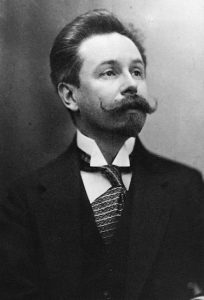

On January 6, 1872 – 148 years ago today – the composer Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin was born in Moscow. He died in Moscow just 43 years later, on April 27, 1915.

Scriabin was not just “the odd person out” of turn-of-the-twentieth-century Russian composers; he was, very arguably, one of the two or three “oddest-people-out” in the history of Western Music.

Scriabin didn’t start out as an oddball. He was a piano prodigy and a friend and classmate of Sergei Rachmaninoff, first in the piano studio and private school of Nikolai Zverov and later at the Moscow Conservatory. When they graduated together in 1892 (at which point Rachmaninoff was nineteen and Scriabin was twenty), Rachmaninoff received the “Great Gold Medal” and Scriabin the “Little Gold Medal”, somehow appropriate given that Rachmaninoff stood 6’6” tall while Scriabin stood just over 5’ tall. (That variance of physical stature notwithstanding, the Moscow Conservatory Class of 1892 was pretty impressive!)

Scriabin’s early career was not marked by any particular “oddness” either. He began his career as a touring pianist and composed charming piano miniatures a la Chopin. He married and quickly fathered four children. When he wasn’t on tour, he taught at the Moscow Conservatory.

Then, in 1902, at the age of 30, something in his mind sparked and fizzled and started giving off smoke. Suddenly pre-occupied with issues philosophical and mysterious, he quit his teaching job, took up with a former student named Tatiana Schloezer, and abandoned his family, telling his wife Vera that he was going to live with Tatiana as “a sacrifice to art.”

I’m not even going to contemplate what would happen to me if I tried that line on my wife.

Depending upon who you talk to, Scriabin went on to become either one of the great visionaries in the history of Western music or a total crackpot. However, the one thing we must all agree on is that Scriabin proceeded to create an extraordinary body of utterly original, intensely lyric, and marvelously crafted music.

Behavioral Issues

Based on even the most cursory reading of the biographical literature, it’s pretty much impossible not to conclude that Alexander Scriabin was a narcissistic egomaniac whose behavior bordered on megalomania. Some writers attribute his developing behavior to mental illness. Others attribute it to overcompensation for his diminutive size (as a pianist, he could not reach more than an octave in either hand and almost ruined his right hand trying to learn to play Mily Balakirev’s virtuosic showpiece Islamey). Still others claim that his narcissism and egomania were the result of his upbringing.

(Scriabin’s mother died of tuberculosis when he was just one year old, and his father, who was a member of the Russian consular service, was posted to Turkey. As a result, according to the English musicologist Hugh Macdonald writing in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians:

“Scriabin was brought up by his aunt Lyubov, his grandmother and his great aunt, all of whom doted passionately on the boy, pampered him endlessly and set his mind towards the fastidiousness and egocentricity of his later years as well as giving him a certain effeminacy in his manners[!].” )

Scriabin spent the years after 1902 contemplating the work that would have been his magnum opus: an apocalyptic, Wagner-inspired, all-inclusive-art-work-on-steroids entitled Mysterium, a massive, no-holds-barred, everything-including-the-kitchen-sink “happening” that would combine:

“All the arts, loading all the senses into a hypnoidal, many-media extravaganza of sound, sight, smell, feel, dance, décor, orchestra, piano, singers, light, sculptures, colors, visions.”

Scriabin planned the work’s premiere for a yet-to-be built, hemispherical temple at the base of the Himalayas. (In order to prepare himself for his sojourn to India, Scriabin went so far as to buy himself a pith helmet, a white tropical suit, and a book on Sanskrit grammar!)

Scriabin intended for Mysterium to be performed over a period of seven days:

“Bells suspended from clouds would summon spectators. Sunrises would be preludes and sunsets codas. Flames would erupt in shafts of light and sheets of fire. Perfumes appropriate to the music would change and pervade the air, and the world would dissolve in bliss.”

According to Scriabin, the climax of Mysterium would bring about nothing less than the virtual collapse of the universe, after which men and women would be reborn as androgynous astral souls, relieved not only of their sexual differences but of any other physical “limitations” as well.

For himself, Scriabin claimed that:

“I shall not die; I shall suffocate from ecstasy after Mysterium.”

To which we might respond, Koo-koo-ka-choo.

Scriabin was pretty much the only Russian composer to take Wagner seriously, and there’s no doubt that when it came to Mysterium, he wanted to “be like Dick” (if not also, pardon-moi, “be a dick like Dick”). But in fact, Scriabin’s plans for Mysterium – never realized, incidentally (surprise!) – made Wagner sound like a small-time carnival barker by comparison.

Seeing Things

A brief sidebar. Much has been made about Scriabin’s color “synesthesia”, a condition whereby Scriabin purportedly saw colors while listening to music. Scriabin had a lot of issues, but synesthesia was not one of them. Scriabin’s “color system” – which associated certain colors with certain pitches – was a carefully worked out system based on the circle of fifths and the primary colors otherwise known as “ROY G. BIV”: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. In Scriabin’s system, “C” was red; “G” (a fifth above) was orange; “D” (a fifth above “G”) was yellow; “A” was green, “E” was blue; “B” was indigo; and “F#” was violet. The remaining five pitches described shades of purple progressing to rust, leading back to the red of the pitch “C” (What? No Taupe?). The point: Scriabin’s “color” system was a purely intellectualized one, invented so that in the course of a musical performance, colors could be projected that corresponded with the pitches being heard. To this end he worked with an inventor named Alexander Mozer to create a “color organ” which, like so many of Scriabin’s best laid plans, never quite worked.

By the last five years of his life – 1910-1915 – Alexander Scriabin had begun to identify rather more with God than with mere mortals. He kept diaries and notebooks in which he’d jot down his thoughts in a sort of “poetic prose”, writing things that would seem to indicate that his driveway no longer went all the way to the street. For example:

“I am freedom, I am life, I am a dream, I am weariness, I am unceasing burning desire, I am bliss, I am insane passion, I am nothing, I am atremble;

I am the world.

I am insane passion, I am wild flight, I am desire, I am light, I am creative ascent that tenderly caresses, that captivates, that sears, Destroying, Revivifying. I am raging torrents of unknown feelings, I am the boundary, I am the summit. I am nothing.

You, depths of the past born from the rays of my memories, and you, heights of the future and creations of my dreams! You are not you.

I am God!

I am nothing, I am play, I am freedom, I am life. I am the boundary, I am the peak.

I am God!

I am the blossoming,

I am the bliss,

I am all-consuming passion, all engulfing,

I am fire enveloping the universe,

Reducing it to chaos.

I am the blind play of powers released.

I am creation dormant, Intellect quenched.”

Look, I’ll be the first to admit that very few of us would want our private journals to become public after our deaths. But we would observe that diary entries like the one I just read do not just reflect Scriabin’s “private thoughts” but are also typical of the sort of things he said in public.

The issue of Scriabin’s mental health broaches a key question. Was the ongoing development of his Messianic megalomania the necessary precondition for the sublime, amazing, and often revolutionary music he composed during the second half of his life?

Like Beethoven’s hearing disability, did mental health issues “free” Scriabin from the musical and social strictures of his time, thus allowing him to find a voice and inspiration within him that he would never otherwise have heard?

The musicologist and Scriabin scholar Hugh Macdonald offers us this irresistible point-of-view on Scriabin’s late music:

“There is clearly a close relation between the egomania of Scriabin’s personality and the singularly direct development of his music from the derivative, charming style of his youth to the powerfully progressive works of his last years; but the weaknesses of his character – his capacity for self-delusion, his overbearing demands on others, and his undisguised conceit – are not to be imputed as weaknesses to his music. The characteristics of a spoilt child were the result of his unusual upbringing, and his compulsive interest in theosophy and mysticism was shared by many at that time, particularly in Russia. Scriabin believed in the coming regeneration of the world through a cataclysmic event, [and that] the new Nirvana would spring from his own Promethean creativity. He even welcomed the outbreak of [World War I] in 1914 as an initial step towards cosmic regeneration.”

(One wonders, had Scriabin lived past 1915, if he would have continued to “enthusiastically embrace” the war, especially given its outcome in Russia: the Revolution and the complete destruction of the aristocratic class and its pretensions that Scriabin held so dear!)

Scriabin’s Death

For someone who came to consider himself nothing less than a creative god, one whose music would bring an end to the universe as we know it and effect the transition to Nirvana, Scriabin’s death could not have been more absurdly prosaic. On Saturday, April 18, 1915 Scriabin noticed a little pimple just above the upper right side of his lip. According to one writer, “The pimple became a pustule, then a carbuncle and again a furuncle.”

Meaning a deep folliculitis: an infection of the hair follicle, most probably caused by the bacterium staphylococcus aureus.

Whatever we choose to call the zit, in less than a week – on April 24 – Scriabin was bedridden with a fever of 106o. In those days before antibiotics, he was as good as dead. (When Scriabin realized that he was dying he cried out, “This is a catastrophe!”) Attempts to drain the infection only made things worse, and he died of septicemia – blood poisoning – at 8 am on April 27, 1915. When the sculptor Sergey Merkulov arrived to make the death mask he could not, so swollen and scarred was Scriabin’s face. So instead he made a cast of his right ear and hand.

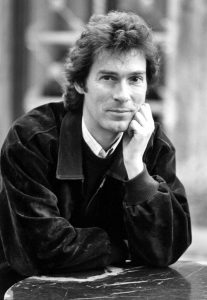

Something to look forward to: tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post – which can be accessed at patreon.com – will feature Bernd Glemser’s superb recording of Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 5 of 1907. All together, Scriabin composed ten numbered piano sonatas. Written across the span of his all-too-brief compositional career, these sonatas trace Scriabin’s musical trajectory and are, according to Jonathan Powell writing in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, “arguably of the most consistent high quality since [the piano sonatas] of Beethoven.”

Until tomorrow!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More