I am aware – nay, more than aware – that this present post is an example of unconscionable conceit and vanity. Of this I stand justly accused; my head droops in shame and my present auto-flagellation will continue for minutes – perhaps for even the half-an-hour – to come.

What, you rightly ask, could have prompted this pre-emptive outburst of self-loathing? (“Pre-emptive” in that having abused myself, it is my hope that you will feel no need to do so as well.) What has brought this on? Just this: I am dedicating this week’s “Music History Monday” to an event that at the time of this writing has not yet occurred and once having taken place – on Monday evening, April 8, 2019 – will almost certainly not qualify as “music history.”That event? The world premiere of my piano trio, The Daughters of Atlas this evening in Berkeley, California.

Talking about your own music is like talking about your children or, worse, your grandchildren: it is almost impossible to do so without becoming a soporific bore, inducing drooling paralysis in those within earshot. Nevertheless, I am asked constantly how I go about writing a piece of music. Since I know how fascinated I am by the stories of how other composers do their thing, I’ve decided – casting my ordinarily Marianas Trench-deep humility aside – to share with you the process that created The Daughters of Atlas (or “DOA” as I’ve been referring to the piece in private).

At this point

(Joe Irrera is currently having back problems, so he has been sidelined and replaced for now by Miles Graber, a Juilliard-trained pianist and family practice doc who has been a mainstay on the Bay Area music scene for decades.)

I have heard violinist Hrabba Atladottir perform many times since she settled in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2008. She plays with fire (not with matches), passion and intense lyricism, which I showcased in particular in the central movement of DOA, a movement entitled “Siren’s Web: Calypso’s Song and Dance”.

I’ve known cellist Nina Flyer for over 25 years. She has played scads of my music and she is a ROCK; yes: think a tall, elegant woman with the musical muscles of Duane “the Rock” Johnson and you’ve got Nina. Her cello makes a big, sweet sound and she is equally adept at providing rock steady support in the bass and playing singing, lyric solo lines in any register. There’s hardly a measure in DOA where I wasn’t thinking “Nina Flyer” when I put pencil to the cello part.

Pianist Joseph Irrera is a formidable virtuoso, a fellow Steinway artist, so as I have an unfortunate tendency to do, I wrote a piano part the likes of which I wish I was able to play myself.

These, then, are the players for whom I knew I was going to compose. For me, the next step – long before I put a note on paper – was to come up with a concept for the piece, meaning a title. This has been my MO for as long as I can remember, and for me it works: if I know what the title of a piece is going to be, I know, up front – approximately – what the piece is going to be “about” and what it’s going to sound like. Since I was to be among the first composers to write for Trio Foss, I wanted the title – and the piece – to be Trio Foss specific.

“Foss” means “waterfall” in Icelandic, and an Iceland-connection runs strong through the group. The violinist, Hrabba Atladottir, is a native of Iceland, and the cellist Nina Flyer was, once upon a time, the principal cellist of the Iceland Symphony and a cello teacher at the Reykjavik College of Music (a.k.a. the Icelandic Conservatory of Music, the leading collegiate conservatory of music in Iceland).

For my title, I glommed onto the surname of Trio Foss’s violinist, Hrabba Atladottir. “Atladottir” means “daughter of Atlas”, and just like

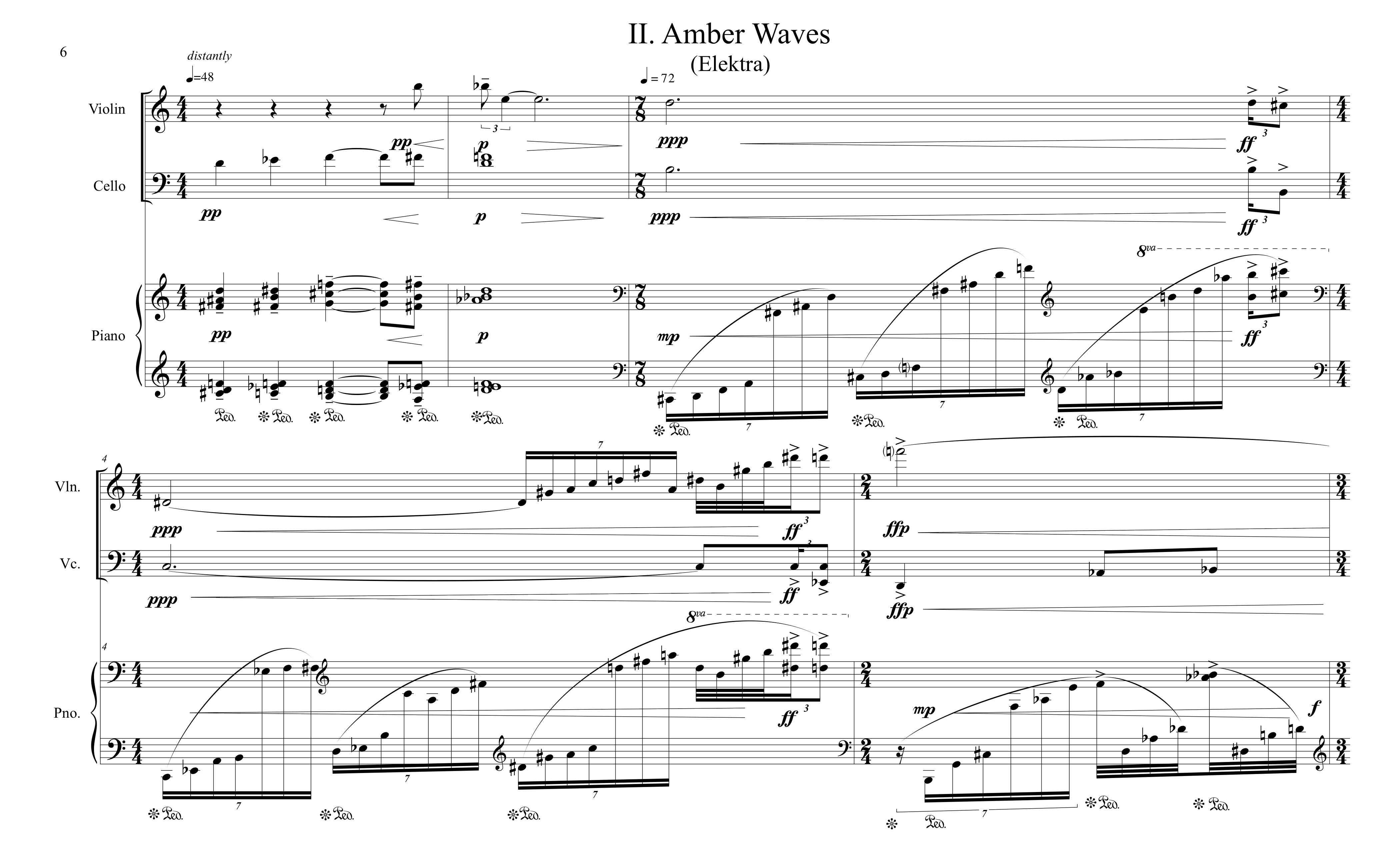

In ancient mythology, Atlas was the Titan god fated to hold up the sky and carry the weight of the world for eternity. Somehow, under those straightened circumstances, dude managed to father some pretty interesting daughters. One of those daughters is Elektra (no relation, by the way, to the mommy-killing whack-job “Elektra” of Richard Strauss’ opera). Elektra – which means “amber” – is one of the Seven Sisters, or Pleiades. The Seven Sisters are also known as the “Water Maidens” due to their association with water in all its forms, from rivers and oceans to rain, ice and snow. According to legend, Elektra’s son Dardanus (fathered by Zeus, no less) helped to found the city of Troy. When Troy was destroyed Elektra’s grief was such that she turned into a comet and vanished. I decided that Elektra’s movement would thus progress from “wind” and “water” to “waves”, “war” and finally, to “wander off into oblivion”.

Another of Atlas’ daughters is Calypso, who according to Homer managed to seduce and ensnare the itinerant Greek hero Odysseus, keeping him on her island for seven years by addling him with her singing, dancing, and sexual . . . virtuosity. Calypso – which means “to deceive”– is famous for weaving with a golden shuttle, weaving what I imagined to be a web of deceit that held Odysseus in its thrall.

The Pleiades are a group of seven daughters of Atlas known as the “seven sisters”. Given any environment dominated by seven sisters, there should be a lot of talking at the same time, yelling and arguing, in both good humor and bad. And most everything should happen in groups of seven.

I decided to bookend these three programmatic movements – Elektra, Calypso, and the Pleiades – with a movement entitled “Foss”, one that depicts the mummering, icy, vaporous image of a presumably “Icelandic” waterfall.

Having decided all of this before jotting down a note, it was finally time to sit down and actually write some music.

Job one was to come up with melodic profiles based on the names “Atladottir”, “Elektra”, and “Calypso”. (“Pleiades” is melodically invoked by rising 7-note diatonic scales).

Job two was to come up with a harmonic underpinning/progression that could support all of the melodic profiles. That harmonic underpinning – to be used throughout the piece in all sorts of permutations – was to become the principal unifying factor among the otherwise contrasting movements. (Yes, I know: this is trade talk and it is boring. Stay with me.)

From there, it was time to actually put things together and write.

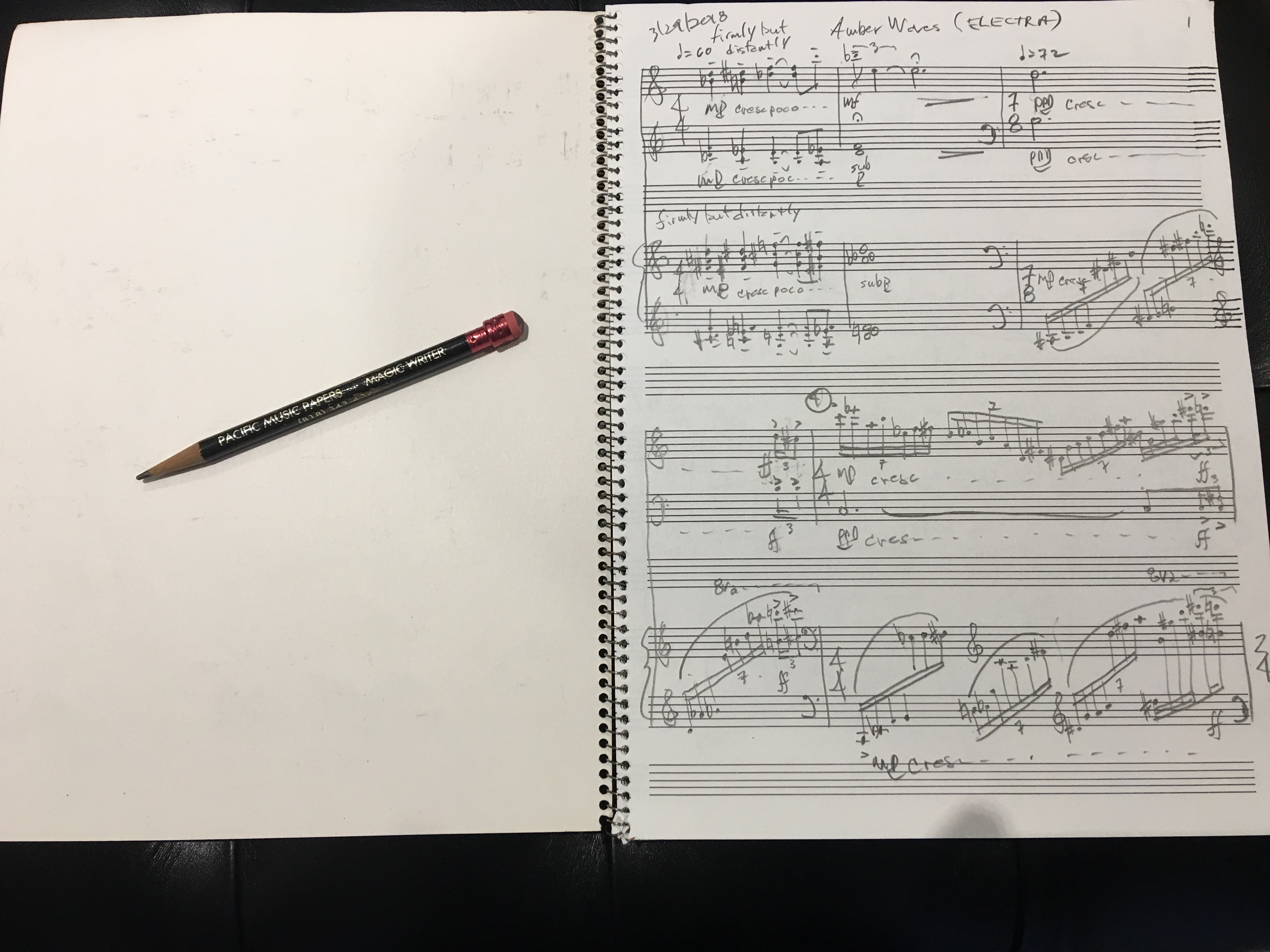

I confess that I compose at the piano; I will gladly admit to “hearing” best through my fingers. My working methodology is entirely analog: pencils (Pacific Music Paper No. 1 “Magic Writer” pencils) on paper (Passantino no. 85 12-stave, 96-page spiral bound music notebooks).

Once DOA had been so written by hand (and rewritten and rewritten and rewritten again), I created the finished score and parts using a software notation program called Finale.

(Many composers working today prefer to use a like program called Sibelius. One day I’ll write a post about all the music notation programs I have used – or more accurately, attempted to use – since roughly 1987, beginning with a program called Professional Composer created by a company called “Mark of the Unicorn.” That post will read like a disaster novel: a tragic, painful story recounting one failure after another; one epic waste of time and money after another; one howl of despair after another as 20, 40, even 60 hours of work disappeared into the ether thanks to some bug or another, never to be seen again. The pain is still fresh; my outrage still strong. On second thought, I might not, in fact, have the heart or strength to write that post.)

The beauty of Finale (or Sibelius, for that matter) is that the program can play back your notated score with a spectacular degree of accuracy. Too accurately, to be honest: the user must always remember that living human beings cannot play music as quickly or as accurately as a computer program. These programs are merely tools and not end-alls to themselves. Having said that, playing back a finished score on Finale allows me to make sure my phrases and overall pacing are right, and to correct such if they are not. (In the “old”, pre-digital days, one didn’t discover this until a second rehearsal or so, necessitating panicked rewriting on the part of the composer and creating unhappiness among performers, who generally do NOT like having to relearn a “corrected” score. Helpful hint: try, never, to make your players unhappy. A truism: happy players perform well and will make an audience happy. The math is simple: a happy audience = a happy composer; this is good. Unhappy players do not generally perform well and will likely not make an audience happy. An unhappy audience = an unhappy composer; this is not good.)

Once the piece was input, reconsidered yet again and the parts extracted, I delivered the score and parts to Trio Foss. Like a baby born, the piece was – from that moment – out of my hands, no longer my exclusive property but part of the world. Yes, DOA might in fact turn out to be a total delinquent, but once it was in Trio Foss’s hands, my work was done.

At our first rehearsal on Wednesday, April 3, I made my usual apologies for writing such a hard piece, feeling – as usual – more like the perpetrator of a crime than the creator of a score. And hard to play it is. But I’ve written it for pros, and so with fingers crossed I assume that all will go well tonight at Berkeley, California’s Freight & Salvage Theater.

For all-too-much more on my own music, I would direct your attention to the 24th and final lecture of my Great Courses survey, The Great Music of the 20th Century.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More