We would recognize a number of date-worthy events before moving on to the admittedly painful principal topic of today’s Music History Monday.

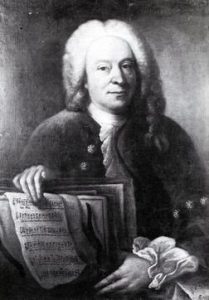

Johann Christoph Graupner

We recognize the birth on January 13, 1683 – 337 years ago today – of the German harpsichordist and composer Johann Christoph Graupner in the Saxon town Kirchberg. (He died 77 years later, in Darmstadt, in 1760.) Herr Graupner was known as a good and conscientious man, highly respected by his employers and students alike. He was also a competent and prolific composer, with more than 2000 surviving works in his catalog. Nevertheless, he would be totally forgotten today but for a single event in 1723.

In 1722, Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) – the chief musician for the churches and municipality of Leipzig – went on to that great clavichord in the sky. The famous Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767), unhappy with his salary in Hamburg, applied for and was offered the job in Leipzig. But it was all a ploy to leverage a higher salary in Hamburg, which he received and where he remained. In early 1723, the paternal units of Leipzig then offered the job to Graupner, who accepted but whose boss – the Landgrave Ernst Ludwig of Hesse Darmstadt – refused to release him from his contract. Then the Leipzig authorities asked the violinist and composer Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688-1758) to apply for the job but having done so, Fasch had second thoughts and withdrew his application. Finally, with no other viable candidates in sight, the authorities in Leipzig grudgingly offered the job to their distant fourth choice: a keyboard and violin player and composer with a (well deserved) reputation for insubordination named Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Bach took the job and stayed on the job for the remaining 27 years of his life.

Why then do we remember Johann Christoph Graupner? Because he was the second choice for a job for which Sebastian Bach was the fourth choice.

Ferdinand Ries

We mark the death on January 13, 1838 – 182 years ago today – of the German composer Ferdinand Ries at the age of 53. Ries composed some 200 works, including 8 symphonies, 8 piano concerti, a violin concerto, 3 operas and 26 string quartets. But it is not for his music that Ries is remembered but rather, for his association with Beethoven. Ries was Beethoven’s student and later, his secretary. But most of all, he was Beethoven’s friend, someone whose reminiscences of Beethoven stand as the single most indispensable first-person account of the great man that has come down to us. For which we are forever in Herr Ries’ debt.

Richard Wagner

On January 13, 1882 – 138 years ago today – the German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) put the finishing touches on the words and music of his final music drama, Parsifal. Never, in the long and storied history of Western music, has music more sublime and glorious been appended to words more vile and grotesque than in Parsifal. For a complete explanation of that statement I would humbly implore you to listen to or watch my Great Courses survey, The Music of Richard Wagner.

The Accordion

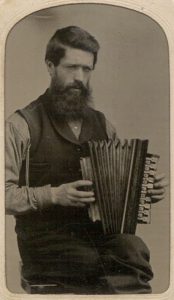

Finally, on January 13, 1854 – 166 years ago today – a Philadelphia-based inventor named Anthony Foss received a patent for the accordion. Also known in English as a squeezebox and a squashbox, Foss did not invent the thing; the first instrument we would recognize as an “accordion” was built and patented as the “Handaeoline” in 1822 by a German named Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann (1805-1864). Foss didn’t even invent the name “accordion”; the term was first used by an Austrian named Cyril Demian (1772–1847), who patented an instrument he called an “accordion” in 1829. But Foss’ patent – for a box-shaped bellows with a chromatic keyboard on one side and buttons for playing harmonies on the other – was close to what we consider a modern accordion, and thus do we honor him today. (Or dishonor him, as it has been suggested that having patented his accordion on January 13, 1854, Anthony Foss’ neighbors began plotting his death on January 14, 1854.)

I have a dear friend who reads this post – he will remain nameless though he will recognize himself soon enough – who among many other things is a diagnostic radiologist, a highly decorated triathlete (he continues to compete), a father and grandfather and the husband of one of the most beautiful, charming, and accomplished women I have ever met. He is as sweet and loving a human being as any I have ever known, and although he will turn 70 in March, he could pass for someone 30 – THIRTY – years younger. (Yes: if I didn’t know and love him, I would be obligated to hate him.)

But he has a skeleton in his closet about which only his closest friends and family know, which is why discretion demands that he presently remain nameless. It is a skeleton he doesn’t deny; he lives with it and acknowledges it, which I think is healthy, as it’s the sort of thing that could be psychologically ruinous if not faced honestly.

This wonderful man grew up playing the accordion.

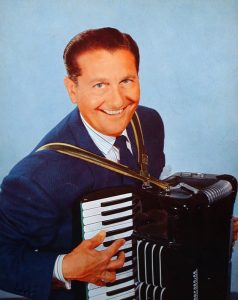

I know; I know: we rightly ask ourselves what sort of parents would do such a thing to a child? But in fairness, we didn’t fully understand the dangers of playing the accordion back then: the devastating social stigma of being associated with the instrument played by Lawrence Welk (1903-1992) and the self-esteem damaging verbal abuse accordion players can be subjected to and the subsequent sense of isolation they can suffer. (We would note that interventive options for children made to play the accordion did not yet exist in the 1960s; Child Protective Services was not created until 1974; and no one had yet created an effective 12-point program for accordionists who just wanted to stop the madness.)

Good heavens: why the stigma? And why the laugh-riot when we see a friend pull out an accordion?

Indeed, laugh-riot: accordion jokes are as plentiful and, if anything, nastier than even viola jokes. Here are a few, provided for our edification and NOT for our amusement.

Q: Why does everyone hate the accordion before even hearing one?

A: It saves time.

Q: What’s the difference between an accordion and a concertina?

A: The accordion takes longer to burn.

Q: How do you protect a valuable musical instrument?

A: Hide it in an accordion case.

This next one is nasty:

Q: What’s the difference between a vacuum cleaner and an accordion?

A: The position of the dirt bag.

Guy leaves his accordion on the back seat of his car on the way to a gig. He runs into the dry cleaner’s to get his tux; he can’t have been gone for more than a minute. On returning to his car he sees – to his horror – that the back window of his car has been smashed in. He looks on the back seat and sees . . . two accordions.

And finally:

Q: How can you identify a gentleman?

A: He is someone who knows how to play the accordion but doesn’t.

How and why did the accordion become the Rodney Dangerfield of musical instruments, “hey, why can’t I get some respect?” And why is the abuse of the accordion a predominately American affliction?

That last joke tells us why, provided we understand the word “gentleman” in its historical context, meaning as a social rank. In England, a “gentleman” was the lowest rank of the landed gentry: a member of the hereditary ruling class, someone well-born, well-heeled, well-bred and genteel. Such a person would never lower himself to play an instrument that was designed for and played by the common person.

There it is: the stigma attached to the accordion is a function of class politics and snobbery, a snobbery that for all of America’s presumed democratization we inherited from our English cousins and, in the case of the accordion, continue to embrace.

Since its popularization in the nineteenth century, the accordion has been known as “the little man’s piano.” And that’s precisely what it is, a one-person band: a relatively inexpensive, portable instrument that could bring music to any venue, indoors or out; in churches, tent meetings, saloons, dance halls, brothels, and played by buskers on the streets. For nineteenth and early twentieth century working class families that had neither the room nor the money for a piano in their parlors, the accordion was the instrument of choice, and it accompanied their singing, their dances, their weddings and family gatherings of every sort.

Part of the problem is that like its wind-driven, reeded cousins the harmonica, the harmonium and the melodeum, the accordion never inspired a critical mass of composers to create a repertoire of its own. Instead, according to Professor Helena Simonett of Vanderbilt University, accordions continue to be linked in the United States with:

“White immigrants, polka music and this kind of low-class image.”

What can I say? I, too, have sinned against the accordion and those who play them. It is a sin I will attempt to expiate by . . . by . . . by hugging an accordionist at my next opportunity, likely my aforementioned friend. In the meantime, as a token of my newly willed good intentions towards the accordion, I offer you the following link to a video of Lawrence Welk, Joey Schmidt, and Myron Floren performing Beer Barrel Polka on the Lawrence Welk Show, recorded in 1981. If you can keep a straight face while watching, wunnerful, wunnerful.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More