Yesterday’s Music History Monday post marked the 77th anniversary of Bartók’s death in New York City, and the circumstances leading to what he himself called his “comfortable exile” in the United States between January 1940 and his death in September 1945. Among the works he composed while living in New York was his Concerto for Orchestra of 1943 which is, by any and every measure, among the very greatest orchestral works composed during the twentieth century. A monumental achievement in and of itself, the fact that the Concerto for Orchestra was written by a composer suffering from leukemia makes it something of a miracle as well. The story of its composition will be told soon enough. But first, indulge me some first-person reflection.

Harlotry in Music

Among my most frequently-asked-questions is: “who is your (my) favorite composer?” Who indeed! My typical response – flippant but true – is that I am a musical harlot, a strumpet, a slut: I love whomever/whatever I’m listening to at the moment. I mean, really: when listening to Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion or the Goldberg Variations, how in heaven’s name would it be possible not to convinced that the sun, moon, and stars revolve exclusively around Bach? For me, the same thing applies when listening to Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro; any Beethoven Symphony; Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov;a Brahms Piano Quartet; Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde; Schubert’s Wintereisse; Haydn’s Creation; Verdi’s Otello; Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto; and a thousand-and-one other works by a hundred-and-one other composers. So much great music; so little time. How can I – or for that matter, any of us – possibly choose a “favorite” among such a wealth of extraordinary work and talent?

On seemingly the same lines, I am also not-infrequently asked, “who is your (my) favorite twentieth century composer?” Now: this is, in fact, a very different question. It’s a different question because starting around the first decade of the twentieth century, the vast majority of young composers began taking it upon themselves to create their own musical languages, partly (if not wholly) divorced from the melodic, harmonic, and formal traditions of seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth century tonal music.

Stylistic and historical differences aside, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and Musorgsky all “spoke” the same musical language, albeit with different accents. When pushed, shoved, and/or entreated to choose a favorite composer among them, we’re endeavoring to choose whose particular use of that common language we prefer over the others. But in choosing a favorite among the composers of the twentieth (and for that matter the twenty-first) century, we’re actually choosing whose particular musical language appeals the most.

I will admit that I am far less promiscuous when it comes to the composers of the twentieth century than I am the composers of the “common practice” (the music of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries). And while I’m generally loath to admit to “favorites”, there are two questions that, once answered, provide the criteria for my choice of a “favorite” twentieth century composer.

Question one: for the sheer, visceral joy of listening, what twentieth century composer’s music would I choose to listen to more often than not?

(This question speaks directly to what I consider the best advice a composition teacher can give to their students: do not write music the likes of which you wouldn’t want to listen to recreationally.)

Question two: speaking personally, as a composer, which twentieth century composer am I most jealous of, meaning: whose music do I wish I had written myself?

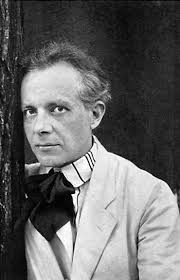

Based on my answers to these questions, my favorite twentieth century composer would have to be the Hungarian Béla Bartók (1881-1945).…

Continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!