We note the death on June 8, 1839 – 181 years ago today – of the German soprano Aloysia Weber Lange. Don’t know who she is? You will soon enough.

Our story begins in March of 1777, in the city of Salzburg, in the spacious 8-room apartment at No. 8 Markartplatz that the Mozart family called home. It was there and then that it was decided that Salzburg was no place for someone as talented as the 21 year-old Wolfgang, and that a job commensurate with his great talents could only be found in that greatest of cities: Paris.

On March 14, 1777, Mozart’s father Leopold petitioned the Prince of Salzburg – Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo (1732-1812) – for permission to take Wolfgang “on tour” to Paris. Such leaves-of-absence had never been a problem in the past, as young Mozart’s European tours had brought tremendous prestige to his hometown of Salzburg. But it was a problem now; the archbishop had had enough of his Kapellmeister (Leopold) gallivanting around Europe with his snotty little son. The archbishop turned down the petition and threatened Leopold with dismissal. Wolfgang, likewise threatened, quit his job as concertmaster of the court orchestra before he could be fired. Leopold, terrified by the thought of his 21 year-old son traveling across Europe alone, sent his wife in his stead: Mozart’s mother, Anna Maria.

(Poor Leopold Mozart. This entire episode with the archbishop left him apoplectic with rage. For the first time in 15 years, if he wanted to earn a living at Salzburg, he actually had to do those things he had been hired to do, like give keyboard lessons to the choirboys, purchase music and musical instruments for the court, and, on occasion, direct the court’s music. There’d be no visit to Paris; Leopold had to stay home and work. It was . . . inconceivable!)

In September of 1777, four months shy of his 22nd birthday, Mozart and his mother left Salzburg for Paris. They reached the city of Mannheim – 370 miles west of Vienna – on October 26. Cold weather was setting in, and as Mannheim had a rich and active musical community, Wolfgang and Anna Maria decided to spend the winter there, and there they remained until March 1778.

In fact, soon after arriving, a particularly juicy position almost fell into Mozart’s lap: that of court composer at Mannheim. In the end, Mozart did not get the job: he was considered too young, too inexperienced in directing other musicians, a little too proud of himself and not nearly obsequious enough. Disappointed though he was, Mozart was easily able to make a living as a free-lance composer and music teacher before the planned move to Paris in the spring.

Mozart’s mother proudly wrote home to Leopold during this period of freelancing:

“He has so much to do, that he really doesn’t know whether he is standing on his head or on his heels. What with composing and giving lessons he hasn’t had time to visit anybody.”

Among Mozart’s students in Mannheim was a gifted 16 or 17 year-old soprano being groomed for a solo career on the opera stage, a beautiful young woman by the name of Aloysia Weber.

Ah.

She was born in the town of Zell im Wiesental in the very southwestern corner of Germany around the year 1760, the second of four sisters. The family moved to Mannheim soon after her birth. The Webers were a musical family: Aloysia’s father, Fridolin, was a professional violinist; her elder sister Josepha (1758–1819), was a soprano who would go on to premiere the role of the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute; Aloysia’s younger sister Constanze (1762-1842) was a trained soprano who would go on to marry Wolfgang Mozart on August 4, 1782; and her youngest sister Sophie (1763-1846), also a trained singer, sang at the Burgtheater in Vienna in the 1780s and was with Mozart when he died on December 5, 1791.

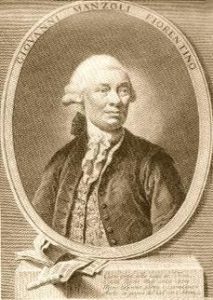

All the Mozartian connections to these Weber girls were still in the future when Aloysia met Wolfgang in the fall of 1777, when she began taking singing lessons from him. (Singing lessons from Mozart? Yes indeed: as a child, Mozart had trained as a singer with the well-known castrato Giovanni Manzuoli [1720-1782] in 1764 and 1765, while he – Mozart – was living in London. Mozart publically performed as a singer until his voice broke in 1769, when he was 13. And, of course, by the age of 21 Mozart was a veteran of the opera house as a composer and conductor.)

Aloysia Weber was an already advanced singer when Mozart began to work with her, though he felt that he could help her develop her coloratura, that is, her virtuosity in fast passages and embellishments. In a letter to his father he wrote:

“[MademoiselleWeber] sings from her heart and most likes singing cantabile [meaning in a smooth, song-like style]. I have brought her through the grand aria to the passages, because it is necessary when she comes to Italy for her to sing bravura arias [meaning highly virtuosic arias]. She will certainly not forget cantabile, because that is her natural inclination.”

Aloysia proved to be an excellent student, and to celebrate the completion of her lessons with Mozart in February 1778, he composed for her the recitative and aria titled Alcandro, lo confesso/Non sò, d’onde viene (“Alcandro, I Confess It/I Do Not Know from Whence it Comes”), K. 294. Regarding this recitative and aria Mozart wrote to his father:

“When I had it ready, I said to Mademoiselle Weber: learn the aria yourself, sing it as you wish; then let me hear it and I will tell you honestly what I like and what I don’t like. After two days, I came and she sang it to me, accompanying herself. Then I was obliged to admit that she had sung it exactly as I had wanted it and as I would have taught it to her myself. That is now the best aria she has; with it she certainly brings credit on herself wherever she goes.”

There can be no doubt that Aloysia Weber was a first rate prima donna. Writing many years later (in 1826), the famed Irish tenor Michael Kelly (who played the roles of both Don Curzio and Don Basilio in the premiere of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro) remembered Aloysia Weber this way:

“She had a greater extent of high notes than any other singer I ever heard. Her execution was most brilliant.”

(In this, Kelly wasn’t whistling “The Barber of Seville”. Another recitative and aria Mozart composed for Aloysia, Lo non chiedo, eterni Dei (K. 316/300b) contains two G6s: that’s the G two octaves and fifth above middle C. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, this is the highest pitch ever written for the human voice, but in this, the ordinarily unimpeachable Guinness Book is wrong. The highest pitch ever written for the human voice is the A6 almost three octaves above middle C that appears in the opera Das Irrlicht – “The Wisp” – by Ignaz Umlauf [1746-1796], a pitch – not incidentally – also written for Aloysia Weber!)

Wolfgang Mozart was neither the first nor the last man to fall head-over-heels in love with a beautiful, talented soprano, and that’s precisely what happened. There in Mannheim, Mozart experienced love and success: success free from his father. Bless him, the young dude, feeling his oats, made the executive decision to stay put, and wrote to his father, informing him that would be staying on in Mannheim, where Aloysia’s father Fridolin would help him to find work.

True to form, Leopold went ballistic; the twin prospects of being replaced by Herr Weber and of being deprived of Wolfgang’s future income as a result of marriage were unthinkable. He wrote back to his son:

“I have read your letter of the 4th with amazement and horror. For the whole long night I was unable to sleep and am so exhausted that I can only write quite slowly.”

During the course of this letter Leopold laid a guilt trip on Wolfgang worthy of a psychiatric professional, concluding the letter with the command:

“Off with you to Paris! And that, soon! Find your place among great people.”

For not the last time in his life, a heartbroken Wolfgang Mozart did what his father told him to do. He and his mother packed up and left Mannheim and arrived in Paris on March 23, 1778.

We must make quick work of the painful events that followed.

Forced to part from the girl he loved, aware that his family’s hopes and future were riding on his shoulders, Mozart did what any normal, red-blooded 22 year-old would have done under such circumstances: and that is, he rebelled. He decided that he hated Paris and the Parisians, who in turn did their best to return the sentiment. Then, on July 3, after a three-week illness, Mozart’s mother Anna Maria died in their shabby, flea-bag Paris apartment. Wolfgang was with his mother when she died. He was traumatized, as any of us would have been. He later wrote that:

“As long as I live I shall never forget it. You know that I had never seen anyone die. How terrible that my first experience should be the death of my mother! I dreaded that moment most of all, and I prayed earnestly to God for strength.”

Leopold Mozart – molto grazie, Pop – chose not to spare his son further grief. Someone had to be blamed for his wife’s death, and Wolfgang, being closest at hand, was the obvious choice. Leopold turned his own guilt and his own responsibility over the death of his wife onto his son, behaving, frankly, like a pig.

He also wanted Wolfgang back home in Salzburg, under the umbrella of his own “protection.” Through equal parts sniveling and begging, Leopold managed to obtain for Wolfgang an appointment as court organist back in Salzburg. Then, in a series of letters almost too vicious to read, Leopold harangued, cajoled, accused, abused, and bullied his son in order to force him to return to Salzburg.

(Leopold wrote: “I hope that you, after your mother had to die so inappropriately in Paris, that you will not also have your father’s death on your conscience.”

Nice.)

So it was that Mozart – disheartened, disappointed, enraged, frustrated, confused, and still grieving for his mother – set out for Salzburg. But, alas, he had one last kick-to-the-groin to sustain before arriving home to dear old Dad. Mozart stopped at Mannheim, there to see his beloved Aloysia and to ask for her hand in marriage. While he’d been away in Paris, Aloysia’s singing career had advanced very nicely, without any of the help Wolfgang had promised her. Mozart’s first biographer, George Nissen, describes Wolfgang and Aloysia’s “reunion”:

“Mozart, upon his return from Paris, mourning for his mother, found that Aloysia’s sentiments for him had changed. When he entered, she appeared no longer to know him, for whom she previously had wept. Accordingly, he sat down at the piano and sang in a loud voice” Leck mir das Mensch im Arsch, das mich nicht Will: “The one who doesn’t want me can lick my arse.”

This small victory notwithstanding, it was a humbled and humiliated Mozart that returned to Salzburg to take the job as organist for the despised Archbishop Count Hieronymous Colloredo.

But not for long. Three years later – in May of 1781 – Mozart left Salzburg, the archbishop and his father for good and put out his shingle in Vienna. It was there that he was reunited with the Weber family, which had recently relocated to Vienna from Mannheim. He married Constanze Weber, and, letting bygones-be-bygones, forged a new relationship with his now sister-in-law Aloysia. He continued to compose for her, and among other roles, Aloysia played Donna Anna in the Viennese premiere of Don Giovanni on May 7, 1788.

On October 31, 1780, Aloysia married an actor and amateur painter named Joseph Lange (1751-1831). It was Lange who painted what is universally acknowledged as the single best likeness of Mozart, a portrait dating to 1782 or 1783.

In 1789, Lange affixed this portrait to a larger canvas, intending to depict Mozart playing a piano, but that larger version was never completed. The unfinished painting hangs, today, in Mozart’s birth house at No. 9 Getreidegasse in Salzburg.

Postscript

Long after Mozart’s death in 1791, Aloysia Weber Lange – who had so rudely rejected Mozart’s marriage proposal in 1778 – was asked how she could have spurned someone as brilliant as Wolfgang Mozart. Her reply:

“I did not know, you see. I only thought, he was such a little man.”

For scads more on Mozart, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses/Teaching Company surveys on Mozart’s life, operas, and chamber music.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More