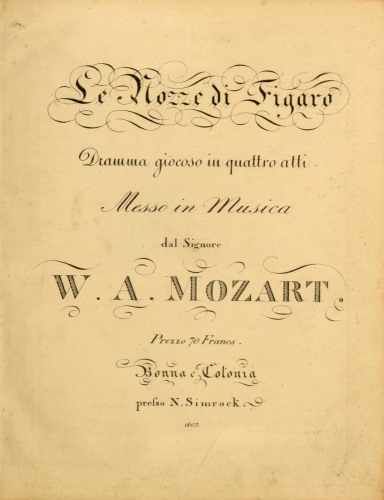

On May 1, 1786 – on what was also a Monday, 237 years ago today – a miracle was heard for the first time: Wolfgang Mozart’s opera The Marriage of Figaro received its premiere at the Burgtheater in Vienna.

Some 100 years later, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) wrote this about The Marriage of Figaro:

“Every number in Figaro is for me a marvel; I simply cannot fathom how anyone could create anything so perfect. Such a thing has never been done, not even by Beethoven.”

Herr Brahms, when you’re right, you’re right, and this case you are so right! 237 years after the premiere, Brahms’ awe of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro mirrors our own. For many of us – myself included – it is, simply, the greatest opera ever composed.

Composing an Italian Language Opera for the Viennese

On May 7th, 1783 – some three years before the premiere of The Marriage of Figaro – Mozart wrote the following in a letter to his father back in Salzburg:

“The Italian opera buffa [here in Vienna] is very popular. I have looked through more than a hundred libretti [meaning literally “little book,” the script of an opera] but I have found hardly a single one that satisfies me. That is to say, there are so many changes that would have to be made that any poet, even if he were to undertake to make them, would find it easier to write an entirely new text. Our poet here now is a certain Da Ponte. He has an enormous amount to do, and he is at present writing a libretto for Salieri, which will take him two months. He has then promised to write a libretto for me. But who knows if he will be able to keep his word, or whether he will want to? As you know, these Italians are very civil to one’s face . . . I should dearly love to show what I can do in an Italian opera.”

That Mozart would “dearly love” to compose an Italian language opera for the Viennese was an understatement; “desperately want” would have been a far more appropriate way to put it!

When the 27-year-old Mozart wrote that letter to his father in May, 1783, he had been living and working as a freelance musician in Vienna for almost exactly two years. The young dude was, at the time, filled with inestimable energy, ambition, and – of course – fathomless talent. Italian language opera was the most prestigious (and potentially profitable) entertainment medium of the day, and Mozart desperately wanted a piece of that action. But he was also savvy enough to know that composing an Italian language opera in the 1780s for the Viennese was an entirely different ball-of-notes than composing one for audiences in Salzburg, Munich, and even Milan, which he had done already. He was no longer a child prodigy, for whom the composition of any opera would stun audiences merely by dint of its exitance. By the 1780s he was a seasoned pro, composing for a Viennese audience that was, at the time, arguably the most discriminating one in Europe.

Consequently, Mozart knew that when the time came for him to throw his compositional hat into the Viennese ring (pun intended) by composing an Italian language opera for the toughest crowd this side of the Roman Colosseum, it couldn’t be just any opera. It would have to represent his best work, and as such it would have to be based on a really good story with a libretto by a first-rate poet. Which is why – during the course of his letter to his father – Mozart mentioned Lorenzo Da Ponte, the official “poet” (meaning the official “librettist”) of the Viennese Court.…

Continue Reading, and listen without interruption, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!Listen and Subscribe to the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More