“She had only to walk on stage to reduce the audience to a melting blob”

On August 26, 1976 – 43 years ago today – the German-born soprano, opera star, lieder singer, movie actress, internationally renowned teacher, music historian and author, published poet, painter and illustrator Lotte Lehmann died in Santa Barbara, California at the age of 88.

In 2004 and 2005, I had the honor of speaking at The Music Academy of the West in Montecito, California, just east of Santa Barbara. The Academy, which was founded in 1947, is one of the great summer music conservatories and festivals in the world. It is also among the most beautiful music facilities anywhere. Perched on over ten acres of beachfront property in the beyond-toney enclave of Montecito, the Academy occupies the former site of the Santa Barbara Country Club. (For our information, along with The Music Academy of the West, other residents of Montecito include Drew Barrymore, Patrick Stewart, Rob Lowe, Al Gore, Oprah Winfrey, Jeff Bridges, Gwynwth Paltrow, and Kirk Douglas. The median price for a house there is a cool four million dollars. Heaven knows how much those ten-plus acres on which the Music Academy sits are now worth!)

My presentations at the Academy took place in the main concert hall, a 300-seat theater called Hahn Hall, and the post-lecture receptions were held in a magnificent, Mediterranean Revival-styled room called Lehmann Hall. I inquired as to the name of the room and was told that it was named for one of the principal founders of the music academy, the soprano Lotte Lehmann. My brain preceded to short-circuit in a manner unusual then but rather more often today, and I responded on the lines of, “Wow. A performance space named for Rosa Klebb!” (“Rosa Klebb” was the SPECTRE agent in the second James Bond film From Russia With Love, a Soviet bloc harridan who killed her victims with a poisoned blade that would emerge from the toe of her right shoe. She was played by the Vienna-born Tony Award-winning singer and actress Lotte Lenya. Lenya rose to fame playing Jenny in the original Berlin production of Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, with music composed by her husband, Kurt Weill.)

With great tact, the lovely lady with whom I was talking gently observed that the room in which we were standing was named for Lotte Lehmann, and not, marvelous though she was as Agent Klebb, Lotte Lenya.

Duh.

The founding mothers and fathers of the Music Academy of the West were an impressive bunch, and include along with Lehmann the conductor Otto Klemperer, the violinist Roman Totenberg, the pianist and harpsichordist Rosalyn Tureck, the operatic baritone John Charles Thomas, and the composers Ernest Bloch, Darius Milhaud, Roy Harris, and Arnold Schoenberg (Schoenberg was the Academy’s first composer in residence). Impressive, yes, though not a one of them has a hall named after him or her except Lehmann. That’s because Lehmann was instrumental (no pun intended) in the founding of the Academy; she was a resident of Santa Barbara and after her retirement from the stage in 1951 she taught there for many years. How this German-born diva got to Santa Barbara, and what she accomplished along the way, should be an inspiration for all of us.

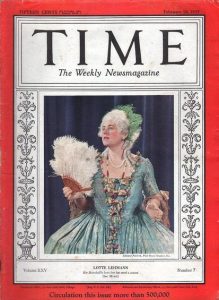

She was born on February 27, 1888 in Perleberg, in the northeastern German state of Brandenburg, midway between Berlin and Hamburg. Trained in Berlin, she made her operatic debut in Hamburg in 1910, at the age of 22. In 1916 she joined the company of the Vienna Court Opera (later the Vienna State Opera), where she quickly established herself as one of the premiere singers of her generation. She sang everything: Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Meyerbeer, Offenbach, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, Bizet, Gounod, Massenet, Puccini, Mascagni, Richard Strauss, Korngold; the list goes on; I shall not. She sang everywhere and with everyone; such was her fame (and the affection with which she was held) that she appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on February 15, 1935.

Lehmann was not just a great singer but a great actress as well, someone who appears to have been universally admired by her peers (no small thing for an operatic diva). When Enrico Caruso heard her sing for the first time, he embraced her and delivered what was, for him, the highest possible compliment:

“Ah, brava, brava! Che bella magnifica voce! Una voce Italiana!” (“Ah, wonderful, wonderful! What a beautiful, magnificent voice. An Italian voice!”)

Lotte Lehmann was Richard Strauss’ favorite soprano, hands down. Her most famous Strauss role was the world-weary Marschallin from Der Rosenkavalier. Of Lehmann’s portrayal of the Marschallin, Harold Schonberg – the often-curmudgeonly music critic of The New York Times – wrote:

“Talking about it, strong men snuffle and break into tears. They discuss her with the reverence of a legal mind talking about Justice [Oliver Wendell] Holmes, or a baseball connoisseur analyzing [Rogers] Hornsby’s form at the plate, or the old‐timer who remembers Toscanini’s Wagner at the Metropolitan Opera. In short, she was The One: unique, irreplaceable, the standard to which all must aspire. . . She generated love, [and] had only to walk on stage to reduce the audience to a melting blob.”

The American journalist and novelist Vincent Sheean was haunted by Madame Lehmann:

“The peculiar melancholy expressiveness of her voice, the beauty of her style in the theater, the general sense that her every performance was a work of art, lovingly elaborated in the secret places and brought forth with matchless authority before our eyes, made her a delight that never staled. She was like that Chinese empress of ancient days who commanded the flowers to bloom—except for Lotte they did.”

A great story. In August of 1936, Lehmann was in Salzburg, looking for a villa to rent. During the course of her search, she overheard children singing in the garden of a nearby home. Stunned by what she heard, she knocked on the door, and in doing so discovered the Trapp Family Singers, who would be made famous by The Sound of Music. She told the children’s father that his family had “gold in their throats” and strongly suggested that they enter the Salzburg Festival contest for group singing the following night. However, the father – Baron Georg von Trapp, every inch the haughty aristocrat – told her that performing in public was beneath the dignity of a von Trapp and was thus out of the question. But this was Lotte freakin’ Lehmann he was talking to and her enthusiasm won the day. The Baron relented, and the Trapp Family performed in public for the first time the following day.

Lehmann made her American debut in 1930 and thereafter returned to the United States every year. In 1937, sickened by the rise of Nazism (Michael Kater’s excellent biography of Lehmann is entitled Never Sang for Hitler), she emigrated to the United States and became an American citizen in the early 1940s.

In 1948 Lehmann made her film acting debut in a movie called Big City, which starred Danny Thomas (who was born Amos Alphonsus Muzyad Yakhoob, the child of Lebanese immigrants, who in the movie plays a Jewish Cantor), Robert Preston, George Murphy and Margaret O’Brien. In the movie, Lotte Lehmann – a Christian Prussian – plays Danny Thomas’ Jewish mother, a character named “Mama Feldman.” Ah, Hollywood.

(For our information, Lehmann’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1735 Vine Street is marred by a misspelling: “Lottie” Lehmann.)

Later in her life Madame Lehmann said that: “there was no art form that was safe from me.”

Truer words were rarely spoken. She was a prolific writer, whose first collection of poetry was published in the early 1920s; whose novel, Eternal Flight, was published in 1937, and whose first memoir was published in 1938. Among her many additional publications were books on song and operatic interpretation, a memoir of Richard Strauss, and a second book of poetry, published in 1969.

Lehmann was also a skilled painter and illustrator, and a loving and passionate teacher, who numbered among her many, many students Grace Bumbry and Marilyn Horn.

She was a true polymath, by any standard.

We close with a story from Alden Whitman’s New York Times obituary of Lehmann, an obit that appeared on August 27, 1976, the day after her death:

“It was at a lieder recital in [New York City’s] Town Hall in 1951 that Lehmann announced her retirement as a singer. Stepping to the footlight at intermission, she said, ‘This is my farewell recital.’

‘No! No!’ the audience cried.

‘I had hoped you would protest,’ the soprano continued when the shouting had abated, ‘but please don’t argue with me. After 41 years of anxiety, nerves, strain and hard work, I think I deserve to take it easy.’

Then, referring to the aging Marschallin, who gives up her young lover in Der Rosenkavalier, Mme. Lehmann said:

‘The Marschallin looks into her mirror and says, ‘It is time.’ I look into my mirror and say. ‘It is time.’’

Many in the throng wept.

Later, backstage, she remarked:

‘It is good that I do not wait for the people to say: ‘My God, when will that Lotto Lehmann shut up!’”

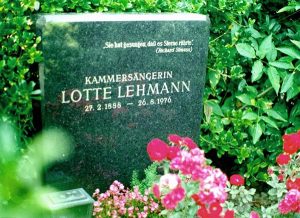

Madame Lotte Lehmann is buried in Vienna’s main cemetery, the Zentralfriedhof. On her tombstone are inscribed the words of Richard Strauss: “Sie hat gesungen, dass es Sterne rührte.” (“She sang, and the stars were moved.”)

For lots more on opera and opera singers, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, How to Listen to and Understand Great Opera, which can be examined and downloaded here at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More