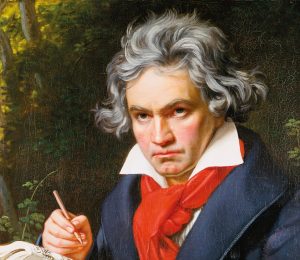

We mark the birth on December 16, 1770 – 249 years ago today – of Ludwig, or Louis, or Luigi (he went by all three names) van Beethoven, in the Rhineland city of Bonn. Although there is no documentary evidence confirming that Beethoven was actually born on the 16th, we assume – with that proverbial 99.99% degree of certainty – that he was. This is because the Catholic parishes of the time required that newborns be baptized within 24 hours of birth and Beethoven’s baptism was registered at the church of St. Remigius on December 17, 1770.

As we brace ourselves for the hoopla celebrating the 250th year of Beethoven’s birth, we pause and ask ourselves, honestly, why Beethoven: why do we, as a listening public, so adore his music?

I would answer that question by drawing on some material from my recently published “Audible Original Course”, Beethoven: The First Angry Man (which, gratuitously, will be the topic of tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post).

The evidence of our ongoing passion for Beethoven’s music is everywhere to be found.

“Classic FM” is one of the United Kingdom’s three independent National Radio Stations and one of the most listened-to “classical music” radio stations in the world. The station conducted a favorite composer poll in 2016 that attracted 170,000 votes; according to Classic FM, that response made the poll “the biggest public vote in the world on classical music tastes.” The winner of this not-particularly-scientific-but-nevertheless-not-uninteresting popularity contest was Ludwig van Beethoven.

Encyclopedia Britannica’s on-line site lists the “10 Classical Music Composer to Know” in the order in which we should presumably “know” them. Number one on that list? Beethoven. (Yes, of course I will name the remaining nine. In order they are: J.S. Bach, Wolfgang Mozart, Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy, Peter Tchaikovsky, Frédéric Chopin, Joseph Haydn and Antonio Vivaldi.)

“YouGov”, an internet site that specializes in polling, lists “The most popular classical composers in America.” At number one is Beethoven, followed by Mozart, Bach, Chopin, George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Leonard Bernstein and Handel.

“DigitalDreamDoor’s” list of “100 Greatest Classical Composers” begins with Beethoven.

The internet site “Ranker” puts Beethoven at the top of its list of “The Best Classical Composers,” as does the site “List 25” in its “25 of the Most Celebrated Composers in History” AND the site “The Top Tens” in its list of “Greatest Classical Composers.”

(Bucking the trend, the New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini named Johann Sebastian Bach – or just “Sebastian” Bach, as his friends and family knew him – as the number one composer on his “The Top Ten Greatest Composers” list, published in 2011. For our information, Beethoven himself would have agreed entirely with Tommasini’s estimation of Bach. Number two on Tommasini’s list? Beethoven.)

According to The League of American Orchestras, between 2006 and 2012 (the most recent data I could find), American orchestras performed the music of Beethoven more than that of any other composer: in that six-season span, there were 3305 performances of Beethoven’s orchestral music. (At number two was Mozart, with 2976 performances; no one else came close.)

I’d be happy to go on, but I expect it’s time to stop, as the point has been made: for reasons we will identify, Ludwig (“my friends call me ‘Louis’”) van Beethoven, the bad boy from Bonn – bad hair, bad attitude, bad karma – is a compelling, audience favorite nearly 200 years after his death.

Again, we ask why? It’s not because his music is particularly “pretty” or “entertaining”, which it is not. It’s not because it’s especially “easy” to listen to, which it most certainly is not.

It’s not because Beethoven was a “natural composer”, a technical wizard like Sebastian Bach or Wolfgang Mozart (for example), who neatly wrote down their music in full score with nary a sketch, cross-out or correction. Beethoven, on the other hand, often worked for months – and later in life, sometimes for years – on a single piece, tirelessly sketching, reworking, erasing, crossing-out, and rewriting until his manuscripts looked more like a Jackson Pollock painting than a piece of music, indecipherable to anyone but his copyists (and, on occasion, indecipherable to them as well!).

And it’s not because Beethoven was a “genius”, a word so overused in our top ten culture of superlatives as to have no more meaning than the phrase “real imitation margarine!” Yes, okay, whatever, Beethoven was a “genius”, but again, in terms of pure, incomprehensible genius, he was not on the level of Sebastian Bach and Wolfgang Mozart. Those guys – Bach and Mozart – wrote perfectly crafted music in virtually every extant musical genre that existed in their time at a speed and in a number that leaves us shaking our heads in disbelief! I like the way the English pianist James Rhodes puts it:

“Bach and Mozart had gifts that came straight from God. I’m an unbeliever, but there is simply no other possible explanation for the depth of genius they displayed. What Bach and Mozart did with music is quite literally beyond any human comprehension.”

For all his “genius”, Beethoven was – and remains – one of us. He fought with his muse; he wrestled and raged and dug to the depths of his soul to find the means to say – musically – what he had to say. At the core of Beethoven’s expressive message was his own life: his humanity. Unlike Bach and Mozart, each of whom created in his music a better, idealized world; a place of truth and beauty and rightness that exists beyond the futility of the everyday, music that to my ear virtually describes paradise, Beethoven’s expressive world dwells here on earth, among his fellow humans. Obviously, he was not the first man “to be angry”, but he was the first composer to allow his emotions to explicitly inform his music; the first composer to espouse the notion that music composition was and had to be a vehicle for profound self-expression. At a time when composers existed on bended-knee and worked for the church or the state or the aristocracy, Beethoven declared in word and deed that his music was for him and about him and you can take it or leave it!

As a composer, Beethoven was the first modern: the first composer to consciously and repeatedly put his own expressive needs before the stylistic and expressive norms of his time. It wasn’t that he went outside that clichéd “box” (as did both Bach and Mozart); no, when it came to the expressive content of his music, Beethoven actually obliterated “the box”; he stomped on it like some jack-booted Hell’s Angel in a barfight, and by doing so created an entirely new paradigm for Western music: that of a composer consciously and often explicitly mirroring his own life experience in his music.

Life was unkind to Herr Beethoven. He grew up to be a deeply scarred man: surly, rude, and suspicious; late in life, even paranoid; predisposed to obsessive-compulsive and even delusional behaviors; a physically clumsy, sometimes suicidal, socially graceless dude who really needed to work on his hair and his personal hygiene.

But – yes, there’s always a “but” – he was also a deeply passionate, deeply loving and at times lovable man, one who aspired to be honorable and noble and to serve humankind through his music.

All of these conflicting aspects of his personality found their way into his music; and consciously or unconsciously, we hear all of this in Beethoven’s music. It is music that stuns us with its power and passion; delights us with its lyricism; awes us with its magnificence, but most importantly inspires us in the manner in which it depicts Beethoven’s humanity.

So back to the admittedly ridiculous top-ten, top-25, top 100, top-o’-the-morning lists previously discussed.

Why should the almost universal declaration of Beethoven as being – today – the most “popular” composer in history mean anything given the entirely subjective nature of such popularity?

This is why. Beethoven’s music – with its anger and pain, passion and beauty; with its primal rhythmic power and its striving and battling in search of exaltation – is, for us, here, today, like looking in the mirror. In his music we hear our own lives; the dramatic narratives in his music resonate with our own experience; with our own anger and pain, with our own striving for something better in a world that can be both dreadfully brutal and, at the same time, very beautiful. His is a body of music that feels wholly modern in our own, troubled times.

The great Beethoven conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler wrote this in 1936:

“In Beethoven’s works Music and Soul are one. Even to attempt to separate the one from the other is an offence. Through [his] music shall we gain access to the soul of this great man; nay, more: it is only in full awareness of our humanity that we shall fully grasp the tremendous reality of his music.”

For lots more on Beethoven’s life, times, and music I would direct your attention to my courses The Symphonies of Beethoven, The String Quartets of Beethoven and The Piano Sonatas of Beethoven, and more, all published by The Great Courses/The Teaching Company and available for examination and download at RobertGreenbergMusic.com. I would also recommend following my Patreon channel for even more Beethoven during the Beethoven 250 year especially.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More