Covid-19 be damned, it’s still Beethoven’s 250th birth year and that celebration stops for nothing and no one, certainly not here on the pages of Dr. Bob Prescribes. Let us then continue to revel in some of Beethoven’s lesser-known works and lesser-known performances.

Today’s Dr. Bob Prescribes is the third and final post to be dedicated to Beethoven’s songs, which together constitute the most under-appreciated segment of his entire output. (Instead of the word “output”, I was about to write oeuvre, which is French for “the collected works of a painter, composer, or author.” But I’ve decided that an English language post shouldn’t refer to a German’s compositional output using a French word. Which immediately brought to mind – as I sure it does for you as well – Henry Watson Fowler’s injunction against using French words in his wonderful A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, Oxford, 1926, which can actually be read for pleasure so entertaining are the entries. Here’s what Fowler [1858–1933, the so-called “Warden of the English Language”] writes:

“FRENCH WORDS. Display of superior knowledge is as great a vulgarity as display of superior wealth – greater, indeed, inasmuch as knowledge should tend more definitely than wealth towards discretion and good manners. That is the guiding principle alike in the using and in the pronunciation of French words in English writing and talk. To use French words that your reader or hearer does not know or does not fully understand, to pronounce them as if you were one of the select few to whom French is second nature when he is not of those few (and it is ten thousand to one that neither you nor he will be so) is inconsiderate and rude.”

Mais oui: exactement!)

Back, please, to where we were before I distracted myself.

Today’s Dr. Bob Prescribes is the third and final post to be dedicated to Beethoven’s songs. The previous posts, which dealt with Beethoven’s early-to-mid-career songs and his folk song arrangements, appeared, respectively, on December 31, 2019 and February 25, 2020. Today’s post will examine Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (“To the Distant Beloved”), Op. 98 of 1816. Not only is it Beethoven’s greatest composition for solo voice, it is also among the most autobiographical works he ever composed.

Here’s its story.

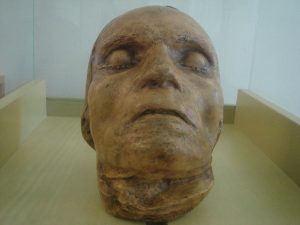

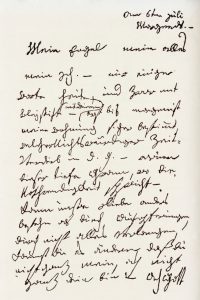

After Beethoven’s death on March 26, 1827, his assistant Karl Holz, his friend Stephan von Breuning, and his brother Nikolaus Johann were sifting through the mountain of papers and other assorted merde (pardon my French!) he left behind looking for bank shares. It was Karl Holz who found it: a copy of a long love letter unlike any other of Beethoven’s thousands of surviving letters. It is filled with spontaneity, passion, exaltation, and confusion. That confusion aside, what the letter makes clear is that Beethoven – probably for the first and only time in his life – had fallen in love with a woman who returned his love.

The letter was written across the span of two days, July 6 and 7. It is the only surviving evidence of a relationship that had been going on for an unknown length of time.

There are two problems with this letter. There’s no year in its date (it says only “July 6 and 7”) and nowhere in the letter does it say to whom it was addressed! In the course of the letter, Beethoven refers to its recipient as his “Immortal Beloved”, and that’s how historians referred to both her (yes, she is a “her”) and the letter itself for over 150 years.

The speculation as to when and to whom the letter was written went on until 1977 when, thanks to the detective work of Maynard Solomon, it was revealed that Beethoven’s “Immortal Beloved” was Antonie Brentano (born von Birkenstock; 1780-1869).

Antonie, or “Toni” von Birkenstock was born in Vienna of the nobility; she was ten years Beethoven’s junior. In 1798, at the age of 18, she moved to Frankfurt, having married a prominent businessman from that city named Franz Brentano. At 33, he was fifteen years her senior.

She returned to Vienna for three years: from 1809 to 1812. In May of 1810 Antonie met Beethoven when she accompanied her sister-in-law Bettina on a visit to the composer. Over the next two years, Antonie and Ludwig developed what Antonie later called a “tender friendship.”

So: what happened between Toni and Louis and when did it happen?