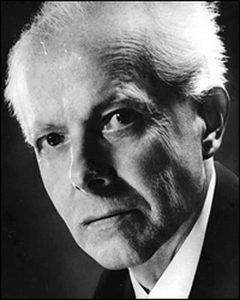

Seventy-one years ago today – on September 26, 1945 – the composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist and Hungarian patriot Béla Viktor Janos Bartók died at the age of 64 in self-imposed exile in New York City. Sixteen years later, in 1961, the composer and conductor Pierre Boulez, the enfant terrible of post-World War Two musical modernism, wrote this about Bartók’s music:

Seventy-one years ago today – on September 26, 1945 – the composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist and Hungarian patriot Béla Viktor Janos Bartók died at the age of 64 in self-imposed exile in New York City. Sixteen years later, in 1961, the composer and conductor Pierre Boulez, the enfant terrible of post-World War Two musical modernism, wrote this about Bartók’s music:

“The pieces most applauded are the least good; his best products are loved in their weaker aspects. His work triumphs now through its ambiguity. Ambiguity that will surely bring him insults during future evaluation. His language lacks interior coherence. His name will live on in the limited ensemble of his chamber music.”

Boulez was not just wrong: he was snotty wrong. And in this he was not alone.

Most of the post-War compositional modernists – which includes most of my own teachers – rejected Bartók because they believed he had squandered his potential as a compositional radical by employing elements of folk-music, neo-tonality, dance rhythms, and Classical era forms to create a body of music that was on occasion – God forbid – viscerally exciting and, even worse, accessible; music that employed such antediluvian elements as tunes and melodic sequences and was “expressive” in an unabashedly Romantic sense.

These post-War modernists considered Bartók to be an evolutionary dead end who composed music during the first half of the twentieth century that was irredeemably irrelevant to the second half of the twentieth century.

Here in the twenty-first century we know better. And it’s not just the fact that it is once again okay for “concert” music to be viscerally exciting. No, what makes Bartók a composer for the twenty-first century is the degree to which his music represents a synthesis of nearly global scope. His compositional language is one of purposeful diversity integrated into a singularly personal musical voice. Bartok’s music offers a model for one of the most important questions facing composers today: in an increasingly global culture, in which “diversity” and “variety” are not just buzzwords but real cultural descriptors, how might a composer go about incorporating and reconciling some aspects of that diversity into an integrated and personalized musical language?

Here’s what Bartók did.

He started with impeccable technical credentials, having finished his training as a pianist and composer at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest (where he went on to teach as a professor of piano from 1907-1934). Youthful infatuations with the music of Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy strengthened his ear for late Romantic German compositional practice and French timbral nuance. His embrace of Hungarian nationalism in his early twenties led to a lifelong fascination with the indigenous music of not just his native Hungary, but of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, Turkey, and North Africa as well. His immersion in these rich, non-Western musical environments changed forever the way he perceived melody, harmony, and rhythm. Bartók’s enduring affection for Classical era discipline manifested itself in music of great clarity and precision. Add to this his rock ‘n’ roll soul and his deep and moral humanity and you’ve got the recipe for a personal musical language of extraordinary breadth, power, and relevance.

In a twenty-first century musical environment in which so many composers are attempting to reconcile and synthesize something of the diversity around us, Bartók’s music has become the ideal role model!

Touché, Monsieur Boulez! How do you like them apples?