On February 18, 1807 – 212 years ago today – Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23 in F Minor, nicknamed by the publisher the “Appassionata”, was published in Vienna.

The “Appassionata” is one of Beethoven’s most spectacular works, a piano sonata that over the years has evoked some pretty spectacular comparisons: the German-born, American musicologist Hugo Leichtentritt compared it to Dante’s Inferno; the German-born musicologist Arnold Schering likened it to Shakespeare’s Macbeth; Romain Rolland, the French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic (who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915) compared the Appassionata to Corneille’s tragedies; and the English musicologist and music theorist Donald Francis Tovey set it side-by-side with nothing less than Shakespeare’s King Lear.

That’s Sir Donald Francis Tovey, and yes, even Sir Donald – that paragon of English restraint, dignity, and self-control (stiff upper lip and all that rot) – becomes a breathless, idolatrous, Beethoven fan-boy when attempting to describe the expressive content of the Appassionata Sonata:

“This sonata is a great hymn of passion, which is born of the never-fulfilled longing for full and perfect bliss. Not blind fury, not the raging of sensual fevers, but the violent eruption of the afflicted soul, thirsting for happiness, is the master’s conception of passion. In all of Beethoven’s passionate outbursts there is a moral element, a conquest of self, an ethical victory. And this is true, of course, of Opus 57, this deeply personal avowal and one of the most moving documents of a great and fiery soul that humanity possesses.”

Rarely was Beethoven’s “great and fiery soul” more in-our-faces apparent than in late October or early November of 1806, during a visit to his patron Prince Karl Lichnowsky’s country estate near the Bohemian city of Troppau. (“Troppau” is today known as Opava and is located in the Czech Republic.) Despite the fact that Beethoven composed the great bulk of the Appassionata in 1804, it was during this stay at Lichnowsky’s place in 1806 that he applied the finishing touches. The story of that stay must be told, not just for its own sake, but for the light it sheds on Beethoven’s attitude towards his patrons and most importantly, towards himself.

Karl Alois Johann-Nepomuk Vinzenz Leonhard Prince Lichnowsky (1761-1814) was a Chamberlain at the Imperial Austrian Court and a very rich man. He was a friend, Masonic Lodge Brother and patron of Mozart’s. When Beethoven arrived in Vienna in late November of 1792 – almost exactly a year after Mozart’s death – he carried with him a letter of introduction to Prince Lichnowsky written by his hometown patron Count Ferdinand Ernst Joseph Gabriel von Waldstein (to whom Beethoven dedicated his Piano Sonata in C Major Op. 53, appropriately nicknamed the “Waldstein Sonata”).

Beethoven’s letter from Count Waldstein to Prince Lichnowsky was worth its weight in Berkshire-Hathaway stock certificates. It secured him both a small apartment in the attic of Lichnowsky’s magnificent town house in Vienna’s Alstergasse and a patron from heaven.

It is no understatement to say that Prince Lichnowsky fell in love with Beethoven. Within a month Lichnowsky had moved Beethoven into a spacious apartment on the ground floor of his town house. Beethoven began performing at Lichnowsky’s Friday salon concerts, and in the process had the opportunity to meet, perform for, and impress the movers-and-shakers of Vienna’s music scene.

In 1800, Prince Lichnowsky awarded Beethoven an annuity (meaning an annual salary) of 600 florins: roughly $25,000 a year today; not a fortune, but nothing to sneeze at either. Lichnowsky continued to be Beethoven’s principal patron and to pay the annuity until 1806, when the following Appassionata Sonata-related event blew their relationship out of the water.

Here’s what happened

As we previously observed, Beethoven was staying at Prince Lichnowsky’s country estate near the Bohemian city of Troppau in late October or early November of 1806, there putting the finishing touches on his manuscript of the Appassionata. Napoleon’s French army had occupied the area around Troppau after the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, and a number of French officers – including the General in charge of the occupation – were invited by Lichnowsky’s to dine at his country casa. In an effort to ingratiate himself to the French, Prince Lichnowsky foolishly – we might even say stupidly – promised the French General and his officers that after dinner they would have the pleasure of hearing the famous Beethoven – presently a guest, right there, at the castle – play the piano. It never occurred to the Prince to consult Beethoven first, and when Beethoven was informed that he was expected to dine with and play for the French, his gaskets began to pop, one after the other.

Prince Lichnowsky’s personal physician, Dr. Anton Weiser – who was there – reported that:

“They went to the table, and one of the French staff officers asked Beethoven if he also knew the violin. I saw at once how this outraged the artist; Beethoven did not deign to answer his questioner.”

When the time came for Beethoven to play he was nowhere to be found. A search was organized, and Beethoven was eventually located, having locked himself in a distant room of the castle. Through the locked door, Prince Lichnowsky tried to calm him down and convince him to play, but, according to another eyewitness, Ignaz von Seyfried,

“Beethoven was very angry and refused to do what he denounced as ‘manual labor,’ [exclaiming that] he could not play to the enemies of his country.”

Exasperated and utterly mortified, Prince Lichnowsky ordered that the door be broken down. According to Beethoven’s friend and student Ferdinand Ries, Count Franz Oppersdorff (to whom Beethoven dedicated his Symphony No. 4):

“May have made his greatest contribution to Beethoven’s welfare when he threw himself between the two combatants just at the moment when Beethoven picked up a chair and was about to break it over the head of Prince Lichnowsky, who had had the door forced of the room in which Beethoven had bolted himself.”

Beethoven stomped back to his room, threw his stuff into a trunk, and left the castle that night during a storm. Before heading back to Vienna, he wrote a letter to Lichnowsky, in which he famously wrote that:

“Prince! What you are, you are by circumstance and birth. What I am, I am through myself. Of princes there have and will be thousands. Of Beethovens there is only one!”

According to Bigot de Moragues, the Viennese-based librarian for Russian ambassador Count Andreas Razumovsky:

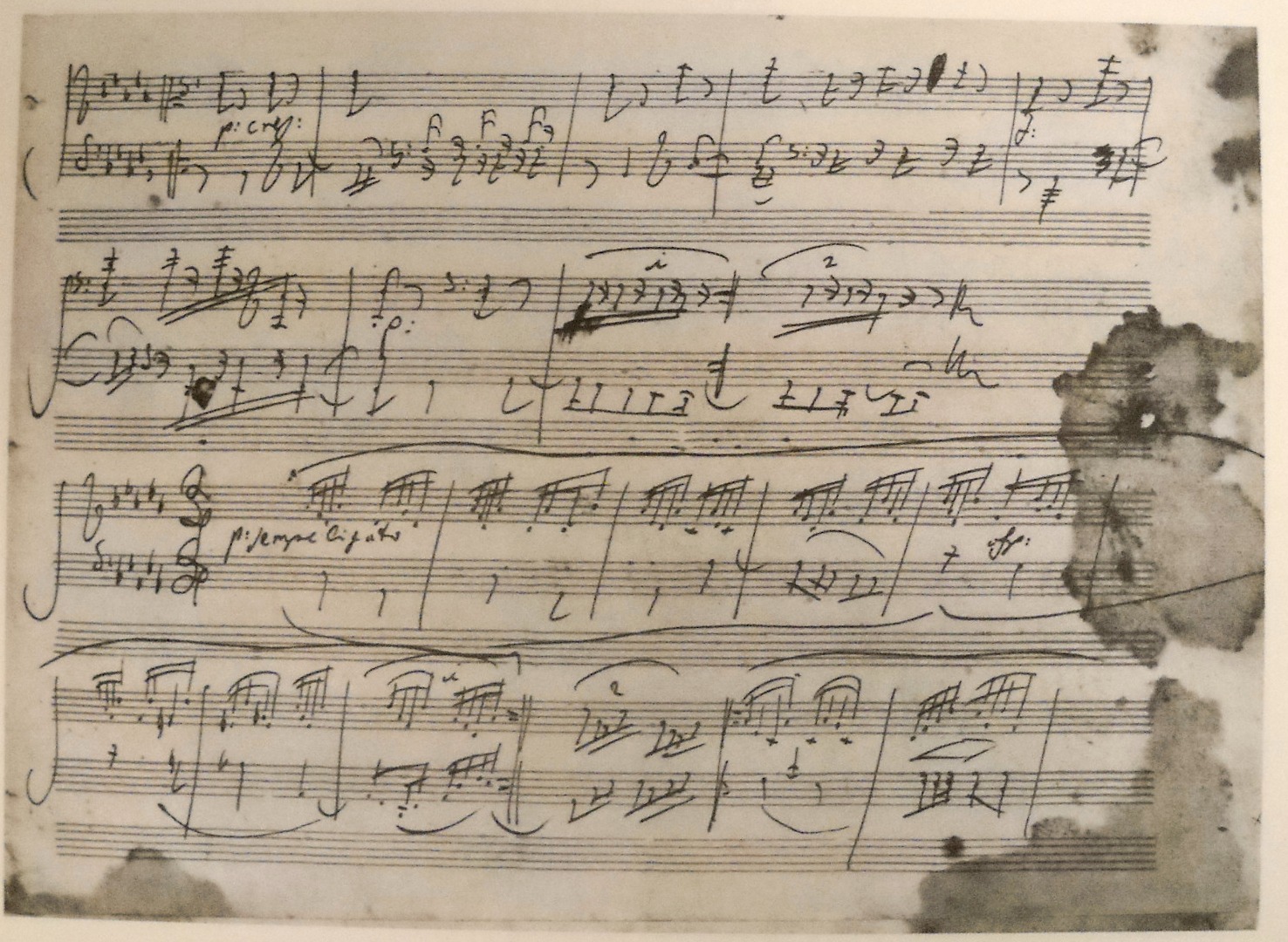

“During his journey [from Lichnowsky’s castle] Beethoven encountered a storm, and pouring rain penetrated into the trunk into which he had the Sonata in F Minor. After reaching Vienna, he came to see us and laughingly showed the work, which was still wet.”

The water stains on the manuscript of the “Appassionata” can be seen to this day.

The cold, wet trip back to Vienna did nothing to cool off Beethoven’s rage. On walking into his apartment, the first thing he did was smash a marble bust of Lichnowsky on the floor. And while Beethoven and Lichnowsky eventually made up, their relationship remained on life-support for the remaining 8 years of Lichnowsky’s life. An immediate upshot – in 1806 – was that Lichnowsky cut off Beethoven’s annuity. For his part, Beethoven no longer considered Lichnowsky worthy of a dedication. Before 1806, Beethoven had dedicated seven works to Lichnowsky, including the Three Piano Trios of Op. 1; the Piano Sonata in C Minor, Op. 13, known as the “Pathétique”; and his Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36. After the evening in Troppau in 1806, Beethoven never dedicated another work to Lichnowsky.

(For our information, Beethoven dedicated the “Appassionata” to Count Franz von Brunswick.)

According to Beethoven biographer Maynard Solomon:

“In later years, Lichnowsky would visit Beethoven in his study, quietly sit watching his protégé at work, and then depart with a brief ‘Adieu’. On occasion Beethoven would lock him out, and the prince, uncomplaining, would descend the three flights of stairs to the street.”

For lots more on Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses surveys: The Piano Sonatas of Beethoven and The 23 Greatest Piano Works.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More