On December 10, 1896 (or November 28 in the old-style Russian Julian calendar) – 122 years ago today – Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s rewritten and re-orchestrated version of Modest Mussorgsky’s greatest masterwork, the opera Boris Godunov, received its premiere in St. Petersburg Russia at the Great Hall of the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s version of Boris – which presumably corrected all sorts of technical errors and flaws real or imagined in Mussorgsky’s original – held the stage until the last decades of the twentieth century, at which point Mussorgsky’s original version was finally embraced for the masterwork that it always was.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s reworking of Boris Godunov was both an act of love made with the best of intentions and a terrific disservice to a masterwork.

Let’s talk!

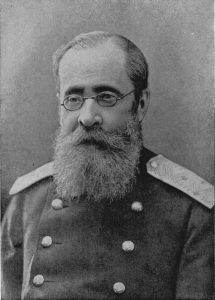

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (1839-1881)

Mussorgsky was born into a wealthy, land-owning family in the Russian district of Karevo, roughly 250 miles south of St. Petersburg. He began piano lessons at six, and his progress was such that at the age of 9 he performed a piano concerto by the then-fashionable composer John Field. When Modest was 10, his family relocated to St. Petersburg so that Modest and his brother Filaret could enter the military as per the Mussorgsky family tradition.

At 13 Modest entered the “Cadet School of the Guards” and upon graduating at 17, he received a commission with the elite Preobrazhensky Lifeguard Regiment.

All the while, Mussorgsky kept up with his music, and became something of a fixture in the toniest of St. Petersburg’s salons. It was at such a salon that the 17 year-old Mussorgsky met the 22 year-old Alexander Borodin. Borodin later described the small and immaculate Mussorgsky this way:

“His little uniform was spic and span, close-fitting, his feet turned outwards, his hair smoothed down and greased, his nails perfectly cut, his hands well groomed like a lord’s. His manners were elegant, aristocratic: his speech likewise, delivered through somewhat clenched teeth, interspersed with French phrases; rather precious. There was a touch—though very moderate—of foppishness. His politeness and good manners were exceptional. The ladies made a fuss over him. He sat at the piano and, throwing up his hands coquettishly, played with extreme sweetness and grace extracts from Trovatore, Traviata and so on, while around him buzzed in chorus: ‘Charmant, délicieux!’ and suchlike.”

Within two years of that evening with Borodin, Mussorgsky had fallen under the spell of the arch musical nationalist Mily Balakirev, eventually becoming a member of what was known as “Balakirev’s Circle”: a group of five composers (Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Cesar Cui, and Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov) that was dubbed the Moguchaya Kuchka, meaning the “Mighty Handful” or simply “The Five.”

In 1858, at the age of nineteen, Mussorgsky resigned his commission and took a civil service job with the post office in order to devote himself completely to his lessons with Balakirev. (We can only imagine how Mussorgsky’s parents must have reacted to that bit of “career news”!)

Among the members of the The Five, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov became particularly close. They bonded during the winter of 1871 and 1872, when they shared a single room and composed on the same piano and at the same table. They arranged things so that Mussorgsky – who was composing his opera Boris Godunov – would work in the morning. He would then clear out, and Rimsky-Korsakov – who was working on his opera The Maid of Pskov – would compose there in the afternoon.

Mussorgsky’s fame rests on a remarkably small number of works: a series of superb songs, his operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina, and the instrumental works St. John’s Night on Bare Mountain and Pictures at an Exhibition.

Mussorgsky’s masterwork is his opera Boris Godunov, which has had – nevertheless – a rather tortured history. Mussorgsky initially completed Boris in 1869, when he was 30 years old. Unfortunately and most painfully, it was rejected for performance by the Imperial Theaters because it did not feature an important female role:

“How can there be an opera without the feminine element?! Mussorgsky has great talent beyond doubt. Let him add one more scene. Then Boris will be produced!”

Mussorgsky went back to the drawing board and completed his revised version of Boris Godunov – now replete with a role for prima donna and other, expanded female roles – in mid-1872. However, for reasons never made clear, this version was rejected for performance as well!

This is where Mussorgsky’s friends took matters into their own hands. At their expense, they staged three scenes from the opera at the Mariinsky Theatre on February 5, 1873. This “preview” was so fantastically successful that the Imperial Theaters had no choice but to produce Mussorgsky’s revised version of the opera, which received its premiere on January 27, 1874.

End of story?

Hardly.

While the audience at that sold-out premiere gave Mussorgsky 20 curtain calls, the critics blasted the opera and its composer. The opera’s conductor Eduard Nápravník insisted on sweeping – even savage – cuts to the opera, which Mussorgsky, in his desperation, sanctioned. The cuts didn’t do Boris any good. The critic Herman LaRoche wrote:

“The general crudity of Mr. Mussorgsky’s style, his passion for the brass and percussion instruments, may be considered to have been borrowed from [Alexander] Serov. But never did the crudest works of the model reach the naive coarseness we note in his imitator.”

And talk about a stab in the back! Mussorgsky’s erstwhile friend and colleague, fellow Five member Cesar Cui, wrote:

“Mr. Mussorgsky is endowed with great and original talent, but Boris is an immature work. Its main defects are in the disjointed recitatives and the disarray of the musical ideas. The real trouble is his immaturity, his incapacity for severe self-criticism, his self-satisfaction, and his hasty methods of composition.”

Peter Tchaikovsky was even less kind:

“I have studied Boris Godunov thoroughly. Mussorgsky’s music I send to the devil; it is the most vulgar and vile parody on music.”

(At another time Tchaikovsky wrote:

“[Mussorgsky] is devoid of any urge towards self-perfection, blindly believing in the ridiculous theories of his circle. He flaunts his illiteracy, takes pride in his ignorance, mucks along anyhow, thoughtlessly believing in the infallibility of his genius.”)

Mussorgsky’s reputation immediately following his premature death was that of a brutally crude and unsophisticated composer. In the 1905 edition of The Oxford History of Music, Edward Danreuther wrote:

“Mussorgsky appears willfully eccentric. His style impresses the Western ear as barbarously ugly.”

In fact: Mussorgsky’s music might have fallen into oblivion if not for the efforts of his friend and fellow “Fiver”, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

Rimsky-Korsakov was distraught when Mussorgsky died of acute alcoholism on March 28,

Yes: a good friend. But many observers now feel that in his attempt to “clean up” Mussorgsky’s works, Rimsky-Korsakov glossed over their essential and purposeful roughness. In his memoires, Rimsky-Korsakov was a bit defensive when discussing what he found in Mussorgsky’s manuscripts:

“All were in exceedingly imperfect order; there occurred absurd, incoherent harmonies, ugly part-writing, strikingly illogical modulations [or a] depressing absence of any at all, ill-chosen instrumentation; in general a certain audacious dilettantism, at times moments of technical dexterity and skill but more often of utter technical impotence. However, these compositions showed so much talent, so much originality, offered so much that was new and alive, that their publication was a positive obligation. But publication without a skillful hand to put them in order would have made no sense save a bibliographic-historical one. There was a need of an edition for performances, for practical artistic purposes, for making his colossal talent known, and not for the mere studying of his artistic sins.”

Mussorgsky was a compositional “primitive”, a composer whose compositional roughness gives his music its black-earthed muscle, it “Russian-ness.”

However, the question remains: was that roughness purposeful or simply the result of Mussorgsky not knowing any better? For Rimsky-Korsakov, it was a flaw. But for many others it is a reflection of a composer of genius who chose not to be limited by what he considered to be arbitrary rules.

Among those who worshipped Mussorgsky’s artistic independence was the spectacularly original and influential French composer Claude Debussy, who, twenty years after Mussorgsky’s death stated that his music was:

“spontaneous and free from arid formulas [making him] something of a god in music, who will give us a new motivation to rid ourselves of ridiculous restraints.”

For lots more on Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, How to Listen to and Understand Opera.

Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More