquaintance with the now 19 year-old Cosima in late August of 1857. Cosima and Hans von Bülow had just been married – on August 18th, 1857 – and a proud Hans von Bülow came to visit “the master” in Zurich in order to show off his new wife.

Wagner was 24 years Cosima’s senior, and at the time of the visit she thought him to be self-centered and vulgar.

Of course, this was before Cosima had become disenchanted with her marriage to Hans. Though he was an outstanding pianist and conductor, von Bülow was no Richard Wagner or Franz Liszt, and Cosima desperately needed to play the role of an indispensible muse to a great man. On January 8, 1869, after nearly 12 years of marriage, Cosima confessed to her diary:

“It was a great misunderstanding that united us in matrimony. I still feel the same for him as I did twelve years ago: great sympathy for his destiny, delight in his gifts both of mind and heart, a real esteem for his character, together with complete incompatibility of disposition. In the very first year of my marriage I was in such despair that I wanted to die.”

By the time Cosima wrote this – in 1869 – she’d been sleeping with Wagner for six years (since 1863), and openly living with him for three years (since 1866).

The “Affair”

In late November of 1863, Wagner decided to visit the von Bülows, who were at the time living in Berlin. While Hans was at work one day, Wagner and Cosima went out for a drive. Years later, in his autobiography, Wagner described the moment that changed their lives:

“Our jesting died away in silence. We gazed speechless into each other’s eyes; an intense longing to speak the truth overpowered us and led to a confession, of the boundless unhappiness that weighed upon us. With tears and sobs we sealed our confession to belong to each other alone.”

A typical Wagnerian “dramatization”? No doubt. But there is also no doubt that Richard Wagner and Cosima Liszt von Bülow did indeed fall in love with each other in November of 1863.

Wagner and Cosima – both illegitimate children themselves – wasted little in conceiving their own. On April 12, 1865, Cosima gave birth to a third daughter, who was named Isolde. Hans von Bülow spent the rest of his life pretending that the child was his, but he knew that the child was Wagner’s. But – amazingly – he continued to champion Wagner’s music.

Franz Liszt, for one, was horrified by his daughter’s behavior, which he considered “an abomination”. He correctly foresaw the scandal it would create and the damage to von Bülow’s career and psyche it was cause.

On February 17, 1867, Cosima gave birth to another daughter, who was named Eva, and on June 6, 1869, she gave birth to yet another child, this one a boy named Siegfried.

It was with Siegfried’s birth that Cosima finally came clean and asked von Bülow for a divorce. Von Bülow – who had to quit his conducting job in Munich because of the scandal – behaved with a degree of dignity and good will that neither Cosima nor Wagner deserved. The divorce was granted on July 18, 1870. Wagner and Cosima were married a month later on August 25, 1870. Wagner was 57 years old and Cosima was 32.

Cosima had her man and had found her calling: a muse to greatness. For the next 60 years, she protected and inspired her husband and secured his legacy after his death in 1883. Like her or hate her, she was one tough lady.

For lots more on Cosima, Wagner, and Franz Liszt, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses surveys The Music of Richard Wagner and Great Masters: Franz Liszt.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More