We acknowledge the death – on July 1, 1964, 55 years ago today – of the French-American conductor and teacher Pierre Monteux, who passed away at his home in Hancock, Maine at the age of 89.

Conductors: love them or hate them, we can’t live without them.

Composers and instrumental musicians have mixed feelings about conductors, and rightly so. (I’m leaving singers out of the mix here because it’s been my experience that singers, bless them, will generally do what they damn please, conductor or no conductor.)

As a composer, I can tell you that it is disquieting to hand over a “child of my imagination” – a score – to a conductor. I know that 99% of the time that conductor will do her level best to perform the piece to my specifications, whether she herself “likes” the piece or not. But you never really know what’s going to happen in a performance, and every composer I know has at least a couple of horror stories to tell when it comes to their experience with conductors.

(I had a Concerto for Vibraphone and Chamber Orchestra premiered on a Monday Evening Concert at the Los Angeles County Museum some 25 years ago. The dress rehearsal was a disaster. Now, there is a school of thought that subscribes to the belief that a terrible dress rehearsal means a successful first performance. I myself do not attend that school; merde on Monday afternoon does not usually transmogrify into ambrosia on Monday evening. Anyway, after the dress rehearsal, the conductor – a super guy, really – sheepishly said to me, “Well, we got the shape of the piece!” My response was something on the lines of, “I drop my toddler off at daycare at 8 am. I pick him up at 4 pm. He’s missing an arm; his ears are mangled; a few of his toes are gone and his hair has been torn out. When I ask ‘what happened?!?’ I’m told, ‘well, his shape is still there.’”)

As for musicians, no one likes being told constantly what to do, particularly if it goes against the grain of one’s own experience, and yet that’s exactly what orchestral musicians deal with on a day-to-day basis. And for – say – a 60-year-old professional violinist, who has been there and done that, to be told what to do by a thirty-something conductor the violinist does not respect? That can create a degree of bitterness in the mouth of the violinist that makes apple cider vinegar taste like Hawaiian Punch.

It takes a certain sort of person to want to be a professional conductor; the same sort of person who wants to be a CEO, or a head coach, or a battlefield commander, or for that matter, the President of the United States: someone who both wants to lead and is, at the same time, convinced beyond any doubt of the rightness of his or her thinking. If such an individual is a principled person of sensitivity and intelligence, the inherent megalomania in wanting to always “be-in-charge” will almost certainly be moderated by ethical behavior. But heaven help us when a person-in-charge is unprincipled, insensitive and unintelligent. And while it is unusual in the professional world for such a person to attain a high-leadership role, it is sadly – even tragically – not as rare as we might like to think.

And while such less-than-savory conductors have indeed existed, from here on out, let us dwell not on the negative but rather, on what makes conductorial greatness.

What makes a great conductor?

A great conductor is a musician of the very first rank, able to hear in his head and play at the piano even the most complex orchestral scores. But more than just a top-flight musician, he must be, alternately, a therapist, critic, benevolent friend and tyrant as he rehearses and shapes a work for performance.

Some new age-type conductors even talk today about giving their players ownership of the music. This is a lovely, politically-correct concept, though it is a concept, as every leader knows, that can be taken only so far. The bottom line is that a conductor can neither abdicate nor delegate his or her responsibility: the musical buck must stop at the podium. An orchestra is not a democracy. A great conductor is an enlightened despot who can, to a degree, empower her players without ever surrendering her own power, vision, and responsibility.

Permit me to add to this list of what makes a conductor “great” a few very personal qualifications, qualifications with which not everyone will agree.

One. It has been my experience that the best high school and youth orchestra conductors qualify as great conductors, and here’s why: they must not just lead with a clarity and precision far greater than someone conducting professionals, but they must also teach and at the same time encourage and inspire their student charges. Such a conductor changes lives on a daily basis, and I stand in awe of what they do.

Two. I personally have no patience for abusive, sarcastic, or dictatorial behavior from conductors which, thankfully, has been on the decline since the mid-twentieth century. Color me a candy-derriere, but I do not believe – given the way most people are today – that quality music making can take place in a hostile environment. (The last casual band I ever played in was a combination Top-40/Klezmer[!] quartet called “Hot Borscht.” I hated every minute I was in that band. A primary reason was the drummer, who was a total jerk. At one point I asked him up front why he always had to be such a butt-wipe. His response, after telling me to go eff myself, was that “you don’t have to like someone to play with him.” Au contraire dude, music is love, and I do need to at least “like” the people I perform with. I left that band as soon as I was able to.)

Three. Conductorial greatness requires taking risks and not being afraid of what is new. To me, the most important conductors are those who have both distinguished themselves in the standard repertoire and have, as well, championed new music across the course of their careers.

By every standard – including mine – Pierre Monteux was among the very greatest of conductors.

What an amazing life he led.

Pierre Benjamin Monteux was born in Paris on April 4, 1875, the fifth of six children born into a Sephardic Jewish family.

He began to play the violin at six and was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at the age of 9. (Among his fellow violin students at the Conservatoire were George Enescu, Carl Flesch, and Fritz Kreisler. Whoa.) At the age of 12 he organized and conducted an orchestra of Conservatoire students in order to accompany his friend and fellow student, the pianist Alfred Cortot, in performances of concertos in and around Paris. While he was still a student – from 1889 to 1892 – Monteux played violin in the pit at the Folies Bergère; many years later he told George Gershwin that it was playing the popular dance music at the Folies that forged his rhythmic sensibilities.

In the early 1890s, Monteux joined the Geloso String Quartet – the resident quartet of the Beethoven Society – as a violinist and violist.

He loved to share what Johannes Brahms himself said when the quartet played one of his quartets for him: “It takes the French to play my music properly. The Germans all play it much too heavily”.

(Many years later – while in his seventies – Monteux sat in with the Budapest Quartet and played Beethoven quartets without the benefit of a score or a part. When he was asked by the record producer and pianist Erik Smith if he could actually write out the parts of any one of the Beethoven quartets, Monteux nodded and said, “You know, I cannot forget them.”)

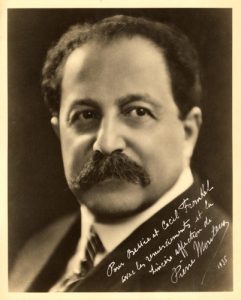

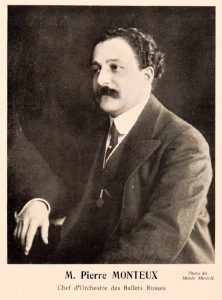

Short, portly, and sporting a walrus moustache, this was the already distinguished musician who began conducting professionally in 1902, when he was hired as an assistant conductor at the Dieppe Casino on the Normandy coast.

Monteux’s break came in 1910. He was, at the time, the principal violist and assistant conductor of a Paris-based orchestra called Concerts Colonne. In 1910, this orchestra was hired by Serge Diaghilev to play in the pit for the second season of his Ballets Russes. Monteux played viola for the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Firebird. In 1911, Stravinsky personally chose Monteux to conduct the premiere of Petrushka, and Monteux’s conducting career was truly launched. Diaghilev appointed him the Principal Conductor of the Ballets Russes. He toured with the troupe and performed, among many other works, Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet version of Claude Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, the world premiere of Debussy’s Jeux, and of Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé.

The event that almost overnight made Monteux a world-famous conductor at the age of 38 occurred on May 29, 1913, when he conducted the first performance of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Monteux had first heard the score as played on a piano by Stravinsky in a tiny rehearsal room in the Théâtre du Casino. Monteux recalled:

“Stravinsky sat down to play a piano reduction of the entire score. Before he got very far, I was convinced he was raving mad. Heard this way, without the color of the orchestra – which is one of its greatest distinctions – the crudity of the rhythm was emphasized, its stark primitiveness underlined. The very walls resounded as Stravinsky pounded away, occasionally stamping his feet and jumping up and down to accentuate the force of the music; not that it needed much emphasis. My only comment at the end was that such music would surely cause a scandal.”

Monteux was correct: the premiere of The Rite did indeed “cause a scandal”. The riot that occurred at that first performance remains among the most legendary events in the history of Western music. The hero of that night was not Stravinsky, who left his seat in a huff (or perhaps a minute-and-a-huff; thank you Groucho); nor was it Diaghilev, who kept flicking the house lights on and off in an attempt to quiet the audience; nor was it the choreographer Nijinsky, who kept shouting numbers (“like a coxswain”, according to Stravinsky) in his futile attempt to keep the dancers together; rather, the hero was Pierre Monteux, who kept going. Stravinsky recalled:

“The image of Monteux’s back is more vivid in my mind today than the picture of the stage. He stood there apparently impervious and as nerveless as a crocodile. It is still incredible to me that he actually brought the orchestra through to the end.”

(For our information, Monteux’s recording of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring with the Boston Symphony Orchestra will be the topic of tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post.)

Thanks to that premiere performance of The Rite of Spring, Monteux’s conducting career went into high international gear. He was the principal conductor of French repertoire at the Metropolitan Opera in New York from 1917 to 1919; the Principal Conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1919 to 1924; the “First Conductor” of the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam from 1924-34; a principal conductor of the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris from 1929 to 1938, and the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony from 1936 to 1952.

Monteux had first conducted in San Francisco in 1931. When he was offered the Directorship in 1935, he hesitated: his wife had no desire to live off the west coast of the United States and financial issues had forced the symphony to cancel its entire 1934 season. Nevertheless Monteux – now 60 years old – took the job and, according to the New York Times, his tenure had:

“an incalculable effect on American musical culture, [giving him] the opportunity to expand his already substantial repertory, and by gradual, natural processes to deepen his understanding of his art.”

With the invasion and occupation of France in 1940, Monteux could not return to Paris, and he became a naturalized American citizen in 1942.

In 1961, at the age of 86, he was offered and he signed a 25 year contract to become the Chief Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, which he retained until his death three years later, 55 years ago today, on July 1, 1964.

By every possible standard, Pierre Monteux was a great conductor.

He was a tireless champion of new music as well as lesser-known works by lesser-known composers.

Monteux’s fidelity to “the score” was absolute. In an era when conductors took liberties that would be unthinkable today, Monteux’s conducting, more than even Toscanini’s, was about the score. He wrote:

“Our principal work is to keep the orchestra together and carry out the composer’s instructions, not to be sartorial models, cause dowagers to swoon, or distract audiences by our ‘interpretation.’”

In many ways, Monteux was the “anti-Leonard Bernstein”, the “un-Lennie”, a conductor who simply refused to call attention to himself. In 1957, the music writer and director of the National Arts Foundation Carleton Smith observed:

“His approach to all music is that of the master-craftsman. Seeing him at work, modest and quiet, it is difficult to realize that he is a bigger box office attraction at the Metropolitan Opera House than any prima donna.”

As for teaching and inspiring students, Monteux considered teaching to be, after conducting, his second greatest calling. He wrote:

“Conducting is not enough. I must create something. I am not a composer, so I will create fine young musicians.”

And that he did. He began teaching conducting classes in Paris and Les Baux (in Provence) in the 1930s, where among his students was the great Ukranian-born conductor Igor Markevitch. Among the many student conductors who studied with him privately in the United States were Seiji Ozawa, José Serebrier, Robert Shaw, and André Previn. (Previn called Monteux “the kindest, wisest man I can remember, and there was nothing about conducting he didn’t know.”)

The name-dropping doesn’t stop there. In 1943 Monteux founded what is today known as the Monteux School and Music Festival in Hancock, Maine. Monteux School alums include Leon Fleisher, Erich Kunzel, Lorin Maazel, Neville Marriner, and David Zinman.

Finally, unlike that un-named drummer from “Hot Borscht” and many of Monteux’s fellow conductors, Monteux was beloved by the musicians that worked with him. The pioneering record producer for Decca Records John Culshaw described Monteux as being:

“that rarest of beings – a conductor who was loved by his orchestras. To call him a legend would be to understate the case.”

Well, we’re not understating the case. To you Maestro Monteux, on the anniversary of not your death, but the conclusion of a long and extraordinary life, well-lived.

Please: for more blogs, vlogs, reviews and rants, join me on my Patreon channel at Patreon.com/RobertGreenbergMusic.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More