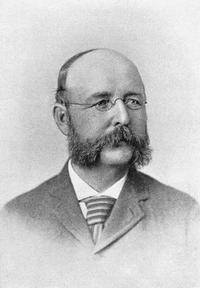

In the world of concert music, January 9th was a quiet day. The most noteworthy event to fall on this date was the birth – in 1839 and in Portland, Maine – of the American composer and pedant John Knowles Paine. In 1874, at the age of 35, Paine became not just the first Professor of Music at Harvard University, but the first academic professor of music at any American university. It was a position he held until 1905; he died in 1906 at the age of 67.

In the world of concert music, January 9th was a quiet day. The most noteworthy event to fall on this date was the birth – in 1839 and in Portland, Maine – of the American composer and pedant John Knowles Paine. In 1874, at the age of 35, Paine became not just the first Professor of Music at Harvard University, but the first academic professor of music at any American university. It was a position he held until 1905; he died in 1906 at the age of 67.

Let us give Professor Paine his due up front: he was, in his maturity, an extremely skilled compositional craftsperson. Having trained in Berlin, he came home to the United States and spent his career composing concert works that are stylistically indistinguishable from his German models (except for the fact that they are not – artistically – as good as his German models; too bad). In this imitation-of-musical-things-German Paine was the poster-child for pretty much every mid-to-late nineteenth century American composer (excepting the young Charles Ives), all of who spent their compositional careers trying (unsuccessfully) to “be like Brahms”.

(In reference to Paine’s music, this “be-like-Brahms” thing is ironic, because despite the fact that the local Boston critics and audiences adored Paine’s work, they were unsparing disdainful of Brahms’ own music. It was the well-known Boston music critic Philip Hale who proposed that the space above the doors of Boston’s brand-new Symphony Hall all bear the inscription: “Exit – In Case of Brahms”.)

Paine was the prototypical late-nineteenth/early twentieth century American music pedagogue: a German in everything but birth; fanatically reverent of the “Euro-classics” and equally contemptuous towards anything that smacked of being “American”; a snob with a built-in abhorrence towards any music he perceived as being “popular”, from ragtime to early jazz, American musical theater and even the marches of John Philip Sousa.

Sadly, Paine’s prejudice against the cultural products of his native U.S. of A. (excepting barbershop quartet music, which he composed in conspicuous quantity as a young man) was to have a lasting and pernicious effect on American musical culture. You see, Paine churned out scads of likewise prejudiced Harvard students – both music majors and non-majors – who as musicians, politicians, leaders of business, heads of foundations, and orchestra and opera board members continued to endorse and apply those prejudices against American music well into the twentieth century.

So even as we must admire Paine for his revolutionary (at its time) insistence that music had a place among the liberal arts in the American academy and that, according to Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians, “he awakened a regard for music among generations of Harvard men”, we must also recognize that Paine and those who followed him (like Horatio Parker at Yale University and George Chadwick at the New England Conservatory) helped reinforce a bias against American music that lasted well into the twentieth century.

It is with mixed feelings, then, that we bid you, Herr Professor Paine, a … a somewhat happy birthday. May you spend it listening to the music of Scott Joplin, Charlie Parker, and Cannibal Corpse.