We mark today the 258th anniversary of the marriage of Joseph Haydn to Maria Anna Aloysia Apollonia Keller in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in the great city of Vienna. The groom was 28 years old and his blushing bride 31.

We contemplate the institution of marriage.

Marriage is like swinging a golf club: it looks so easy on TV. But when we actually pick up a golf club and/or get married, we learn soon enough how very, very, very challenging marital reality can be.

I know of what I speak. I am in my fourth marriage, though I’d hasten to point out that that’s not because I’m a disagreeable monster (although my first wife, from whom I am divorced, might beg to disagree), but because I’ve lost two wives to cancer.

When I married for the fourth and final time to Dr. Nanci Tucker – a real doctor, one who can write a prescription – my old friend and colleague Dr. Frank LaRocca – not a real doctor; he cannot write a prescription – said to me “you win”. You see, Frank has been married three times, and with my fourth marriage he figured that the person with the greatest number of marriages was the winner. I disagreed: to my mind, the fewer the number marriages, the bigger the winner. To my mind, folks who have been married but once and have managed to stay married for the duration are the biggest winners of all. Sure: there are good times and bad times; good years and bad years; ups and down and everything in between. But if you can stay married to that first spouse and grow up together and grow old together, you are a winner in my book.

Now, I would hazard to guess that we all know at least one married couple that has stayed together – through thick and thin – despite the fact that they do nothing but make each other miserable. We would suppose that such a thing is less common today than in earlier times, when obtaining a divorce bordered on the impossible.

Sadly, such was the case of Joseph Haydn’s marriage to Maria Anna Aloysia Keller, who Haydn came to refer to as “that infernal beast!”

There’s no kind way to put it. Haydn’s marriage was a disaster, a fiasco, a bomb, a bust, a legendary failure: the Ford Edsel, the eight-track cartridge, the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 of marriages, a marriage that sank faster than a submarine with screen doors, that fizzled out more violently than a tube full of Mentos in a liter bottle of Diet Coke; the grandmother of rotten marriages, the single greatest torment in Haydn’s long life.

Here are the particulars.

Sexually, Joseph Haydn was a regular, red-blooded, down-the-middle-of-the-plate heterosexual guy. Unfortunately, until his mid-twenties he had had almost no contact with girls or women his age. From the age of 8 to 17 he had been cloistered away as a choirboy at Vienna’s St. Stephen’s cathedral, and consequently, he had no contact or experience with girls of any sort at a time when he should have been learning the rules of sexual warfare.

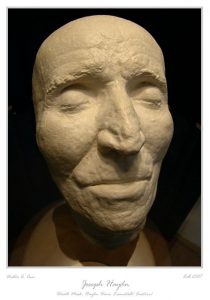

His poverty and workload during his years as a freelancer – from the age of 17 to 25 – precluded almost entirely any social contact with women his age. It didn’t help either that Haydn – who was just about the nicest, sweetest guy any of us will ever meet – was fabulously unattractive: undersized, with bow legs too short for his body; smallpox scarred, socially awkward, and with an aquiline schnozzola (meaning a hooked nose) that occupied multiple time zones. By his early twenties, Haydn was (quite understandably) desperate to “experience” a woman, provided that experience was acquired in a manner consistent with his devoutly Catholic religious and moral beliefs, which means through matrimony.

Among the twenty-something Haydn’s students in Vienna were the two daughters of a wigmaker named Johann Peter Keller. Haydn fell head over heels in love with the younger one, a reportedly beautiful and vivacious girl named Therese who was born in 1733 and was thus a year younger than Haydn. However, her parents insisted that Therese devote herself to the Church, and to that end she entered into the nunnery at the Convent of St. Nicholas.

Haydn was heartbroken, but he stayed in touch with the Keller family. When he secured his first full-time appointment in 1758 – and could finally boast of both a good position and a steady income – the wigmaker Johann Peter Keller decided to secure Haydn for his other daughter, Maria Anna. Maria Anna Aloysia Apollonia was three years older than Haydn. She was, by every account that has come down to us, exceedingly unattractive in both person and personality.

We do not know what sort of pressure – begging, promises, noogies – the Kellers brought to bear on Haydn; whatever they said or did, it worked, because against every shred of better judgment Haydn married their daughter Maria Anna. Despite his inexperience with women, Haydn’s naiveté regarding Maria Anna remains something of a mystery, because he was a genuinely good judge of human nature who showed himself – time and time again – to be shrewd and crafty in his dealings with people. Perhaps Maria Anna, with the prospect of living out her life as an old maid staring her full in the face, was on her best behavior until her vows were given. For his part, it would seem that Haydn just wanted to get married and get . . . um . . . “conjugated”, and with Therese unavailable the actual partner really didn’t make much difference.

We can safely assume that Haydn believed marriage was going to provide him with a comfy life, a peaceful home, and lots of children (which Haydn adored). Strike three, young dude. We are told that:

“Maria Anna was quarrelsome, jealous, bigoted, not even a good housekeeper, and to Haydn’s particular dismay, a spendthrift.”

As for children, there were none, prompting Haydn to remarked:

“My wife was unable to bear children, and for this reason I was less indifferent towards the attractions of other women than I might have otherwise been.”

No surprise: both Haydn and Maria Anna eventually indulged in extra-marital shenanigans, which is entirely understandable given that divorce was not an option for a Catholic couple in mid-eighteenth century Austria.

However, what bothered Haydn most about his erstwhile “wife” was her complete lack of interest in or appreciation of his music. Haydn bitterly complained:

“She doesn’t care a straw whether her husband is an artist or a cobbler.”

Haydn’s friends and colleagues have reported that Maria Anna, out of pure malice, would use her husband’s handwritten manuscript scores as parchment paper: to line the inside of her pastry pans; or she would shred them, then use those twisted shreds to curl her hair.

Yes, I know, it presumably takes two people to make a good marriage and two people to make a rotten one. But in reading the literature it seems pretty clear that Haydn would have been relatively content had Maria Anna shown him a modicum of emotional and physical affection and had shown some interest in his music.

By the 1770s, Haydn and his wife were completely estranged, and spent as little time in each other’s presence as was possible. By the 1780s, their marriage had, for all intents and purposes, ceased to exist.

In 1797 – at the age of 65 – Haydn bought a house in what was then the Vienna suburbs (and which today is in the middle of the city!) with money earned from his two triumphant residences in England. To Haydn’s great pleasure, his wife was almost never there; she suffered from severe rheumatism and lived in the spa town of Baden, taking – as it were – a permanent cure. It was there that she died on March 20, 1800.

Joseph Haydn was, almost certainly, among the merriest widowers of all time.

He died “blissfully and gently” in his house nine years later, shortly after midnight on May 31, 1809. His last words were “Children, be comforted. I am well.” It was a reference, I think, not to his physical health, but rather, his spiritual health.

For lots more on the life of Joseph Haydn, I would direct your attention to my Great Masters biography of Haydn published by The Great Courses.

Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More