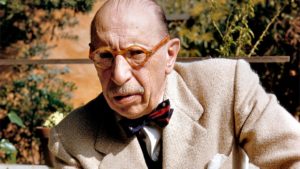

We mark the death on April 6, 1971 – 49 years ago today – of the composer Igor Stravinsky at the age of 88.

To hear him tell it, Stravinsky fully intended to live to be 100 years old. Given the environment in which he grew up, his body, his genetics, and his lifestyle, it was a small miracle that he almost made it to 89. Stravinsky’s long life and remarkably long creative career are together a case of “defying the odds.”

On the plus side, from his young adulthood to very near the end of his life, Stravinsky got up at 8 am and began his day with a regular regimen of calisthenics. He was fit and trim his entire adult life, about which he was quite proud. Sadly, though, when it came to Stravinsky’s health that’s the end of the “plus side” because unfortunately, he did not have genetics on his side. And though he did indeed manage to live into old age, he lived with and through a series of chronic diseases and life-threatening conditions that would have delivered most of the rest of us to an early grave.

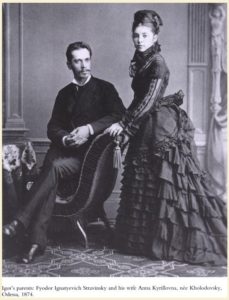

Stravinsky was a life-long hypochondriac, a condition he came by honestly. He was a tiny and frail child. Always self-conscious about his height, he grew up to be a diminutive and physically frail adult, topping out at just 5’3” tall. Growing up in St. Petersburg, Stravinsky received his hypochondria directly from his mother Anna, who was inordinately fearful for the health of her children, particularly the teensy Igor. Stravinsky’s sister Tamara recalled that when she and Igor went out during the winter, her mother would issue a series of injunctions:

“not to go on the ice, not to play with stray dogs, not to talk when out, and to breathe through the nose.”

Stravinsky himself later recalled that:

“I was allowed out-of-doors only after my parents had put me through a medical examination, and I was considered too frail to participate in any sports or games when I was out.”

The fears of Stravinsky’s parents – his mother Anna in particular – were well founded. St. Petersburg was in the late-nineteenth century a veritable petri dish of pathogens, including tuberculosis, smallpox, and cholera, epidemics of which struck the city regularly. Both Stravinsky and his older brother Yuri contracted tuberculosis as teenagers, though in neither case did the disease kill them.

Stravinsky’s constitution remained weak throughout his life, and aside from his chronic coughing, colds, influenza, abscesses, bouts of debilitating colitis, bleeding ulcers, and so forth, he suffered any number of other significant illnesses that might – perhaps even should have – put him under.

Stravinsky did his tubercular lungs no favors over the years when he began smoking at about the age of 15. Soon enough he became a heavy smoker, sometimes irresponsibly so, and as such he periodically suffered from acute nicotine poisoning. The first such episode struck in December of 1911, when Stravinsky was 29 years old and living in Paris:

“I awoke in great pain to discover that I was unable to stand or even sit in an erect position. The illness was diagnosed as intercostal neuralgia caused by nicotine poisoning. It was many months in recovering my strength.”

Stravinsky’s serious illnesses stacked up one after the next. Indulge me this following litany, if only to remind us how lucky – relative to Stravinsky’s health – the rest of us are.

In early June 1913, the 31-year-old Stravinsky’s temperature spiked to 106 degrees. Diagnosed with typhoid fever, his recovery is described as having been “painfully and frustratingly slow.”

Along with another debilitating attack of nicotine poisoning, Stravinsky suffered a nasty bout of pleurisy in the spring of 1918 (“pleurisy” being an inflammation of the thin layers of tissue that separate our lungs from our chest wall).

Neither Stravinsky nor his family managed to avoid the Spanish flu pandemic, though gratefully it was not fatal to anyone in the household. Living in Switzerland at the time, the entire clan became sick in October 1918. Stravinsky’s son Theodore recalled:

“Everyone had to take to their beds, and I can still see Father buried under piles of blankets, his teeth chattering, a big beret pulled down over his eyes and in a very bad temper, while my mother staggered around in her dressing gown handing out medicines, infusions and linctuses [cough syrup] to the whole family.”

In 1932, the now 50-year-old Stravinsky suffered from what is described as “a sever liver infection [for which] he had been on a ferocious diet for months.” (One wonders what constitutes a “ferocious diet”? Tyrannosaurus steaks? Pickled wolverine feet? What?)

Are we all feeling better yet about our personal health?

In the spring of 1937, during an American tour, Stravinsky began violently coughing up blood. His tuberculosis – seemingly in check since he was a teenager – was no longer so. The attack was severe, and Igor, poor boy, had to temporarily give up smoking for the first time in 40 years. “It never rains but it pours!” he groused to a friend. (Dude should have been happy he was still alive!)

Sick with the flu every year, Stravinsky developed a severe, life-threatening case of pneumonia in 1951.

On July 23, 1953, Stravinsky was admitted to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where his prostate was removed. The reason for Stravinsky’s prostatectomy is unclear; nowhere in the literature can I find any reference to a diagnosis of cancer. So in consultation with an M.D. (my wife, who although a pediatrician knows her prostates), a diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia – gland enlargement leading to urinary blockage – was the likely cause. Whatever the cause, the now 71-year-old Stravinsky was in the hospital for ten days and laid up for nearly a month afterward.

Here’s one that has nothing to do with Stravinsky’s constitution and everything to do with his meticulous oral hygiene. In May of 1954, while on tour in Switzerland, Stravinsky bought a bottle of mouthwash in a pharmacy in Geneva. He gargled with it and instantly his throat turned to fire and seized up. His pain was such that he had to cancel one engagement and postpose another. As it turned out, the “mouthwash” bottle had been mislabeled: it actually contained formaldehyde. Total bummer, that.

What many believed at the time was the “beginning of the end” for Stravinsky occurred on Tuesday, October 2, 1956. He was in the midst of conducting his Symphony in C in Berlin when, near the end of the first movement, he dropped his hands and stopped conducting. Somehow the orchestra got through the movement, and somehow Stravinsky rallied sufficiently to finish conducting the symphony. But he had had a serious stroke and was told by a doctor that a second one was not just possible but would potentially be fatal. He was admitted to the Red Cross Hospital in Munich, where he remained for five weeks. Against his doctors’ order, the 74-year-old Stravinsky continued to smoke. Well, not after the clinical neurologist Sir Charles Symonds diagnosed a basilar stenosis (a narrowing of the arteries in the base of the skull) and told Stravinsky that he believed a second stroke was imminent and, if so, it would be fatal. The good doctor told Stravinsky’s wife Vera that the composer would probably be dead in six months and that his health woes were almost certainly the result of a lifetime of excessive smoking.

This is a guy who believed he was going to live 100 years?

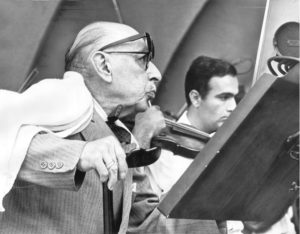

Well, as it turns out, Stravinsky was far from being on his last legs, and in the end got closer to 100 years than anyone thought he would. After having received that diagnosis of stenosis, he quit smoking, went home to Los Angeles, and proceeded to compose a series of experimental, avant-garde masterworks that stand as the capstone to his singular career, among them the ballet Agon (1957); Threni (1958), A Sermon, a Narrative and a Prayer (1961); The Flood (1963); Abraham and Isaac (also of 1963); Variations (1964); and the superb Requiem Canticles (1966), which will be the subject of tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post.

Stravinsky made his last public appearance – in Toronto – on May 17, 1967, after which his body and then his mind truly began to deteriorate, as if the litany of illnesses described up to now was but a warmup.

Stravinsky’s increasingly ill health forced him to move to New York City in October 1969. His first home was a suite at the Essex House at 160 Central Park South, about a block-and-a-half away from where Béla Bartók had lived (and died) 24 years before. Just a week before his death, Stravinsky moved into his last home: a palatial flat at 920 Fifth Avenue at the corner of 73rd Street. It was there that he died – according to his death certificate of heart failure – at 5:20 in the morning on April 6, 1971, 49 years ago today.

Farewell, maestro!

For lots more on Igor Stravinsky, I would draw your attention to my Great Masters biography, The Life and Music of Stravinsky, produced by The Great Courses and available for examination and download.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More