December 2 is – was – a great date for world premieres, as well as for one unfortunate and extremely notable exit.

Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 received its first performance on December 3, 1883 – 136 years ago today – in Vienna, when it was performed by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Hans Richter.

On this date in 1949 – 70 years ago today – Béla Bartók’s Viola Concerto, completed posthumously by Tibor Serly [TEE-bor SHARE-ly] (Bartók himself had died four years earlier, in 1945), received its premiere in Minneapolis, where it was performed by violist William Primrose and the Minneapolis Symphony, conducted by Antal Dorati.

We would note the unfortunate exit, on December 2, 1990, of the composer Aaron Copland. He died at the age of 90 in North Tarrytown (known today as “Sleepy Hollow”), New York, about 30 miles north of New York City.

There’s one more premiere to note, which will occupy the remainder of today’s post. We mark the premiere, in Boston on December 2, 1949 – the same day as the premiere of Bartók’s Viola Concerto – of Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphony, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Bernstein. In my less-than-humble opinion, the symphony must be numbered among the most thrilling and original works composed during the twentieth century, and it will occupy us for two days. This Music History Monday post will discuss Messiaen’s life and the creation of the symphony, and tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post (which can be found on Patreon) will get into the particulars of the piece – which is Messiaen’s one-and-only symphony – and my recommended recording.

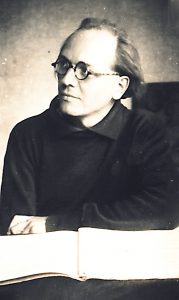

Olivier Messiaen was born in Avignon, France, on December 10, 1908. His mother, Cécile Sauvage, was a well-respected poet, and his father, Pierre Messiaen, taught English. Among Messiaen pere’s accomplishments was having translated the complete works of Shakespeare into French. In such a highly cultured household, Olivier’s musical precocity was recognized early and carefully cultivated. He began composing at the age of seven. When he was ten years old, his harmony teacher, Monsieur de Gibon, gave his precocious young charge a score of the then just deceased Claude Debussy’s one and only opera, Pelleas and Melisande. It was, for Messiaen, a revelation; he later wrote that receiving and then studying the score was:

“Probably the most decisive influence in my life.”

Without any doubt, it was Debussy’s extraordinary and utterly original treatment of harmony, tonality, and rhythm – rhythm liberated from a predictable pulse and the tyranny of the bar line – that inspired Messiaen to even greater tonal and rhythmic freedoms in his own music. If any single composer can be said to be the successor of Debussy – in terms of both musical syntax and sheer originality – it is Olivier Messiaen.

The year after he received that oh-so-important score of Pelleas and Melisande, the eleven-year-old Messiaen entered the Paris Conservatory. He put the place on its ear, truly; I have been told that they still talk about him at the Conservatory to this day, so amazing was his tenure there. In 1926, at the age of 18, he won first prize in harmony, counterpoint, and fugue. In 1928, he won first prize in piano accompaniment. In 1929, he won first prize in music history. And in 1930, the year he graduated, Messiaen won the prize he coveted most of all: first prize in composition.

Upon graduating in 1930, Messiaen was appointed organist at La Trinite in Paris, a post he held for forty years – until 1970! In 1936 – at the age of 28 – he joined the faculty of the Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris. Three years later, in 1939 – at the age of 31 – Messiaen joined the French Army as a medical orderly after Germany invaded Poland and France subsequently declared war on Germany.

Joining the French Army in 1939 was the right thing to do, the patriotic thing to do but, as it turned out, it was like buying stock in Lehman Brothers on the morning of September 15, 2008 (a few hours before its sudden bankruptcy), it was not the smart thing to do. The “Battle of France” (better called the “Fall of France”) lasted for all of six weeks. Nazi Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940; France’s surrender, signed on June 22, 1940, went into effect on June 25.

Messiaen was taken prisoner in May of 1940. He spent the next two years in Stalag VIIIA in Gorlitz, in Silesia. (It was there – as a prisoner of war at Stalag VIIIA – that Messiaen composed his Quartet for the End of Time for clarinet, violin, ‘cello, and piano. Messiaen dedicated the quartet “in homage to the Angel of the Apocalypse, who raises his hand towards Heaven saying, ‘There shall be no more time.’” It was first performed at the camp on January 15, 1941, in an unheated space in Barrack 27.)

Messiaen was freed and repatriated in 1942. He returned to Paris, where he was appointed professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatory. On top of his duties at the Conservatory, he began teaching private composition classes in 1943 at the home of a friend named Guy Delapierre. Among the student who attended these private classes was the pianist Yvonne Loriod, who would eventually become Messiaen’s wife and who would play a pivotal role in the creation of the Turangalîla Symphony, and a young Pierre Boulez, who today would make just about everybody’s short-list of most important musicians and most irksome pills of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

On April 1, 1945 – roughly eight months after the liberation of Paris and a month before the end of the war in Europe – Messiaen, still working in relative obscurity – premiered a work for orchestra and chorus entitled Three Small Liturgies of the Divine Presence. Well, so much for relative obscurity; the piece unleashed a veritable storm of controversy. According to Messiaen’s biographer Robert Sherlaw Johnson:

“Overnight, Messiaen was condemned, on one hand, for his vulgarity and lack of good taste, and praised, on the other, for [having] a vivid imagination and true genius. The work was disliked by the avant-garde for what they regarded as his reactionary, [tonal] harmonies, and it shocked the conservatives because of [its] peculiar dissonances which, by this time, had become a feature of Messiaen’s style. The non-Christian was out of sympathy with the religious sentiments expressed, while the traditional Catholic was displeased by the apparently vulgar treatment of sacred ideas.”

Messiaen emerged from the merde stormsmelling like Chanel No. 5. You see, controversy attracts attention, and in those days immediately following the war the Western musical establishment was desperate to find new talent and new music that could represent the new reality of the post-War world.

And so, pretty much out of the bleu, the not-quite 37-year-old Olivier Messiaen received the commission – a dream commission – that would establish his international career.

Here’s what happened.

A short time after the premiere of Three Small Liturgies of the Divine Presence, Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra – the same Serge Koussevitzky who commissioned important early symphonies from Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, and William Schuman (among many, many others), who founded the Tanglewood Festival, created the Koussevitzky Foundation, and took on the young and brash Leonard Bernstein as his assistant and gave him the break that made his career – this Serge Koussevitzky contacted this “Olivier Messiaen” and made him an offer he could not possibly refuse. The offer: a carte blanche commission to write a symphony for the Boston Symphony Orchestra of any length, using any instrumentation he pleased, to be delivered whenever he finished it, no deadline.

Talk about a dream gig; I’m still waiting.

It was a spectacular opportunity, a commission to which Messiaen dedicated over two years of his life, from 1946 to 1948. Never having written a symphony, never having even considered writing a symphony, Messiaen wrote a symphony that was a summation of everything he loved and knew and believed in at that time: Eastern religions and a very personal sort of pan-theistic spirituality; Gregorian chant; birdsong; ancient Greek scales; and ancient Hindu rhythmic constructs. The result was a ten-movement, one-hour-and-twenty-minute symphony scored for large orchestra, piano (an extremely virtuosic piano part; there are portions of the piece that more closely resemble a piano concerto than a symphony), and an early electronic keyboard instrument called an ondes martenot (so-called because “ondes” means “wave” – as in “sound wave” – and “martenot” refers to Maurice Martenot, who invented the instrument in 1928).

Messiaen called his sprawling, one-of-a-kind new work the Turangalîla Symphony. The word “Turangalîla” is derived from two Sanskrit words: turanga and lîla. “Turanga” means “time”, and, by extension, “movement” and “rhythm”, activities marked by physical movement that take place in time. “Lîla” means literally “play”, “sport”, or “amusement”. According to Robert Sherlaw Johnson:

“[‘Lîla means] ‘play’ in the sense of divine action of the cosmos; that is, the acts of creation, destruction, reconstruction, and the play of life and death. It can also mean ‘love’. [‘Turangalîla], therefore, means ‘a song of love’, ‘a hymn to joy’, time, movement, rhythm, life and death.”

The Turangalîla Symphony was premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Boston, on December 2, 1949, under the baton of Serge Koussevitzky’s 31-year-old, Massachusetts-born protégé, Leonard Bernstein. In his program note for the premiere, Messiaen wrote:

“The TurangalîlaSymphony is a hymn to joy, a joy that is superhuman, overflowing, blinding, unlimited. Love is present here in the same manner: this is a love that is fatal, irresistible, transcending everything, suppressing everything outside of itself, a love such as is symbolized by Tristan and Isolde.”

For lots more on Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphony I would direct your attention my Great Courses/Teaching Company survey “The Symphony”, which can be examined and downloaded at RobertGreenbergMusic.com – where through December 27, everything is on sale!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More