(What, you don’t “like” my title? Please, don’t get testes about it.)

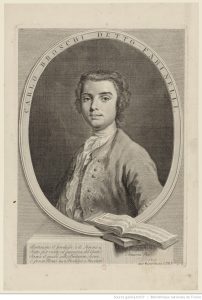

We note the death on September 16, 1782 – 237 years ago today – of one of the greatest opera singers to have ever lived, the celebrated Italian castrato Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi, who went by the stage name of “Farinelli”.

How often in our search for cultural equivalence – how tiresomely often – do we hear statements on the lines of, “Like, Mozart was, like, the rock star of his time.”

No, like, he wasn’t. We’ve talked about this before, and here I’ve brought it up again. Composers of concert music, even one as flamboyant as Wolfgang Mozart, never had the fame, notoriety, visibility, wealth, and necessary sexual charisma for what we, today, would consider the prototypical “rock star.”

Let us consider the exaggerated sexuality that is the first and perhaps most important aspect of “rock stardom.” On one hand there are the alpha males, the walking phalluses with tin foil wrapped cucumbers stuffed into their leather pants (thank you for that enduring image, Spinal Tap), rockers who reduce their female audience members to whimpering pools of fluid: Elvis, Mick, Keith, Paul (the “cute” one!), James Morrison, Kurt Cobain, Gene Simmons, and Jared Leto, to name just a few.

Then there are their female equivalents, stunningly beautiful caricatures of the perfect sex machine; dressed like high-end hookers, women in (seemingly) complete control of their sexuality, whose pseudo-copulatory, strip joint gyrations on stage drive their male audience members (pun intended) to near madness with desire: Grace Slick, Debbie Harry, Tina Turner, Gwen Stefani, Joan Jett, Britney Spears, Stevie Nicks, Amy Winehouse, Pink, to name just another few.

Most intriguing, I think, are the pan-sexuals: those rock stars whose provocative, flamboyant, often outrageous, sometimes androgynous personas have imbued them with the reputation of erotic taboo breakers: David Bowie, Michael Jackson (may he rest in pieces), Madonna (Madonna Louise Ciccone), Prince (Prince Rogers Nelson), Freddie Mercury (Farrokh Bulsara), Elton John (Reginald Kenneth Dwight), and Lady Gaga (Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta), for example.

In a critique, the feminist and social critic Camille Paglia asserted something about Lady Gaga that can be applied to all of the pan-sexuals listed above; that she is “an identity thief: a mainstream manufactured product.”

Well, duh. In fact, Ms. Paglia takes nothing away from the good Gaga by pointing out that she is part of a mainstream music industry, one that goes back nearly 400 years, an industry for which provocation, flamboyance, androgyny, and sex, sex, and more sex sells. That “industry” was created in Italy and goes under the blanket designation of “opera”.

An opera is stage play in which the words are intensified a gazillion fold (give or take) by setting them to music. Since the birth of opera around 1600, and particularly since opera went public in 1637, it has been acknowledged that nothing puts derrieres in seats (and money in the box office) better than sex, violence, religious controversy, sex, great costumes, beautiful singing, sex, and celebrity: the celebrity of the singers themselves.

Who were the real “rock stars” of the seventeenth and eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries? Opera singers, that’s who. And who were the biggest, baddest, most flamboyant, richest and most talked about “rock stars” among them; who were the David Bowies, the Michael Jacksons, the Freddie Mercurys, Elton Johns, the Princes and the Lady Gagas: the androgynous ones?

In the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it was the Italian castrati: male sopranos whose testicles had been forcibly removed before puberty (do any of us think the children thus mutilated – without anesthesia, we might add – did so voluntarily?), who then underwent an unimaginably rigorous training regimen for upwards of a decade in order to develop their presumably “permanent” soprano voices. Notorious for their egos, their flamboyance, their glamour, their tantrums, their virtuosity, and the sexual ambiguity they projected (the dudes were, after all, men singing in the soprano range), the Italian castrati were the direct ancestors of such modern cross-sexual performers as David Bowie, Michael Jackson and Lady Gaga.

Though it was presumably illegal to castrate pre-pubescent boys in sixteenth to eighteenth century Venice, Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Naples, the fact remains that “gelding parlors” could be found in all of these cities. It was a case of “don’t ask, don’t tell”: there was a tremendous demand for castrati on the Italian stage, particularly during their glory days between 1650 and 1800, when both male and female roles were entrusted to them. The vogue for castrati was initially due in part to a shortage of female singers and the fact that in many parts of Italy, including in Rome, women were forbidden to appear on a public stage. But during the eighteenth century, when there was no shortage of high-end women singers, the castrati still maintained their strangle-hold over Italian opera because of their musical and vocal superiority.

The Voci Bianche

You see, there was a qualitative difference between castrati and female sopranos. The castrati – who were known as the voci bianche, literally the “white voices” – had larger, more powerful and more brilliant voices than women, and could continue to sing professionally for as many as forty years. The castrati were also perceived as “exotics”: they didn’t just sound different than other men (and women), but looked different as well: they tended to be considerably taller on average, they lacked facial hair, and they were incredibly loose-limbed in their movements, a result of the lack of testosterone in their bodies.

These guys were the most popular and glamorous stars of their time, and the material rewards for a successful career were so great that even the slightest indication of vocal talent led many parents to emasculate their young sons in the hopes of turning him into . . . well, a real soprano. (Speaking for myself, I wish I could go back in time in order to tell all the boys born in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Italy not to sing in front of an adult under any circumstances.) Sadly, for the vast majority of these poor, snipped boys, there was added insult to injury: neutered though they were, most of their voices changed at puberty anyway. As a result, according to the contemporary English music historian Charles Burney, one saw in every Italian city numbers of these unfortunate men, “without any voice at all, or at least without one sufficient to compensate for such a loss.”

The single most famous of all the Italian castrati was Carlo Broschi, who performed under the one-word stage name of “Farinelli”. He was born on January 24, 1705 in Andria (what today is Apulia), a city located in the “heel” of the Italian boot. Carlo’s father Salvatore was a composer and the music director of Andria’s cathedral. Upwardly mobile, the family moved to Naples in 1711, when Carlo was six. It was there that the young Carlo, who was already showing talent as a singer (oh NO!), began to study singing with the most famous singing teacher in Naples, the composer Nicolo Porpora.

We do not know exactly when “it” happened. Carlo’s father Salvatore died unexpectedly in November of 1717 at the age of 36, which spelled economic disaster for the family. Consequently, it is generally believed that this is what prompted the Broschi family to put Carlo under the knife, despite his relatively advanced age of 12. (As was typically the case, an “excuse” had to be found for undergoing castration; it is said that the Broschi family claimed that Carlos’ emasculation was necessary as his testicles had been crushed and thus irreparably damaged in a fall from a horse. Right.)

Carlo’s intense study under Nicolo Porpora yielded almost immediate dividends. He made his debut at 15, and by 1722 – at the age of 17 – he had achieved fame across Italy and was singing in Rome. With his Vienna debut in 1724, that fame quickly spread across Europe. In 1726, the composer and flutist Johann Joachim Quantz heard him and subsequently wrote:

“Farinelli had a penetrating, full, rich bright and well-modulated soprano voice, with a range from A below middle C to the D two octaves above middle C. [Time out. In fact, Farinelli’s range was greater than that; he could comfortably sing from the F below middle C to the F 2½ octaves above middle C. Quantz continues.] His intonation was pure, his trills beautiful, his breath control extraordinary and his throat very agile, so that he performed the widest intervals quickly and with the greatest ease and certainty. Passagework and all kinds of melismas were of no difficulty to him. In the invention of free ornamentation in adagio he was very fertile.”

Quantz’ description is that of a transcendent vocal virtuoso. And while a great voice alone is sometimes not enough to guarantee success on the opera stage, Farinelli had the looks, acting ability, stage presence, and sexual charisma to back up his voice.

A brilliant, tireless, over-the-top-flamboyant performer, Farinelli was worshipped by both the cognoscenti and the general, opera-going public alike. His sexual exploits and conquests were the talk of all Europe. (Emasculation did not necessarily render castrati incapable of sexual performance, although the sexual prowess with which they were credited was more the stuff of tabloid gossip than reality. Nevertheless, in a birth-control challenged, hyper status-oriented social world, a castrato was a safe and sought after pillow partner among those upper-crust ladies who could afford to have one). Like many high-visibility performers of our own time, Farinelli parlayed his insane popularity as a singer into major political clout. He was embraced as a friend by emperors and princes. He was, for 24 years, the confident of two successive Spanish Kings: Philip V and Ferdinand VI. He was the hero of contemporary gossip and the object of urban legends. In what might be considered the most appropriate of all his many honors, he is the title subject of three operas and a motion picture.

He retired to the Italian city of Bologna in 1759 and lived there for the remaining 23 years of his life. His palatial home, filled in his lifetime with art treasures and his adored collection of keyboard instruments and violins (including an Amati and a Stradivarius), eventually became the corporate HQ for a sugar company. Badly damaged during World War Two, the house was demolished in 1949. But Farinelli’s reputation has never been damaged, and his standing as the greatest singer of the castrato era will likely never be challenged.

For lots more on the history of opera and the role of the castrati, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, How to Listen to and Understand Great Opera, which can be examined and downloaded here at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More