Barbara Strozzi, Amor domiglione (“Sleepyhead Cupid”, 1651); Molly Netter, soprano; Avi Stein, harpsichord; and Ezra Seltzer, cello

We mark the death on November 11, 1677 – 342 years ago today – of the composer and singer Barbara Strozzi at the age of 58. Madame Strozzi saw eight volumes of her music published in her lifetime, making her the most extensively published composer of her time.

Barbara who?

Fame and memory are fickle, to say the very least. It takes very little time for us to forget people who were even recently front-page important. Quickly, off the tops of our heads, who were the vice-presidential candidates on the losing tickets going back to 2000? Who ran with Al Gore? John Kerry? Mitt Romney? Hillary Clinton? (Yes, we remember John McCain’s 2008 running-mate Sarah Palin, but for all the wrong reasons.)

(For our information, those recent vice-presidential candidates were, respectively Joe Lieberman, John Edwards, Paul Ryan, and Tim Kaine, respectively.)

Fame and memory are fickle, often most unfairly so. Certainly, that is the case with Barbara Strozzi, who was a prolific composer of the highest quality working – with some success – in what was most definitely a man’s world. Hers is a fascinating story.

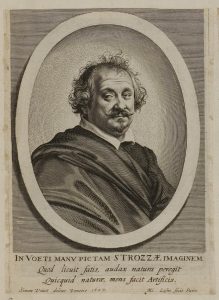

She was born “Barbara Valle” in 1619 in Venice, the illegitimate daughter of a woman named either Isabella Griega or Isabella Garzoni who went by the nickname of “La Greghetta.” Admittedly, when a woman goes by such a nickname – particularly in a place like Venice, which was the Bangkok and Las Vegas of its time – we generally assume that she makes her living, well, you know, on her back. But La Greghetta was, in fact, a domestic servant in the employ of the poet and librettist Giulio Strozzi (1582-1652). Strozzi was the real deal whose opera libretti were set by, among many other composers, Francesco Cavalli and Claudio Monteverdi. Giulio Strozzi was almost certainly Barbara’s father; he referred to her as his “adoptive daughter”; she and her mother lived in his home; and at the age of 18, Barbara took the name Strozzi as her own.

It was Giulio Strozzi who recognized and cultivated Barbara’s extraordinary talent as a singer and a composer. Guilio arranged for her to take lessons in both voice and composition, the latter with one of the most important composers of the time, Francesco Cavalli (born Pietro Francesco Caletti-Bruni; 1602-1676).

For Barbara Strozzi, it was a prescription for success. Growing up in what was then the opera capital of the world, in the house of a famous librettist, surrounded by and hobnobbing with singers and composers and studying with the best of them, Barbara developed rapidly. When she was 15, she was described as being “la virtuosissima cantratrice di Giulio Strozzi”: “the virtuosic singer of Giulio Strozzi.”

Barbara’s first publication – of an eventual eight – is a volume of madrigals appropriately entitled Il primo libro de’madrigali (“First Book of Madrigals”). Published in 1644 when she was 25 years old, the volume contains madrigals for two to five voices set to texts by her father, Giulio Strozzi. That she was acutely aware of the special challenges of being a woman composer is made explicitly clear in the preface, in which she wrote:

“Being a woman, I am concerned about publishing this work. Would that it lie safely under a golden oak tree and not be endangered by swords of slander which have already been drawn to battle against it.”

Her talent notwithstanding, given the time and place in which she lived, there was no way Barbara Strozzi was going to be hired as a court musician or commissioned to compose an opera. And while she earned something from her publications, it was hardly enough to live on. Thus, she did what talented women often had to do in her time and place: she became a professional concubine, the mistress of a married Venetian nobleman and musical patron named Giovanni Paolo Vidman. The depiction of Strozzi in the painting above portrays her dual “professions.” It was painted circa 1639 by Bernardo Strozzi, who may (or may not) have been related to Giulio Strozzi and hangs today at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. Titled Gambenspielerin – “The Viola da Gamba Player” – it does indeed portray a professional musician. But much more, she is a highly sexualized musician. Her amply pendulous bosoms stand (sit? dangle? hang? droop? slump?) almost entirely exposed; she gazes at us frankly and unashamedly, her lips slightly pursed; the skin on her face is flushed pink. (Dearest readers: if a young woman looked at any of us that way and in that state of undress, I think we’d know precisely what she had in mind. Then again, perhaps I just have that sort of mind.)

Barbara Strozzi had four children with her master Giovanni Paolo Vidman; two daughters (named Isabella and Laura) and two sons (Giulio and Massimo). Both Isabella and Laura joined a convent and Massimo became a monk. (Lucky Giulio; when his mother passed away 342 years ago today, he was the only one of her children who could inherit her estate which was, by that time, not insignificant.)

Of her eight published volumes of music, only one – volume 5 (and therefore, Op. 5) of 1655 – contains sacred music. All the other surviving volumes (volume 4 has been lost) contain secular vocal music. Aside from the madrigals in volume 1, this secular music consists of arias, ariettas (short arias) and cantatas (meaning works featuring declamatory and lyric music, meaning recitative and aria); all of them composed for solo voice (mainly soprano) and continuo (meaning a harpsichord or fretted instrument in accompaniment). A few of the works call for strings as well.

The music in these arias, ariettas, and cantatas is melodically lush, intensely lyric, often humorous, and utterly captivating. (I was also going to use the word “fetching” but I’ve always found that word a bit precious, don’t you think?) Strozzi’s vocal lines are wonderfully suited for a lyric soprano; they are neither unduly virtuosic nor do they plumb a particularly wide range. According to Ellen Rosand and Beth Glixon, writing in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians:

“The similarity in vocal style among Strozzi’s works, the scoring for soprano and continuo, and the frequent puns on her name in the texts suggest that she sang most of her music herself.”

(For our info: in her lifetime, Strozzi was almost as well-known as a poet as she was a musician; most of her texts starting in volume 2/Op. 2 are of her own creation.)

The sheer beauty and nuance of Strozzi’s writing; its range of moods and clarity of expression; and its utter lack of virtuosity for its own sake have led many to observe that more than any other composer – including her own teacher, Francesco Cavalli – it was Barbara Strozzi that was the “heir” of the great Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643). While I ordinarily find such statements a bit irksome (not unlike the work “fetching”), I’d go on the record by saying I’m entirely comfortable with the Monteverdi-Strozzi comparison. We must, however, weep bitter tears that Barbara Strozzi never had the opportunity to compose an opera. Or two.

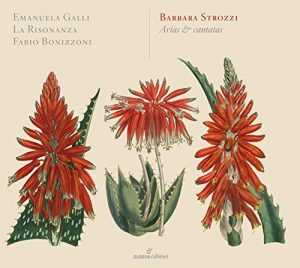

While there are a number of CDs of her music available, no one will ever claim that Strozzi is over-recorded. Taking a page out of my Dr. Bob Prescribes post, I would heartily recommend Strozzi’s Arias and Cantatas, Volume 8/Op. 8 as recorded by Emanuela Galli, soprano; Fabio Bonizzoni, harpsichord; and the ensemble La Risonanza on the Glossa label.

For those who’d like an immediate taste of Barbara Strozzi’s music, I have posted one of her best-known ariettas at the top of this post, an arietta titled Amor domiglione (meaning “Sleepyhead Cupid”) from volume 2/Op. 2, beautifully performed by Molly Netter, soprano; Avi Stein, harpsichord; and Ezra Seltzer, cello.

We miss you, Madame Strozzi, and promise to never again forget you.

For lots more on the music of the Baroque, I would draw your attention to my 48-lecture course How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, published by The Teaching Company/The Great Courses, and available for examination and download at RobertGreenbergMusic.com. I would also encourage you to join me on Patreon, and subscribe to the Music History Monday Podcast.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More