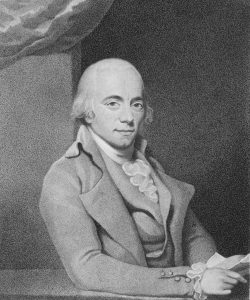

On January 23, 1752 – 265 years ago today – the composer, harpsichordist, pianist, organist, conductor, teacher, music publisher and editor, and piano manufacturer Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Clementi was born in Rome. Remembered best today for his six delightful Sonatinas for Piano published as Op. 36, he was, in fact a prodigious composer; his collected works (published in Bologna by Ut Orpheus) fills 60 volumes!

On January 23, 1752 – 265 years ago today – the composer, harpsichordist, pianist, organist, conductor, teacher, music publisher and editor, and piano manufacturer Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Clementi was born in Rome. Remembered best today for his six delightful Sonatinas for Piano published as Op. 36, he was, in fact a prodigious composer; his collected works (published in Bologna by Ut Orpheus) fills 60 volumes!

In his own lifetime, Clementi was considered by his contemporaries to be one of the handful of greatest living pianists.

Wolfgang Mozart – almost exactly four years younger than Clementi – quit his day job in Salzburg and settled in Vienna in May, 1781. He was 25 years old. Mozart knew his worth, and he knew – as well as we do, today – that in 1781 he was the greatest pianist and composer in the world. To his mind, among his first tasks in Vienna was to make sure that everyone in that fine city understood his greatness as well. By December 1781, Mozart had gone a long way towards accomplishing that task.

By December of 1781, Mozart considered Vienna to be his turf, and he was not kindly disposed towards anyone busting in on his turf. That’s precisely what happened on December 24, 1781, when Mozart was invited by Emperor Joseph II himself to come to court and compete with an Italian pianist who had just arrived in Vienna. That Italian pianist’s name was Muzio Clementi.

Clementi was in the midst of a three-year musical tour of Europe. Having arrived in Vienna in December of 1781, he agreed to participate in a musical contest with the local light, a dude named Mozart, for the entertainment the Emperor and his be-wigged guests on Christmas Eve.

Clementi described his first impression of Mozart this way:

“On entering the Emperor’s music room I found there someone whom, because of his elegant appearance, I took for one of the Emperor’s chamberlains; but scarcely had we begun a conversation when we soon recognized each other as Mozart and Clementi.”

Mozart picks up the story from there.

“The Emperor (after Clementi and I had paid each other enough compliments) declared that Clementi should play first. ‘La senta chiesa cattolica!’ – [‘Let us hear from the Catholic Church’] He said, as Clementi is from Rome. He improvised and played a sonata.”

Clementi played his Sonata in B-flat Major, Op. 24 No. 2. It is a fluent, glittering, virtuosic piece. It lacks Mozart’s trademark melodic grace and harmonic imagination, but then again, so does everyone else’s music.

Following Clementi’s performance, it was Mozart’s turn. Writes Mozart:

“The Emperor said to me: ‘Allons, off you go.’ I improvised in turn and played some variations.”

The variations Mozart refers to were improvised on a theme provided him by the Emperor or one of his guests. It was a march from the opera The Samnite Marriage, composed in 1776 by the French composer André Grétry. We know this because sometime during the next couple of days Mozart sat down and wrote out a theme and variations form piano piece based on a march from Grétry The Samnite Marriage. Mozart’s notated variations are a very close if not an exact replica of what he improvised; jotting down a previous evening’s improvisation was something he did all the time.

Yes, I hate him for that, too.

Among the audience that Christmas Eve was Emperor Joseph II’s younger brother Leopold and his wife, the Grand Duchess Maria Luisa. Like Emperor Joseph II, the Grand Duchess was a big music fan. However, unlike Joseph II, her tastes ran decidedly towards Italian music and musicians. (Ten years later, Grand Duchess Maria Luisa went down in music history when she dismissed Mozart’s Italian-language opera “The Mercy of Titus” as being “porcheria tedesca”: “German swinishness”.) The Grand Duchess made a private wager with Emperor Joseph II: she bet that Clementi would “win” the duel, whereas the Emperor put his money on Mozart. We’ll discuss the outcome of this side bet in a moment.)

Once Mozart had finished his variations on the Grétry march, the Grand Duchess stepped forward. Mozart recalled:

“The Grand Duchess produced some sonatas by [Giovanni] Paisiello, which were illegibly written in his own hand. I had to sight-read the [first movement] allegros from them, after which Clementi sight-read the [second movement] andantes and [third movement] rondos. I have it from a very good source that the Emperor was very pleased with me.”

Mozart’s reputation was on the line and he knew it. And he was correct: the Emperor was very pleased with his performance.

Officially, the contest was declared a “draw” and the prize money of 100 ducats was split between Mozart and Clement. The emperor awarded Mozart his 50 ducats and the Grand Duchess awarded Clementi his 50 ducats.

But privately, the emperor collected on his bet with the Grand Duchess. We don’t know how much they bet, but whatever amount it was, it must have galled her no end to admit that Mozart had bettered Clementi.

No doubt Clementi was relieved to have survived his Viennese “trial by fire.” Certainly, he was by far the more gracious of the competitors and gladly admitted to having been entranced by Mozart’s playing. He later wrote:

“Until then I had never heard anyone play with so much spirit and grace.”

Mozart was not nearly so kind to Clementi. A couple of weeks after the duel, Mozart wrote:

“Clementi doesn’t have a Kreutzer’s worth of taste or feeling – in a word, [he is] a mere mechanic.”

Given the musical politics of the time, we suspect that had Clementi been of Austrian descent, Mozart would have managed to find rather more to like about his playing and his music. Though given Mozart’s competitive attitude towards his home turf, perhaps not.