A few, necessary words before moving on to today’s post.

Our hearts bleed for the events currently playing out in Israel and Gaza.

Frankly, there are no words.

Today is also the 14th anniversary of my wife Diane’s death; she died at the age of 35 on October 16, 2009.

Again, there are no words.

Our grief notwithstanding, we soldier on – as we must – doing what we can to make our individual “worlds” a better place. For me, here on Patreon, that means publishing my blogs and podcasts, and thus – hopefully – allowing us to observe the best of the human spirit through our music.

That’s my gig, inadequate though it feels on days like today.

We mark the premiere on Wednesday, October 16, 1912 – 111 years ago today – of Arnold Schoenberg’s dazzling, controversial, and in all ways extraordinary work Pierrot Lunaire, at Berlin’s Choralion–saal. The premiere was preceded by a mind-blowing forty rehearsals!

(For our information: chamber music premieres typically receive 3 to 5 rehearsals, max. It’s never enough, but that’s just how it is. Forty rehearsals for Pierrot Lunaire? Unheard of!)

Happy Coincidences!

As those of you who follow me on Patreon are aware, I’ve been serializing my book, The Composer is Always Right (CIAR), on Sundays, for over two years now. Yesterday’s installment was number 114; we have 27 more to go. For the first and what will be the only time, the topics of this week’s Music History Monday and Dr. Bob Prescribes posts and CIAR installment all deal with Arnold Schoenberg, the premiere of Pierrot Lunaire, and what, specifically, Schoenberg’s wife Mathilde made him “do.” As such, there will be some overlap between Music History Monday, Dr. Bob Prescribes, and The Composer is Always Right this week, for which I know will be forgiven.

The Schoenberg Dilemma (The Schoenberg Dichotomy)

The music of Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) continues to present a unique dilemma, a unique dichotomy. On one hand, no major twentieth-century composer’s music has been – and continues to be – more misunderstood and disparaged by the general listening public than Schoenberg’s. On the other hand, along with Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky, no twentieth-century composer has exerted a greater influence on the compositional community than has Arnold Schoenberg.

On the first page of his wonderful little book, entitled Arnold Schoenberg (Princeton University Press, 1975), the American pianist and musicologist Charles Rosen speaks to this “Schoenberg dilemma”:

“In 1945, Arnold Schoenberg’s application for a grant was turned down by the Guggenheim Foundation. The hostility of the music committee to Schoenberg and his work was undisguised. The seventy-year-old composer had hoped for support in order to finish two of his largest musical compositions, the opera Moses und Aaron and the oratorio Jacob’s Ladder, as well as several theoretical works. Schoenberg had just retired from the [faculty of the] University of California at Los Angeles; since he had been there only eight years, he had a pension of $38.00 a month with which to support a wife and three children aged thirteen, eight, and four. He was obliged, therefore, to spend much of his time taking private pupils in composition. This ‘enforced’ teaching enabled him to complete only one of his theoretical works, the Structural Functions of Harmony. The opera and oratorio were still unfinished at the composer’s death six years later.

Recognized internationally as one of the greatest living composers, considered the finest of all by many, acknowledged, with Igor Stravinsky, as one of the two most influential figures in contemporary music since Debussy, Arnold Schoenberg at the end of his life continued to provoke an enmity, even a hatred, almost unparalleled in the history of music. The elderly artist whose revolutionary works had raised a storm of protest in his youth is a traditional figure, but in old age his fame is unquestioned and dissenting voices have been stilled. In Schoenberg’s case, the dissent may be said to have grown with the fame.”

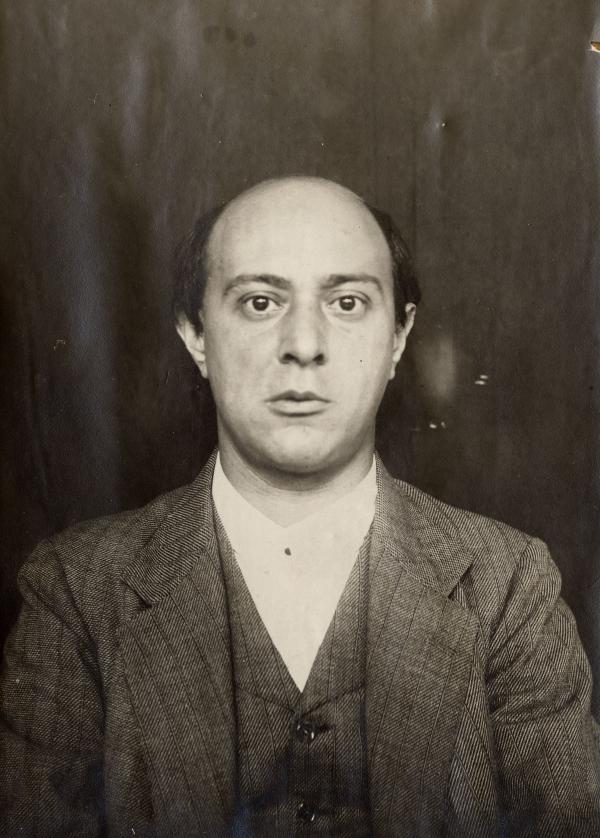

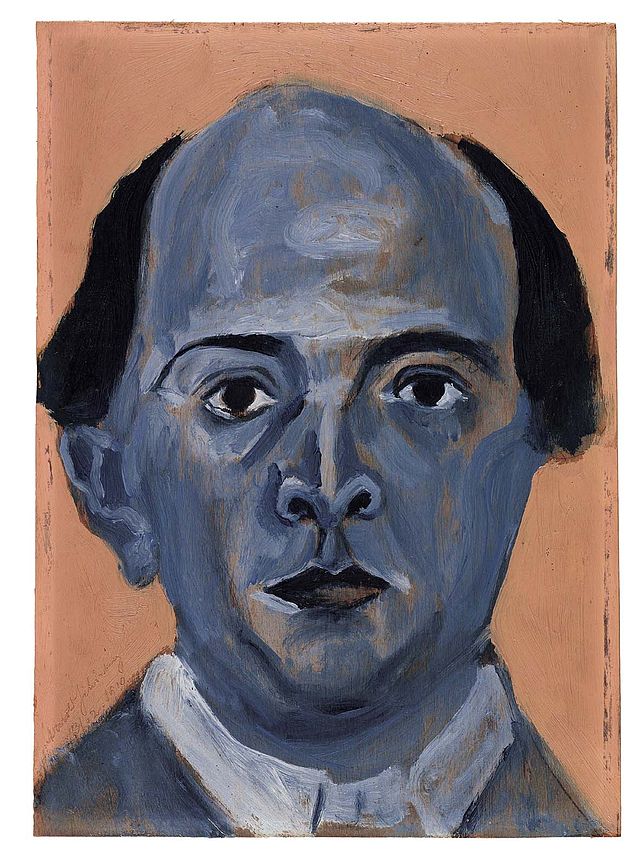

Given the fear and loathing the name “Arnold Schoenberg” continues to inspire 72 years after his death you’d think he was some sort of Nosferatu-like monster who shot puppies for sport and refused to recycle. Rather, he was a short (around 5’2”), prematurely bald dude with a baritone voice couched in a soft Viennese accent, someone who loved kids (he was still fathering them into his mid-60’s), ping-pong, and tennis (he was, for a period during the late 1930s, George Gershwin’s regular tennis partner). He was, for our information, terrified (not too strong a word) of the number 13 (a fear known as “Triskaidekaphobia”).…

Continue reading, and listen without interruption, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!Listen and Subscribe to the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More

The Robert Greenberg Best Sellers

Best selling products

-

Mozart In Vienna

-

Great Music of the 20th Century

-

Understanding the Fundamentals of Music

-

Music as a Mirror of History

-

How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, 3rd Edition

-

Great Masters: Mahler — His Life and Music

-

The Chamber Music of Mozart

-

The Concerto

-

The 30 Greatest Orchestral Works

-

Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas