We mark the first performance on March 9, 1842 – 178 years ago today – of Giuseppe Verdi’s third opera and first operatic masterwork, Nabucco, at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

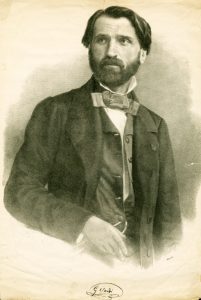

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813-1901) was born on either the ninth or tenth of October 1813, in the north-central Italian village of Le Roncole in the Duchy of Parma. At the time, the Duchy of Parma was part of Napoleon’s “First French Empire” and as such Verdi’s birth name was recorded in French as “Joseph Fortunin François”. Thus, this great Italian patriot was born– much to his later annoyance – as a citizen of France.

Verdi’s family moved to nearby Busseto when he was still a child, and it was there that Verdi acquired the padrone – the patron – who would shape his life: a wealthy merchant named Antonio Barezzi. Barezzi paid for Verdi’s musical education, arranged for Verdi’s first full-time music position (as Busetto’s “town music master”), and sponsored Verdi’s first public performance. But even more, Antonio Barezzi “gave” Verdi the greatest gift any father can give, and that was the hand of his daughter Margherita; the two were married on May 4, 1836. Margherita in turn quickly gave Verdi two children, a girl – Virginia Maria Luigia (born in March 1837) and a boy Icilio Romano (born in July, 1838).

Life was not kind to Giuseppe and Margherita Verdi. Both children died: Virginia of some unknown malady at the age of 16 months and Icilio of bronchial pneumonia at the age of 17 months. Verdi later wrote that:

“The poor little boy, languishing, died in the arms of his utterly desolate mother.”

Buried in grief and debt, Verdi and Margherita gamely struggled on.

On November 17, 1839, just a few weeks after his son Icilio’s death, Verdi’s first opera – Oberto – received its premiere at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, then as now the most prestigious opera theater in Italy.

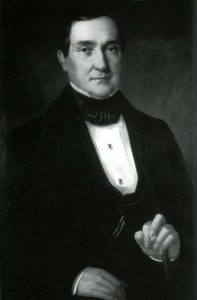

The reviews of Oberto ranged from so-so to very good. However, the most important review didn’t appear in the papers; it was the evaluation of Oberto made by La Scala director Bartolomeo Merelli. So impressed was he that the morning after the premiere he made Verdi an offer no one could refuse. Verdi remembered Merelli’s offer as being:

“lavish at that time: he offered me a contract for three operas to be written at eight-month intervals, to be performed at either La Scala or in Vienna, where he was also the impresario; in return he would pay me 4,000 Austrian lire per opera, [and split] the profit from the sale of the scores half and half with me.”

So there you have it: by late November 1839, Verdi had an opera on the boards, a contract and a publisher. Giuseppe and Margherita, each 26 years old, assumed that the bad times were behind them. And who could blame them if they thought so? Verdi had a three-opera contract. They could pay off their debts. And though they grieved for their children, they were still young and assumed they would have more.

I wish I could tell you that they were right, but sadly, I cannot.

Verdi began work on his next opera, the first of the three operas contracted by Merelli, a comedy entitled Un Giorno di Regno, “King for a Day”. A few months later, in June of 1840, Margherita suddenly became ill. While the illness was diagnosed as rheumatic fever, it was probably encephalitis. She died there in Milan on June 18, 1840.

Verdi was despondent:

“A third coffin went out of my house. I was alone. Alone! In the space of [22 months] three loved ones had disappeared forever. I no longer had a family. And in the midst of this terrible anguish, I was compelled to write and finish a comic opera!”

Verdi returned to Busseto and collapsed. According to Verdi’s friend Giuseppe Demalde:

“His profound sorrow led him to give up everything completely and forever. He thought of nothing but hiding himself in some dark corner and living out his miserable existence.”

The magnitude of Verdi’s grief and rage were such that his friends and family were concerned for his sanity. For his part, Verdi wrote Merelli to tell him that he would not be returning to Milan and that he would not finish the opera. But the opera had been announced and the rehearsals scheduled, and Merelli, may he be blessed forever, dug in his heels and refused to let Verdi out of his contract. A broken man, the 27-year-old Verdi dragged himself back to Milan, went back to the little apartment he and Margherita had so recently shared and finished composing this “comic opera” in a little under six weeks.

Un Giorno di Regno – “King for a Day” – was premiered on September 5, 1840, and it was a flop; some of the numbers were applauded, but others were whistled at and booed. It was, for Verdi, an excruciating, humiliating evening, one he never, ever forgot. Twenty years later, still stinging with hurt, Verdi wrote:

“[The audience] abused the opera of a poor, sick young man, harassed by the pressure of the schedule and heartsick and torn by horrible misfortune! Oh, if the audience had – I do not say applauded but had borne that opera in silence – I would not have had the words to thank them. Today, I accept the public; I accept its whistles on the condition that I am not asked to give back anything in exchange for its applause.”

The morning after the premiere of Un Giorno di regno, Merelli called Verdi into his office. Verdi later said he expected to receive a full blast dressing-down, but Merelli, bless him once again, encouraged Verdi to take heart. The remaining performances of Un Giorno were cancelled, and in their place Merelli remounted Verdi’s first opera – Oberto – which received an additional 17 performances, performances that were cheered by the very same Milanese audiences that had just hissed Un Giorno.

Nabucco

As far as Verdi was concerned, the audience could take those cheers and put them where the sun didn’t shine. In December of 1840, he announced he was through with music, finito. A day or two later Verdi ran into Bartolomeo Merelli on the street there in Milan. If we are to believe Verdi’s account of the story – and there’s no reason why we shouldn’t – then their “accidental meeting” was one of the most serendipitous moments in the history of music. Verdi recalled:

“Large snowflakes were falling and [Merelli], taking me by the arm, invited me to come with him to the director’s office at La Scala. As we walked along, he told me that he was in a terrible fix because of a new opera he had to present. He had given the assignment to [the composer Otto] Nicolai, who was unhappy with the libretto.

‘Imagine’, Merelli said, ‘a libretto by [Tomisticle] Solera: stupendous, magnificent, extraordinary! Effective dramatic situations; grand, beautiful lines; but that crank of a composer refuses to look at it, saying that it is an impossible libretto!’

We reached the theater. Merelli took a manuscript in his hand and exclaimed:

‘See, here it is! Solera’s libretto! Such a beautiful plot! Imagine turning it down. Take it. Read it.’

‘What the devil do you want me to do with it? No! No! I have no desire to read libretti!’

‘Well it’s not going to bite you’, Merelli said. ‘Read it and then bring it back to me.’ And he handed me a huge sheaf of papers written in big letters, the kind they used then. I rolled it up; and, saying goodbye to Merelli, I went off to my house. I went to my place, and with an almost violent gesture, I threw the manuscript on the table, and stood straight in front of it. The bundle of pages, falling on the table, opened by itself: without knowing why, I stared at the page before me and saw the line ‘Va pensiero sull’ali dorate’ (“Fly, thought, on golden wings”).

(As it would turn out, Verdi’s choral setting of Va pensiero became the unofficial anthem of the “Risorgimento”, the nineteenth century Italian revolt against foreign occupation and oppression. When performed in the opera, the chorus is sung by the Israelites who are being held captive in Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar (in Italian, Nabucco). When the opera was first performed at La Scala and then across Italy, it didn’t take long for audiences to decide that the Israelites’ dream of freedom and homeland was their dream of freedom and homeland as well. Verdi’s chorus almost immediately achieved the status of a national hymn, and to this day it will be sung by Italians at any time, in any place.

Back to Verdi’s recollection of his rebirth:

“I threw the manuscript on the table. The bundle of pages, falling on the table, opened by itself: I stared at the page before me and saw the line ‘Va pensiero sull’ali dorate’, I ran through the lines that follow and got a tremendous impression from them. I read one section; I read another; then, firm in my decision not to compose again, I forced myself to close the manuscript and go to bed. But yes! Nabucco was racing through my head! I could not sleep: I got up and read the libretto, not once, not twice, but three timers, so that in the morning I knew Solera’s whole libretto from memory. In spite of all that, I was still [resolved never to compose again]. The next day I went back to the theater and gave the manuscript back to Merelli.

‘Beautiful, eh?’ he said to me.

‘Very beautiful.’

‘All right, then, set it to music!’

‘Not a chance! I would not even dream of it! I don’t want anything to do with it!’

[Merelli chanted:] ‘Set it to music! Set it to music!’

And, saying this, Merelli took the libretto, stuck it in the pocket of my overcoat, took me by the shoulders, and, with a big shove, pushed me out of his office. Not just that: he closed the door and locked it!

What was I to do?

I went back home with Nabucco in my pocket. One day, one line; one day, another; now one note, then a phrase. Little by little, the opera was composed.”

Verdi finished Nabucco in 10 months, in early October of 1841. Merelli scheduled its premiere for March 9, 1842, at the tail-end of Milan’s Carnival season. The cast featured the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi who, in time, would become Verdi’s second wife. A measly twelve days were scheduled for the rehearsals, hardly adequate for a new work of such monumental proportions. But a remarkable event took place during the rehearsals, and Verdi later claimed that it was at that moment he knew his luck had changed. Verdi:

“The [common] people have always been my best friends, from the very beginning. It was a handful of carpenters who gave me my first real assurance of success.

[It was during a rehearsal.] The [performers] were singing as badly as they knew how, and the orchestra seemed bent only on drowning out the noise of the workmen who were making alterations in the building. Presently, the chorus began to sing, as carelessly as before, ‘Va Pensiero’, but before they had gotten through half-a-dozen bars the theater was as still as a church. The [carpenters] had stopped working one by one, and there they were, sitting about on the ladders and scaffolding, listening! When the number was finished, they broke out in the noisiest applause I have ever heard, crying, ‘Bravo, bravo, viva il maestro!’ and beating on the woodwork with their tools. Then I knew what the future had in store for me.”

When Verdi took his place in the pit to conduct the premiere of Nabucco on March 9, 1842, the cellist Vincenzo Merighi said to him:

“Maestrino [a term of endearment, meaning, literally, “little maestro”], maestrino, I wish I were in your place this evening.”

And well he might have wished, because Nabucco was a triumph. Verdi was called repeatedly to the stage by the ecstatic audience. The reviews were uniformly rapturous. Verdi’s father called it a miracle. Verdi went to bed that night and woke up famous.

What did that opening night audience see and hear that so inspired them? They heard music that was lyric, memorable, magnificent and magnificently wrought, music that spoke, as Beethoven would have said, “from heart to heart”. They saw a powerful opera seria in which the story was a thinly veiled allegory for the state of the Italian nation itself: a proud and ancient people, divided and largely controlled by oppressive foreigners, longing to be free. Nabucco spoke directly to the patriotic heart of the Italian people.

Nabucco immediately earned a place in the operatic repertoire, where it has remained to this day. It received an incredible 75 performances at La Scala alone during the year of its premiere, not counting other performances that took place across Italy.

Of Nabucco, Verdi later wrote:

“With this opera, you can truly say that my artistic career began.”

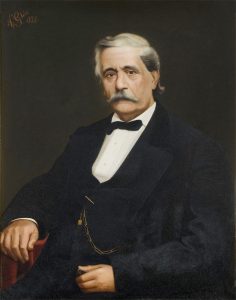

It was a career that would completely dominate Italian opera for the next 59 years!

For lots more on Verdi and Nabucco, I would direct your attention to my Teaching Company/Great Courses survey, The Operas of Verdi, which can be examined and downloaded here at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More