Some birthday greetings to four wonderful musicians before diving into the rather

Four Birthdays

A buon compleanno (“happy birthday” in Italian) to the legendary Italian conductor (and cellist) Arturo Toscanini, who was born on March 25, 1867 – 152 years ago today – in the north-central Italian city of Parma (the home of Parmigiano-Reggiano, or “parmesan” cheese and the simply exquisite cured ham known as Prosciutto di Parma). Toscanini was as famous for his incendiary temper as he was for his streamlined, rhythmically propulsive, honor-the-composer’s-score-at-all-costs performances. Decorum and good taste

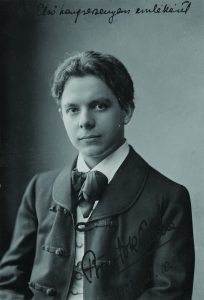

A boldog születésnapot (“happy birthday” in Hungarian) to the killer-great Hungarian composer and pianist Béla Bartók, who was born on March 25, 1881 – 138 years ago today – in what was then the town of Nagyszentmiklós, in the Kingdom of Hungary in Austria-Hungary. (It was a source of ever-lasting pain for the adult Bartók that the town and district in which he grew up was ceded to Romania in 1920 when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up by the post-World War One Treaty of Trianon. Today Bartók’s home town is known as Sânnicolau Mare, which can be found on the westernmost edge of Romania.)

(Under the heading of way too much information, in the Banat Bulgarian dialect the town is known as Smikluš; in Serbian as Сент Николаш /Sent Nikolaš, in German as Groß Sankt Nikolaus, and in English as “Great St. Nicholas”. Yup: Old St. Nick!)

A rather melancholy happy birthday to the recently, dearly departed singer, songwriter, pianist and activist Aretha Louise Franklin, who was born in Memphis, Tennessee on March 25, 1942: 77 years ago today. She passed away just seven months ago, in Detroit, on August 16, 2018.

Respect.

Finally, a rousing happy birthday to the singer, songwriter, pianist, and philanthropist Reginald Kenneth Dwight, who was born on March 25, 1947, 72 years ago today. For our information, on January 7, 1972, Dwight legally changed his name to Elton Hercules John.

In 1987, John was granted the honor of a formal coat-of-arms. Though I’m certainly not an expert on these things, I would nevertheless suggest the Sir Elton’s coat-of-arms has got to be among the coolest ever. Set in black, white, red and gold, the crest features a piano keyboard and four records. The Spanish motto reads “el

A Painful Death

On an entirely different note, this day also marks the death of the superlative French composer and musical revolutionary extraordinaire, Achille-Claude Debussy, who died in Paris on March 25, 1918 – 101 years ago today – at the all-too-young age of 55.

For myself, I will confess to having a grim interest in how composers died. (I’m not talking about anything as perverse as the Austrian composer Anton Bruckner’s fascination with corpses; Bruckner’s idea of a hot date was a trip to the Vienna morgue to see the bodies. The more violent the death suffered, the more fascinated – and presumably happier – Bruckner was. Most definitely a bit twisted, Bruckner was what today would be called a “Death Hag.”)

But back to my interest in knowing how composers died. It is, for me, just another way to humanize them; to feel closer to them and identify with them as real people; and having done so, to feel viscerally closer to their music.

In life, Claude Debussy was something of a pill. A borderline narcissist, Debussy had the

There are good deaths and there are bad deaths; Debussy’s was a very bad death.

The illness that would kill him on March 25, 1918 first became noticeable – painfully noticeable – at the end of 1908: severe rectal pain and, by early 1909, almost daily bleeding. Debussy saw a doctor, who prescribed a change of diet and lots of exercise (perhaps “drink plenty of fluids” as well?). In a letter to his publisher Jacques Durand written in early 1909, Debussy described his condition:

“For two days I never stopped suffering miserably. Only with the help of a variety of tranquilizers – morphine, cocaine, and other such lovely drugs – was I able to cope, but at the price of total stupor.”

This is how Debussy lived his life for the next six years. And while the summer of 1915 saw the 53-year-old Debussy at the height of his creative powers, it also saw the fateful diagnosis of rectal cancer.

Debussy’s health cratered in the fall of 1915; he wrote the violinist Arthur Hartmann:

“Of course this illness had to come at the end of a spell of good work. I tell you, old man, it makes me weep. And in addition to all this misery, these morphine injections turn you into a walking corpse and completely annihilate your will. When you want to go to the right, you go to the left, and do all sorts of stupid things of that kind. If I were to give a detailed account of my misfortunes, you would be reduced to tears, and [your wife] would think you had lost your wits!”

Things came to a head on December 7, 1915, when Debussy underwent colostomy surgery. The day before, on December 6, he had written Jacques Durand:

“My dear Jacques, tomorrow is definitely the day I’m being operated on. I didn’t have time to send out invitations; next time I’ll make an effort to plan ahead.”

The surgery – frighteningly crude by today’s standards – was followed by a radiation treatment almost too terrifying to contemplate. Over a period of days and even weeks, Debussy’s doctors inserted pellets or tubes filled with radium into his rectum in an attempt to destroy the remnants of his tumor. The treatments were agonizingly painful, “and highly problematic because the optimal duration of exposure to radiation was not known.” On February 6, 1916 Debussy wrote to a friend:

“The doctors give me hope of some improvement in a couple of weeks. But I haven’t much confidence, and radium rather abuses its right to be mysterious.”

Debussy composed almost no music in 1916. Distraught, depressed, and on de ropes, Debussy wrote this on June 8, 1916:

“Since Claude Debussy is no longer writing music, he has no excuse for being alive. I have no hobbies; I was never taught anything but music. Things are endurable only on condition that I can compose; but to keep tapping a brain that sounds hollow is an unpleasant business.”

But a month later, on July 3, 1916, Debussy rallied, and informed his publisher that – damn it all – he was going back to work:

“I cannot say that I feel any better, but I have made up my mind to ignore my health, to get back to work, and to be no longer the slave of this over-tyrannical disease. We shall soon see. If I am doomed to disappear soon, I wish to have at least tried to do my duty.”

The product of this dogged compositional determination was Debussy’s Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano, which turned out to be his last major work. Somehow, Debussy found the strength to perform the piano part himself when the piece received its premiere on May 5, 1917.

Reading Debussy’s letters from these years, all the while contemplating the degree of his almost endless suffering and ongoing physical deterioration is itself a painful experience. And yet he soldiered on, displaying precisely the sort of spirit and courage often (but not always) attributed to those fighting a terminal disease.

The end finally came on the evening of March 25, 1918. World War One was in its final year; the Germans were bombarding Paris with a huge, 256-ton long-range gun (called the “Paris Gun” or “William’s Gun”, it was capable of shelling Paris from as far away as 81 miles). It was ironic: that a composer who had dedicated his life to creating a French musical language free of German influence died while hearing German shells explode in his beloved Paris.

Rest in peace, Monsieur Debussy.

For lots more on the music of Claude Debussy, I would direct your attention to four of my Great Courses surveys: How to Listen to and Understand Great Music; The 30 Greatest Orchestral Works; The 23 Greatest Piano Works; and The Great Music of the 20th Century.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More