We mark the birth on July 8, 1900 – 119 years ago today – of the composer, pianist, author, inventor and self-described “bad boy of music”, George Antheil (pronounced Ann-tile).

Antheil lived a fascinating life. He composed a lot of music, including six operas, twenty works for orchestra (including six numbered symphonies); 15 major works of chamber music (including three string quartets and four violin sonatas); scores for over 30 movies and lots of music for TV. He wrote magazine and newspaper articles, and wrote three books, including a crime novel edited and published in 1930 by his friend T. S. Eliot entitled Death in the Dark. And he invented stuff.

For all of this, he is remembered – when he is remembered at all – for his firstmajor composition, a work entitled Ballet Mécanique and for having invented and patented, along with a woman known best by her stage name as Hedy Lamarr, a system for the radio control of airborne torpedoes that made them impervious to jamming. (Yes, I will tell that story!)

Antheil was born and grew up in Trenton New Jersey and died in New York City (a heart attack) on February 12, 1959.

He started piano lessons at six, and by the time he was in his late teens he had become a formidable (if idiosyncratic) pianist.

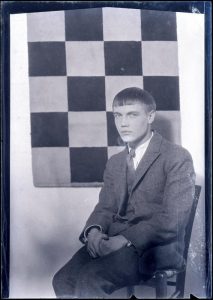

Margaret Caroline Anderson, the founder, editor and publisher of the extremely influential art and literary magazine The Little Review described the roughly 20-year-old Antheil as being short, as having a strangely shaped nose, and as someone who played on the piano:

“a compelling mechanical music [that used] the piano exclusively as an instrument of percussion, making it sound like a xylophone or a cembalo.”

Antheil was a technology nut, and the music he composed in the early 1920s was obsessed with the “machine” as a metaphor for modern life. But more than just a good pianist with a modernist bent, and despite the fact that he never formally graduated from high school or college, Antheil had a combination of chutzpah, charisma and enthusiasm that enabled him to ingratiate himself to a wide variety of older people who today would be called “influencers.” These people included the aforementioned Margaret Anderson; the photographer Alfred Stieglitz; the conductor Leopold Stokowski; and the publishing heiress Mary Louise Curtis Bok, who founded the Curtis Institute of Music in 1924 and who underwrote Antheil’s career for twenty years, giving him the financial freedom to “follow his muse.”

It was as a self-styled “musical prophet” that the not-quite 22-year-old George Antheil set sail for Europe on May 30, 1922, intent on making a name for himself as – in his own words – “a new ultra-modern pianist composer” and a “futurist terrible.” He started out in Berlin but moved to Paris on the advice of none-other-than Igor Stravinsky (who Antheil temporarily managed to charm but who dropped him like a hot pierogi when he found out that Antheil was telling people that “Stravinsky admired his work”).

Paris was a hotbed of intellectual and artistic experimentation in the 1920s. Antheil rented a one-bedroom apartment above the famous left-bank bookshop “Shakespeare and Company.” Its founder and owner, Sylvia Beach – who was the first to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses – described him as:

“a fellow with bangs, a squished nose and a big mouth with a grin in it. A regular American high school boy.”

To which we would add a brash “American boy” with the gift of gab and an armload of talent. Antheil was described by his Parisian friends as a combination of Igor Stravinsky and James Cagney. Those friends were an impressive bunch, and they included Erik Satie, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Virgil Thomson, and Ernest Hemingway.

Antheil’s first major work, composed in Paris in 1926, is also his most famous work: the Ballet Mécanique. The Ballet Mécanique was originally intended to accompany an experimental film likewise entitled Ballet Mécanique. The film – created in 1924 – is a Dadaist art film conceived, written, and co-directed by the artist Fernand Léger in partnership with the filmmaker Dudley Murphy with cinematographic input from Man Ray. Goodness; Paris in the 1920s was a namedropper’s heaven. For our information, Antheil’s composition and the Léger-Murphy-Ray film were not actually heard-and-seen together until 1935, in a “performance” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.)

Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique was originally scored for 16 synchronized player pianos (called “pianolos”, Antheil devised a system that synchronized the pianos), 2 standard pianos, 3 xylophones, 7 electric bells, 4 bass drums, a tam-tam (a large suspended cymbal), a siren, and three airplane engines and propeller assemblies mounted on stands.

As we have observed Antheil loved machines and what he called the:

“anti-expressive, anti-romantic, coldly mechanistic aesthetic of the early twenties.”

He described his Ballet Mécanique as:

“Scored for player pianos. All percussive. Like machines. All efficiency. No LOVE. Written without sympathy. Written cold as an army operates. Revolutionary.”

The link to the robotic version of the Ballet Mécanique above runs under twelve minutes. If you find that roughly 11½ minute version too unrelentingly intense, imagine how the audience at the premiere at Paris’ Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on June 19, 1926 felt about the original, twenty-seven-minute-long version of the piece! Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique is devoid of reflection or feeling; it is music that would seem to mirror the same brutal, mindless, industrial war that had just slaughtered an entire generation of European men.

The audience’s reaction at the premiere was mixed, and the technical problems began immediately, when the large fans that were being substituted for the airplane engines began blowing off the hats and toupees of various audience members. The American writer Bravig Imbs (yes, that is a real name), described the scene:

“People began to call each other names and to forget that there was any music going on at all. Ezra Pound took advantage to jump to his feet and yell, “You are all imbeciles!” One fat, bald gentleman lashed out his umbrella, opened it, and pretended to be struggling against the gale of wind from the electric fans. His gesture was immediately copied by many.”

After the concert, fistfights broke out in the street between Antheil’s supporters and his detractors. It was the most substantial musical riot since the Paris premiere – at exactly same theater – of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring on May 29, 1913: 13 years, one month, and six days before. Antheil was thrilled. He wrote:

“From this moment on I knew that, for a time at least, I would be the darling of Paris. Paris loves you for giving it a good fight.”

Antheil returned to the United States for good in 1933. In 1936 he settled in Los Angeles, where he became a sought-after composer for film. In 1940, he met a Vienna-born woman named Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler (1914-2000). Antheil knew her by her stage name of Hedy Lamarr. (Lamarr was born Jewish but converted to Christianity at the insistence of the first of her six husbands when she was 19-years-old. Nevertheless, she left Europe for good in 1938 after the Anschluss that saw Nazi Germany absorb and annex Austria. She managed to get her mother out of Austria as well; they both eventually became naturalized American citizens.)

Lamarr signed her first contract with MGM in 1938; by the time George Antheil met her in 1940 she was one of MGM’s hottest stars and one of the greatest beauties ever to grace the screen. It was said that when her face appeared on screen:

“everyone gasped. Lamarr’s beauty literally took one’s breath away.”

However, Lamarr was much more than just a pretty face (she once said that “any girl can be glamorous; all you have to do is stand still and look stupid”). She was – like Antheil – a self-taught inventor of genius. She tinkered constantly, and invented – among other things – an improved traffic light and a tablet that when dissolved in water would make a carbonated drink. Lamarr herself judged the latter to be a failure, claiming that it tasted like Alka-Seltzer.

Antheil recalled their first meeting:

“We began talking about the war, which, in the late summer of 1940, was looking most extremely black. Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state. She said that she knew a good deal about munitions and various secret weapons and that she was thinking seriously of quitting MGM and going to Washington, DC, to offer her services to the newly established National Inventors Council.”

After America entered the war in December 1941, Lamarr learned that radio-controlled torpedoes – which were then a brand-new technology – could be easily jammed and thus sent off course. She figured that if the radio frequency controlling the torpedoes could be changed rapidly, in a semi-random sequence known only to the transmitter and receiver, jamming would become impossible. She contacted her friend George Antheil, and together they invented a system for the radio control of airborne torpedoes that made them impervious to jamming, a technology they called “frequency-hopping.” Lamarr and Antheil received a US Patent (#2,292,387) for the technology on August 11, 1942, although it wasn’t until the 1960s that the technology was finally adopted by the U.S. Navy. The principles of frequency-hopping are today a key element in Wi-Fi, CDMA, and Bluetooth technology. Under the heading of better-late-than-never, in 2014 both George Antheil and Hedy Lamarr were posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

A happy 119th, George Antheil!

For lots more on the music of the twentieth century, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, The Great Music of the Twentieth Century, which can be examined and purchased for download at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More