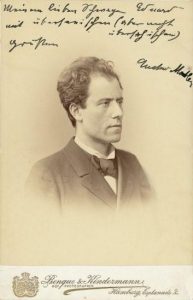

On October 8, 1897 – 121 years ago today – Emperor Franz Joseph I of the Dual Monarchy of Austria and Hungary officially named Gustav Mahler Director of the Vienna Court Opera.

For the 37 year-old Mahler, it was the culminating moment in what had been (and sadly, what would continue to be) a very difficult life. He was born on July 7, 1860 in the village of Kalischt, in central Bohemia, in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is today part of the Czech Republic. Mahler’s was a lower middle class Jewish family; they spoke German and were thus a double-minority among their predominately Catholic, Czech-speaking neighbors.

Mahler grew up abnormally sensitive and morbidly imaginative; a constant witness to his father’s brutality and his mother’s helplessness. According to Henry Raynor:

“All the Mahler children were incapable of facing reality and suffered from a sense of inevitable tragedy.”

Young Gustav’s sense of morbid tragedy was also a function of the disastrous mortality rate of his siblings. Of the fourteen Mahler children, seven died in infancy and only four (including Gustav) lived into full adulthood.

Mahler’s musical talent was prodigious. He attended the Vienna Conservatory from 1876 to 1878, where he studied piano and composition. An indifferent student, his harmony teacher later told Gustav’s wife Alma that “Mahler always played truant, and yet there was nothing he couldn’t do.”

Well, in fact, there was indeed something Mahler wasn’t able to do: he wasn’t able to figure out how to make a living as a composer. So, to what he later claimed was his eternal regret, he began conducting opera for a living. Had he trained as a conductor? No. Had he ever composed an opera? No. (And he never did, despite being a brilliant composer for both the orchestra and the voice and the greatest opera conductor of his time.) But financial necessity can make us all do the darndest things, and thus Mahler began his conducting career in 1881 at the age of 21, conducting operettas in the summer resort town of Bad Hall in northern Austria. For Mahler, it was almost certainly a case of “fake it till you make it”, though he didn’t have to “fake it” for long: he discovered, almost immediately, that he had a real flair for conducting. From Bad Hall he quickly moved on to the Landestheatre in Laibach (1881); and then the Stadttheatre in Olmütz (1883). A succession of posts followed, each one marking a step up from the last: the Kassel Opera (1883); the Landestheatre of Prague (1885); the Neues Stadttheatre in Leipzig (1886); the Royal Hungarian Theater in Budapest (1888); the Hamburg Stadttheatre (1891, where at the height of the season Mahler was conducting nineteen different operas every month!).

At each stop, Mahler set about reforming the various companies to his standards, whether management wanted him to or not. Soloists, choruses and orchestras found themselves exhaustively rehearsing operas they believed they already knew for hours upon hours. Mahler was a small, pale, merciless tyrant. Yes: the singers, choruses, and orchestras loathed him. But audiences loved him wherever he went because he created a frisson – an excitement – that no one could deny.

To his everlasting unhappiness, Mahler had to squeeze his composing into the occasional breaks during the season and during the summer. On one hand, we would wish that he had had more time for composing, yet on the other, there’s no doubt that his limited composing time forced on him an intensity and spontaneity as a composer that he otherwise might not have experienced.

The fall of 1896 marked Mahler’s fifth anniversary at Hamburg. For Mahler, who loved to identify himself as Ahaseurus, the Wandering Jew, five years was forever. Besides, the bloom had come of the rose in Hamburg: his endless fights with management and management’s exasperation with Mahler’s endless intransigence convinced Mahler that it was time to move on.

He got word was that Wilhelm Jahn, the Director of the Vienna Opera, was losing his eyesight and would soon have to step down from his position. O.M.G.; Mahler’s saliva glands went into overdrive. The Vienna Opera, the single most prestigious musical institution in all of Europe. Could the job be his? Could he rule the musical roost in the same city in which he had lived like a pauper during his student days?

The story of Mahler’s application, audition, and ascension to the position of Music Director of the Vienna Opera is a long and complicated one. Here are the highlights.

Fall, 1896: Mahler went about lobbying just about everyone he knew who might help him to overcome the seemingly insurmountable obstacles he knew he would face in landing the job.

In January 1897, Mahler was informed that “under present circumstances, it is impossible to engage a Jew in Vienna.”

But also in January 1897, Mahler’s candidacy gained the support of Eduard Hanslick, Vienna’s most influential music critic and a close friend of Johannes Brahms.

February 23, 1897: realizing that with Hanslick’s active (and Brahms’ tacit) support he actually had a chance of getting the job, Mahler converted to Catholicism and was baptized at the Kleine Michaeliskirsche in Hamburg. (Mahler immediately told his friend Ludwig Karpath that: “I do not hide the truth from you when I say that this action, which I took from self-preservation and which I was fully disposed to take, has nevertheless cost me a great deal.”)

On April 8, 1897, Mahler was appointed one of the four conductors of the Vienna Opera. Conversion or no conversion, the anti-Semitic Viennese press went wild. Two days later, on April 10, 1897, an article in the Deutsche Zeitung attacked what it called “The frightening Jewification of art in Vienna. Is a Jew capable of defending our great music, our great German opera if, like Mahler, he has just been baptized a few weeks before?”

The anti-Semitic kerfuffle changed nothing, and on October 8, 1897 – 121 years ago today – Gustav Mahler was appointed by Emperor Franz Joseph Director of the Vienna Court Opera; thereby Mahler derived his authority from the Emperor himself. That the 67 year-old Emperor Franz Joseph and his advisors had placed a 37 year-old Bohemian-born Jew at the head of the single most important cultural institution in the Empire reveals just how liberal the Habsburgs in general, and Franz Joseph in particular, had become. The Jewish middle-class had indeed become a backbone of late nineteenth-century Viennese society, and Jewish artists and thinkers – including Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Hugo Hoffsmanthal, Arthur Schnitzler, Max Reinhardt, Stefan Zweig, Sigmund Freud, and Theodor Herzl – were central players in Viennese intellectual life. That the Austrian Empire – with Vienna as its capital city – had been in political decline for a hundred years is well known, eclipsed by the growing power of Prussia and, eventually, a united Germany. But Austria’s political decline was well concealed by Vienna’s prosperity and its brilliant culture, particularly its musical culture.

By the turn of the twentieth century, as the political problems facing the Austrian Empire became increasingly insoluble, we are told by Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de la Grange that:

“The dominant Viennese characteristics were a sort of pessimism, a hedonism, a love of spectacle, and an amused, blasé, and often morbid skepticism.”

It was into this conservative, liberal, Jewish-empowered, anti-Semitic, music-crazed, opera-insane, genuinely schizoid environment that Gustav Mahler, himself a man of a thousand moods and faces, arrived to take over the opera in 1897. On his first day as Music Director, he did what he always did when taking up a new position: he wrote out his resignation letter, put it in an envelope, and placed it in the top drawer of his desk. Mahler took a certain perverse pride in knowing he was prepared to quit any job at any time. Ten years would pass before he dusted off the letter and submitted it; it’s quite a story but one for another time!

For lots more on Mahler and his magnificent symphonies I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, “The Symphony” and Great Masters: Mahler – His Life and Music.

Listen on the Music History Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More