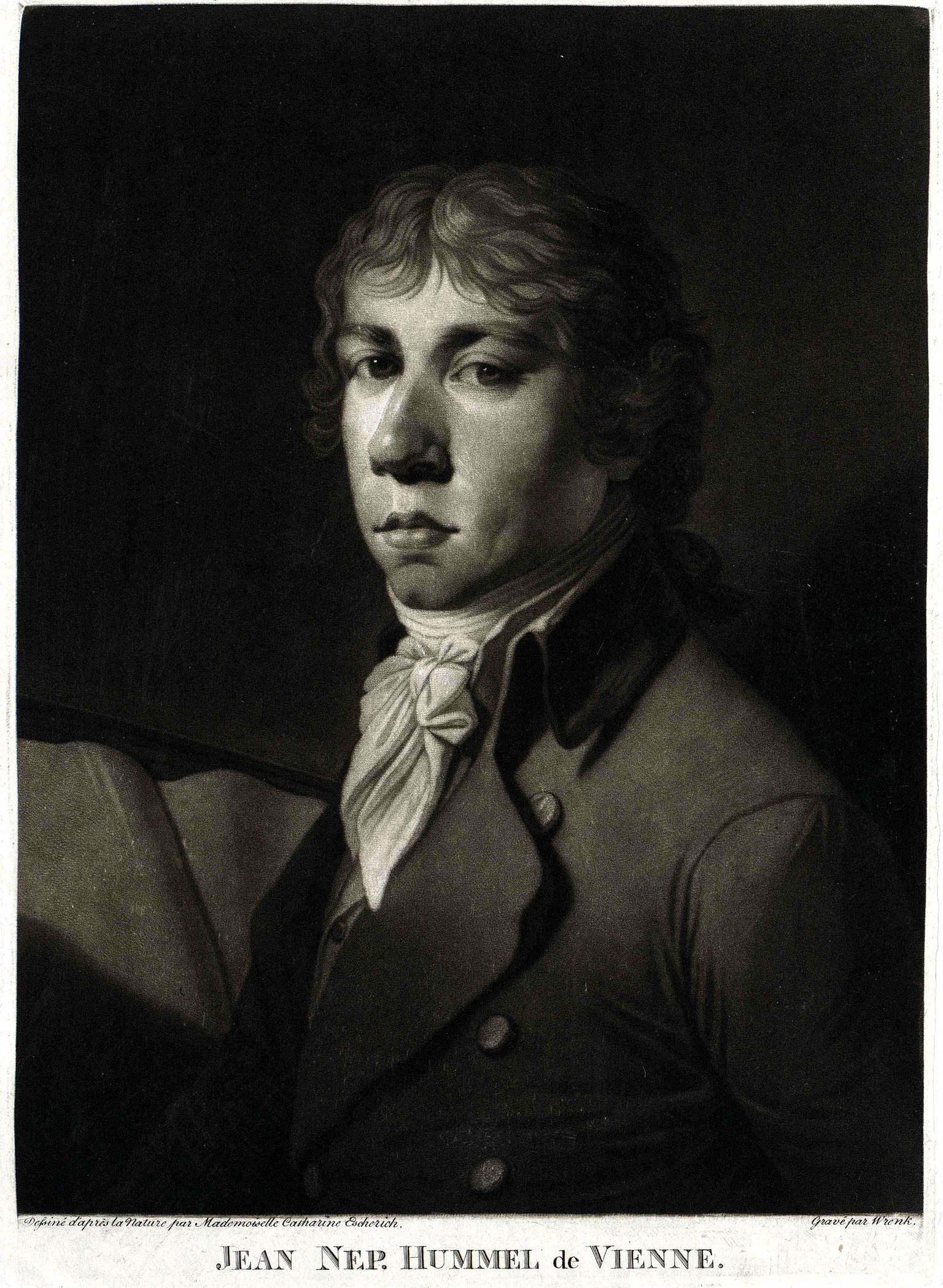

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) was, in his lifetime, considered Beethoven’s equal as a pianist and, if not his equal as a compositional innovator, then a rather more listenable alternative. The former head music critic for The New York Times, Harold Schonberg, put it this way:

“He [Hummel] was a highly regarded composer in his day – overrated then, underrated now.”

A snooty but not inaccurate appraisal. And it is true that as a composer – particularly as a composer of piano music – Hummel remains far underrated today. When his music is discussed, on those fairly rare occasions when it is discussed at all, it is assigned to that strange, in-betweeny netherworld as being “transitional.” In the case of Hummel’s music, it is blithely classified as being “proto-Romantic” or “post-Classical,” as if it were a lesser hybrid (half-breed?) between two otherwise “pure” musical styles, a cross between old music and new music; between the Classical era ideal of the composer as craftsperson and the Romantic era vision of artist-as-hero.

Well, pooh on all of that, and double-pooh on these useless categories so casually bandied about by program annotators and presumed music historians.

As both a pianist and composer, Hummel was far more part of the established mainstream than Beethoven, who was perceived by both his supporters and detractors as an unprecedented compositional maverick (and maniac!).

As a pianist and as a composer for the piano, Hummel’s style of piano playing and composition descended directly from Mozart’s: a pianistic style based on clarity, elegant melody, and expressive subtlety. To this “Mozartean ideal” Hummel added a substantial degree of virtuosity for its own sake. As a pianist, he was an even greater technician than Mozart, and in the increasingly virtuoso-conscience environment of the early nineteenth century, Hummel was happy to put his technique on full display. He was, nevertheless, the last of the great “Viennese” pianists in that he preferred to play the light, not terribly resonant, wooden harped Viennese pianos. As opposed to the bigger and more sonorous metal harped French pianos that were favored by Franz Liszt and Frédéric Chopin and those pianists that followed.

Hummel and Beethoven (1770-1827)

Hummel was Beethoven’s only real pianistic rival during the first decade of the nineteenth century, and he became a favorite for those listeners who found Beethoven’s aggressive, often punishing approach to the piano to be:

“noisy, unnatural, overpedaled, dirty, [and] confused.”

Conversely, Beethoven’s admirers claimed that Hummel’s light, “sweetness of touch”:

“lacked imagination [and was] as monotonous as a hurdy-gurdy and that the position of his fingers reminded them of spiders.”

As we would expect from such arch-competitors, Beethoven and Hummel had an often stormy, on-again/off-again friendship. They were reconciled as Beethoven lay dying in March of 1827, after which Hummel was one of the pallbearers at Beethoven’s funeral. … continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!