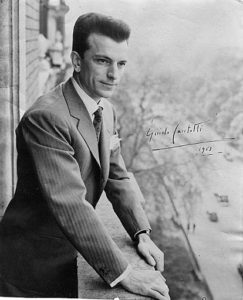

We mark the birth – on April 27, 1920, 100 years ago today – of the conductor Guido Cantelli, in Novara, Italy, some 30 miles west of Milan.

Perhaps the most overused words in our top-ten culture of superlatives are “genius” and “hero”. We’ll contemplate the word “genius” (and the folly of its current usage) at another time. For now, I’d ask that we consider the word “hero”.

Heaven knows, given the state of our world just now, we need heroes more than ever: people we can look up to and be inspired by; people whose accomplishments and decency remind us all of how good we can be. But I also think that, perhaps, we require heroes too much and as a result we elevate many individuals of questionable heroic worth to that lofty status just, well, because we can.

The word itself derives from the Greek ἥρως (hērōs), which means, literally “protector” or “defender”. Both “protector” and “defender” imply someone who would stand in harm’s way for some greater good. And that is indeed the operable definition of a hero or heroine: “someone who, in the face of danger, combats adversity; who performs great deeds or selfless acts for the common good.”

What actually constitutes a “great deed” will vary from person to person.

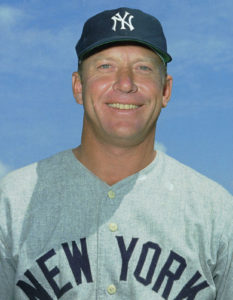

Growing up when and where I did, the center fielder for the New York Yankees, number “7”, Mickey Charles Mantle (1931-1995) was considered a certified, Grade “A” hero. Granted, the Mick was a great baseball player, but a hero by my definition? Not on your life. He was a drunk and personally something of a pig who ran around the base paths and caught, threw, and batted a 5¼ ounce, cow hide covered ball. I love baseball as much as the next guy; no, actually more, but playing – even excelling – in the game of baseball is not, in itself, a “great deed.”

At least not in my opinion.

I live in the Montclair neighborhood of Oakland, California, the population of which is some 430,000 people. Aside from downtown, Oakland consists of a number of discreet neighborhoods, most with their own commercial area, or “village”. Our area, called Montclair Village, is a quaint and most attractive district of services, restaurants, banks, realty offices, workout facilities, etc., anchored at the south end by a Safeway at the north end by a Lucky supermarket.

I’ve been shopping at the Lucky since 1986. If a store can be a great neighbor, then this one is indeed a great neighbor: during our numerous power blackouts last fall (due to the potential for wildfires here in Northern California), a semi-trailer sized generator was brought in to keep the store open and the ice flowing. And during the pandemic, the store and its magnificent employees has not missed a beat; it is open from 5am – 6am for first responders/doctors; 6am-7am for seniors; and remains open for everyone else until 10pm.

As I work at home, I used to shop almost daily pre-pandemic. As such, I got to know the names of almost every check-out person and bagger in the store and something of their lives. These wonderful people (most of whom are women) haven’t missed a beat. They are there every day, checking and bagging. Now I know that Woody Allen once posited that “80% of success in life is just showing up”, and in this I cannot disagree, although I’d edit his number up to maybe 90%. We are all aware that the good people manning our markets are indeed “showing up”; that’s their job. But they are also willfully – and in the case of our Lucky market, cheerfully – putting themselves in harms way every day. Mickey Mantle? You’ve got to be kidding me. You want to talk heroic behavior? I’ll take Crystal, and Early, and Maria, and Damian, and Shirley, and Tien, and Beverly any day over The Commerce Comet.

Putting one’s self in harm’s way for the greater physical and/or moral good: hello, that’s true heroism. Let us add to our short list of people who must often act heroically members of the military, law enforcement, first responders, fire fighters, front line nurses, orderlies, and doctors, and heaven help them, middle school teachers, who without any doubt put themselves in harm’s way on a daily basis!

If I may be so bold as to suggest, artists and writers and musicians are – generally speaking – some of the least heroic people among us. And this is how it must be. For a painter to be able to paint, for an author to be able to write, for a composer to be able to compose, for a musician to be able to practice, all-the-above require a big-time comfort zone: a safe, quiet, solitary space in which to work; the necessary equipment and supplies with which to work; and an audience to consume their work. Being an artist, author, or musician absolutely requires a degree of selfishness that precludes these fine people, by the nature of their work, from putting themselves in harm’s way. (On these lines, I know pianists who won’t even shake hands; not because of Corona but because they fear damage to their precious fingers! Oh my.) As a composer, I am well aware that the greatest danger I face on a daily basis is tripping over the cat while walking downstairs, coffee mug in hand, to my studio.

However, every now and then, political reality forces artists and musicians to make moral choices that can have fateful consequences on not just their careers but on their lives and personal health as well. The rise of Italian Fascism and German Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s forced an entire generation of European artists and authors and musicians to make choices – moral choices and indeed, life choices – that took them far outside their comfort zones.

Principal among these individuals was the conductor Guido Cantelli.

Cantelli’s father Antonio Cantelli was a professional horn and trumpet player who conducted his own band in Novara, Italy. A gifted musician who was required to attend his father’s rehearsals and performances, young Guido quickly gained enough proficiency as a trumpet player to join his father’s band when he was still but “a small boy.” By the age of ten he was playing organ at a local church and he made his debut as a pianist at the age of 14. But like father, like son: from the youngest age Guido imitated his father by “waving his arms about”, and by the age of 10 he was, on occasion, conducting his father’s band.

In 1939 Cantelli matriculated at the Milan Conservatory where among his teachers was Antonio Votto (1896-1985), an assistant conductor at La Scala who had worked under the great Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957). Cantelli learned his craft conducting the student orchestra, and by the time he graduated in 1943, great things were expected of him. But those great things had to wait, because just weeks after his graduation, he was drafted into the Italian Army.

Parallel to the events of Cantelli’s early life was the rise of Italian Fascism.

Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy on October 28, 1922. No less than any other major European power, Italy had suffered terribly during World War One (1914-1918), and like Russia and Germany, it was wracked by revolutionary conflict in the years after the war, pitting the communists, socialists, and anarchists on one side against the right wing establishment and the fascists on the other. Virulently racist and violent, Mussolini “dismantled virtually all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power” and by 1925 had created a police state, with himself as Il Duce: “the leader”.

The would-be revolutionary Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) looked at what Mussolini was “achieving” in Italy and literally swooned with desire. Hitler came to power in January of 1933, and following Mussolini’s own playbook, destroyed German democracy and, within 18 months, had created a police state with himself as Der Führer: “the leader.”

On October 25, 1936 Germany and Italy declared an alliance which came to be known as the Rome-Berlin Axis. Mussolini’s Italy embarked on a war of conquest in Africa, and by 1939 had occupied Libya and Ethiopia. Hitler’s Germany began its war of conquest – and with it, World War Two – when it invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Italy bravely joined the war on Germany’s side on June 10, 1940, just as France was about to fall and Britain seemed poised on the edge of defeat as well.

As it turned out, Hitler would have been better off without Mussolini as an ally. The Italian Army, which had had a tough time fighting the Libyans and Ethiopians, was no match for the modern European, North American, or ANZAC (Australian/New Zealand) armies. Having obliterated the Italians in North Africa in 1942 and 1943, the allies invaded Sicily in July 1943, bringing the war to the Italian home front. Allied bombings of the Italian peninsula brought the Italian infrastructure to a standstill; raw materials and food were in desperately short supply; and on July 19, 1943, Rome was bombed from the air for the first time in its history.

For Italy, by July 1943, the war was lost. Mussolini was arrested on July 25, 1943 and the Italian people rejoiced, believing that their war was over.

Not so fast, il miei amici (my friends).

Italy signed an Armistice (cease fire) with the allies on September 3, 1943. Hitler’s Germany, all too aware that the allies now had a pathway straight up the Italian peninsula to Austria, immediately invaded Italy. On October 13, 1943, Italy declared war on Germany, and the chaos was complete as some Italian units now fought against the Germans while others continued to fight with the Germans.

Back, finally, to Guido Cantelli.

Cantelli hated the Italian Fascists almost as much as he hated the Nazis. No doubt, it was most unwise to express such sentiments during the early 1940s, but he was a lefty music student and I will tell you from experience that no one takes lefty music students very seriously. (I mean, what are they going to do? Play their oboes out of tune? Break the strings of their pianos?) But then, in the late spring of 1943, Cantelli was drafted into the Italian Army at just the moment everything was falling apart in Italy. The 23-year-old draftee point-blank refused to swear an oath to Italian Fascism, and when pressed by the authorities he:

“was very outspoken about Hitler and the Nazis.”

So outspoken that he was bundled off to a Nazi slave labor camp in the Pomeranian German city of Stettin (today Szczecin, in Western Poland), where he was worked and nearly starved to death. In early 1944, near death from exhaustion, disease, and starvation, Cantelli was transferred to a prison hospital in the northern Italian city of Bolzano, where a sympathetic chaplain helped him to escape back to his hometown of Novara. Cantelli tried to hide in plain sight – he took a job as a bank clerk – but to no avail. He was identified and arrested by the fascist authorities and sentenced to death by firing squad. But in a classic case of “saved by the bell”, the prison in which Cantelli was being held was liberated in late 1944 before the sentence could be carried out.

The upshot: the 23 and 24-year-old Guido Cantelli was prepared to sacrifice his life for the moral outrage he felt towards the fascist and Nazi regimes. Speaking personally, I have never been so tested; really, very few (if any) of us have.

I stand in awe of his moral strength and conviction. This is my definition of a hero.

And now, “the rest of the story”, which in its own way is almost as painful as the story that has just preceded it.

Cantelli never entirely recovered his health after his incarceration, and debilitating illness plagued him for the remainder of his short life. Nevertheless, he got on with his career as a conductor, quickly becoming one of the most respected conductors in all of Italy. In May of 1948, the 81-year-old Arturo Toscanini attended a series of rehearsals Cantelli led at La Scala and was, very simply, blown away. He arranged for Cantelli to conduct his own NBC Symphony in New York City, and was further blown away. Toscanini gave Cantelli a letter to take home to his (Cantelli’s) wife Iris, in which he (Toscanini) wrote:

“I must personally tell you that it is the first time, during my long artistic career, that I find a young man truly endowed with those qualities that can’t be debated but that are the real ones, those that carry an artist high up – very high up.”

Cantelli was indeed one of the most prodigiously gifted conductors of his generation. Like his father the bandmaster before him, he was a perfectionist. He conducted all of his rehearsals and performances from memory and was said to be able to “draw the most virtuosic playing from his musicians.”

Thanks to Toscanini’s support, he was vaulted into the upper echelon of the musical establishment. The cliché be damned, Cantelli became like a son to Toscanini; he was almost universally acknowledged to be not just Toscanini’s protégé, but his “successor”.

On November 16, 1956, Cantelli was named the new Music Director of La Scala and was, at the same time, the front-runner to succeed Dmitri Mitropoulos as the Music Director of the New York Philharmonic.

On Saturday morning, November 24, 1956, eight days after his appointment at La Scala, Cantelli was in his seat on Linee Aeree Italiane (L.A.I.) flight 451. The flight, which had originated in Rome, was taking off from Paris’ Orly Airport on route to New York, where Cantelli was scheduled to conduct the New York Philharmonic. The big Douglas DC-6B, piloted by Captain Attilio Vazoller, an experienced trans-Atlantic pilot, carried a full load of fuel and had hardly gotten off the ground when something terrible happened. The plane lost altitude, clipped a two-story building, and fell into the village of Paray Vielle Post just south of Paris. 33 of the 35 people aboard the plane were killed, as was a child on the ground. Guido Cantelli was not among the survivors.

The crash was a tragedy for everyone involved, and a particular tragedy for the world of music, which saw, literally, one of its most promising talents go up in flames; having survived the Nazis and the fascists, Guido Cantelli could not survive a burning DC-6. The conductor Francesco Siciliani took Cantelli’s place as Director of La Scala, a position he held from 1957 to 1966. In Cantelli’s likely place, Leonard Bernstein was appointed to succeed Dmitri Mitropoulos at the New York Philharmonic, effective 1958. Had he lived, Guido Cantelli would have almost certainly become a household name on par with those of Toscanini and Bernstein.

At the time of Cantelli’s death, Arturo Toscanini was 89 years old and in fading health. Toscanini – awaiting Cantelli’s arrival in New York – was not told of his death; his family believed the news would kill him. Instead, they arranged for a fake telegram to be sent from Milan, purportedly written by Cantelli:

“Owing to unforeseen terrible attack lumbago forced to delay departure and put off joyful re-embrace [of] you. With all my affection, Guido.”

Toscanini died on January 16, 1957, 54 days after Cantelli, never having learned of Cantelli’s death. That, at least, was a small mercy.

We toast the 100th birth of a great musician and a genuine hero: to Guido Cantelli. Salud, caro maestro!

Join me on Patreon, where tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post will celebrate the Afro-Cuban jazz of the remarkable percussionist John Santos and the band Machete.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More