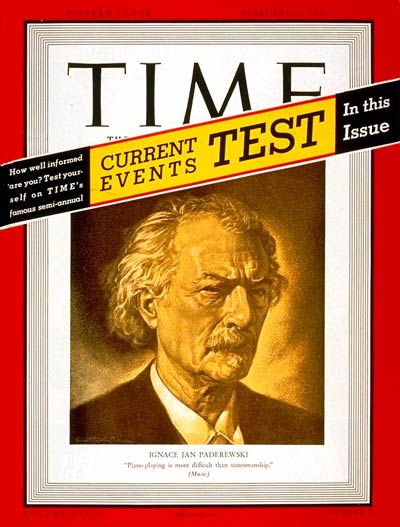

On June 29, 1941 – 79 years ago today – the Polish pianist, composer, philanthropist, vintner, and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski died in New York City. He was 80 years old.

Before moving on to the story of that truly remarkable man’s life, we would grudgingly allot 230 words to a story so wonderfully ridiculous that I’d wager not a one of us could have made it up.

On this day in 2000, Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born 1972) – better known by his stage name of “Eminem” – was sued for $10 million for slander and defamation of character by his mother Debbie Mathers-Nelson (born 1955). She had taken offense from a line in Eminem’s breakthrough single “My Name Is” (from his 1999 debut album The Slim Shady LP). The offending line? “My mom smokes more dope than I do”.

For his part, the rapper maintained that his lyric about his mother was totally true: that she did smoke more dope than he did.

By her conduct during the suit, Ms. Mathers-Nelson provided all the evidence necessary to support her son’s assertion. According to her attorney Fred Gibson “she was the most high-maintenance client I’ve had in my legal career.” At wits end with his client and her stinkin’ law suit, Gibson settled the thing for $25,000. Claiming she had been coerced into settling, Mathers-Nelson attempted to fire Gibson.

But in 2001, the Macomb County, Michigan, Circuit Court Judge Mark Switalski ruled that Debbie Mathers-Nelson was merely attempting to jockey for more money. The judge awarded her attorney Fred Gibson $23,354.25 of the $25k settlement, leaving Ms. Mathers-Nelson with exactly $1645.75 for her trouble.

(Eminem has further asserted that while he was growing up his mother used to sprinkle drugs on his food. Okay; that’s a crazy person.)

On to the life of Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

But first, a little necessary historical background.

Geographically, the country we today call “Poland” came into being in 1945, when the borders of the Soviet Union and Germany were “redrawn” at the conclusion of World War Two. It was not the first time the historical entity known as Poland suffered the indignity of having it’s territory sliced and diced like a cucumber in your Veg-a-matic, although we can hope that it will be the last time.

If any nation can be said to be cursed by its geography, it is Poland. Aside from a relatively small strip of mountains along its very southern border, Poland is as flat as your dining room table, with nary a natural obstacle to separate it from its neighbors. And oh, what neighbors! At the time of Paderewski’s birth on November 18, 1860, those neighbors were the Russian Empire to the east, Prussia to the west, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the south. Like living between Hannibal Lector, Jeffrey Dahmer, and the human flesh-eating Letin clan of Papua, New Guinea, what was once known as “the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth” was surrounded by rapacious predators that threatened constantly to bite off chunks of its territory when circumstances permitted.

The so-called “partitioning” of Poland began in 1772 when, for diplomatic reasons, it became advantageous for Tsarina Catherine the Great’s Russia to begin the process of “breaking up” the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Poland, with its complete lack of defensible borders, had no choice but to acquiesce.

“Partition”: it’s such a benign word. Let’s call it for what it is: piecemeal invasion and annexation. Hunks of Poland were sliced off like roast meat from a spit and distributed among the hungry states around it: Prussia, Russia, and Austria. Prussia and Russia coveted Polish territory for many reasons, though chief among them was that Poland provided a natural buffer between Prussia and Russia. Poor Poland; its geographical location is its curse. Stuck between Prussia and Russia, and then between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and then representing the line between Nato and the Warsaw Pact, the Polish nation and its magnificent people suffered unimaginable destruction and pain right on through the twentieth century.

Two more partitions followed that first one in 1772; one in 1793 and another in 1795. As a result of that “Third Partition” of 1795, so much Polish territory had been shaved off and incorporated into Russia, Prussia, and Austria that an independent Poland simply ceased to exist.

But the Polish people and their culture, language, and shared history did not cease to exist, and their pride and nationalism grew in proportion to the humiliations foisted upon them by the Russians, Austrians and Prussians.

Paderewski was born to Polish parents in a village called Kuryłówka (Kurilivka), which for hundreds of years had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. But at the time of his birth in 1860, it was squarely within the Russian Empire. (No more though; today it is in Ukraine.)

In 1872, at the age of 12, Paderewski matriculated at the Warsaw Conservatory. From there it was on to Berlin, where he studied composition and then to Vienna, where he finished his pianistic education at the hands of the famed pedant, Theodore Leschetizky (1830-1915).

He made his professional debut in Vienna at the age of 27, in 1887; his Paris debut in 1889 and his London debut in 1890. We’ll put it simply: audiences went WILD; they went CRAZY.

We’ll talk more about Paderewski’s pianism and incredible success as a concert artist tomorrow, in my Dr. Bob Prescribes post on Paderewski’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 17. Please, suffice it, for now, the following. He was not the greatest pianist of his time; likely not even in the top ten (or even the top twenty). Yet for the general concert-going public, Paderewski’s name became synonymous with the greatest feats of pianistic virtuosity. Not since Franz Liszt (1811-1886) had audiences gone as routinely gaga over a performing artist as they did Paderewski. Paderewski rode that popular wave like a Maverick’s surfing champ, particularly in the United States, where he was idolized to the same degree as Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley in later decades.

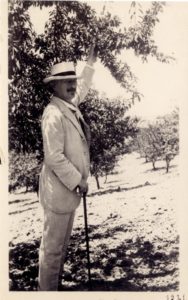

Like “The Chairman of the Board” (Sinatra) and “The King” (Elvis), Paderewski became filthy rich. He was extraordinarily generous with his money; I’ll speak to that in tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post. For himself, he particularly liked to buy real estate, and over the years he owned palatial homes in Poland and Switzerland. But his most impressive real estate venture was in California, a story I cannot resist telling.

Due largely to his incredible popularity, the United States increasingly became a second home for Paderewski. In 1913, at the very height of his fame, he settled in the United States. But not just anywhere; Paderewski had deep pockets and he decided to invest. He headed to Paso Robles on California’s Central Coast, about 180 miles south of San Francisco, which was then (as it remains today) an el-primo grape and fruit growing region. He bought his first parcel of land in February 1914, just five months before the start of World War One. Eventually, his holdings totaled 2864 acres, on which he planted Zinfandel and Petite Syrah grapes, almonds, and a wide variety of fruit trees. We are told that:

“His farming methods and keen interest in wine making transformed the Central Coast agriculture. In addition to his musical and political accomplishments, he also is remembered as a pioneer of vine cultivation in California.”

(Paderewski’s original vineyard is owned today by Bill and Liz Armstrong, the owners of Epoch Estate)

Dude even got it into his head that he might strike it rich drilling for oil. To that end, he purchased an additional 2626 acres of land in Santa Maria, about 40 miles south of Paso Robles, and started drilling. Alas, Paderewski’s Midas touch did not apply to oil exploration; nothing was found and he eventually sold the land in 1933.

But even as he planted, farmed, blended his grapes, and drilled for oil, terrible events were taking place in Polish territory where, once again, geography was its downfall. World War One began in July of 1914, and while, at the time, “Poland” did not exist as a sovereign state, its lands and people were nevertheless ravaged, stuck smack-dab as they were between the belligerent empires of Germany and Austria (on the side of the “Central Powers”) and Russia (along with France and the UK, part of the Triple Entente).

Paderewski became the spokesperson for the Polish National Committee, which was recognized by the Triple Entente as the representative body for a free and sovereign Poland. Paderewski stopped touring as a concert artist and instead, turned his seemingly endless energies to the “dream” of a new and independent Poland. He lobbied the rich, famous, and influential, and gave speeches, made appearances, and attended fundraisers and meetings across America on behalf of Polish independence.

His efforts paid off: the establishment of a “New Poland” became one of President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points”, the statement of principals that formed the backbone of peace negotiations following the war.

The shooting stopped on November 11, 1918. In 1919, Ignacy Jan Paderewski was appointed both the Prime Minister of Poland and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. It was in these capacities that he attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and was a signatory to the Treaty of Versailles, which recognized Polish independence.

For the first time since the third partitioning of Poland in 1795 – 124 years – Poland was an independent nation. It must have been, for Paderewski, a stupendous moment.

Within just ten months, Paderewski’s government held democratic elections to Parliament, ratified the Versailles Treaty, established a system of public education, passed a treaty on protecting ethnic minorities, and dealt with such pressing, post-war issues as unemployment, food shortages, and border disputes. Having held public elections, Paderewski stepped down as Prime Minister, though he continued to represent Poland at the League of Nations. (A fascinating factoid: Paderewski was the only national representative not assigned a translator, as he was fluent in seven languages.)

In 1922, the now 62 year-old Paderewski decided it was time to go back to work. He resigned his political positions and made his comeback appearances first at Carnegie Hall and then in Madison Square Garden, where 20,000 cheering, screaming fans heard him play. He hadn’t lost a bit of his drawing power.

He moved to Switzerland, raked in the moolah and honors (including honorary degrees from USC, Yale, Oxford, Columbia, and Cambridge) and slowly edged towards retirement. Unfortunately, current events were not yet done with Paderewski, and when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939 to initiate World War Two, he was thrust back into public life.

He became the head of the National Council of Poland, Poland’s Parliament-in-exile in London. Paderewski returned to the United States, there to speak and tour and advocate and raise money for the liberation of Poland. But at 80 years of age, his mind and body were not what they once were, and at 11:00 p.m., June 29, 1941, Paderewski died in New York City’s Hotel Buckingham (today The Quin), at 57th Street and Sixth Avenue, a short block away from Carnegie Hall.

On the authority of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt himself, Paderewski was laid to rest in a State Funeral in the crypt of the USS Maine Mast Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Paderewski’s last request was that his body not be returned to Poland until it was a free nation, a condition that was finally met with the fall of communism during the summer of 1989. On July 5, 1992 – in a ceremony attended by Presidents Lech Walesa and George H.W. Bush

– Paderewski’s remains were laid to rest in the Royal Crypt at St. John’s Archcathedral in Warsaw.

But not Paderewski’s heart.

Following the Polish tradition of interring a person’s heart in a place that he or she loved, Paderewski’s heart was removed and initially placed in a crypt in New York’s Cypress Hill Cemetery, which straddles the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. In 1986, the heart was moved to a shrine dedicated to Paderewski’s patron saint, Our Lady of Czestochowa, in Doylestown, Pennsylvania (about 25 miles northwest of Trenton, New Jersey). No doubt: while it might seem an unlikely place for Paderewski’s heart, this shrine was chosen because of its importance to the Polish-American community. Its sister shrine – the Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa near Krakow, Poland – is considered by Polish Catholics to be among the very holiest of places.

Paderewski’s heart rests today inside a bronze sculpture in the shape of a White Eagle, the national symbol of Poland, in the shrine’s memorial hall. In the center of the eagle (at its “heart”, as it were) sits a bust of Paderewski. Below that is a golden heart and a piano keyboard. Paderewski’s heart rests inside his own hollow bust.

Doylestown, Pennsylvania, population, today, circa 8360. We can only guess what Paderewski himself would have thought about having his heart rest, presumably for eternity, in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

For more on Paderewski, make sure to subscribe and read tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes on Patreon.

Listen on Music History Monday

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More