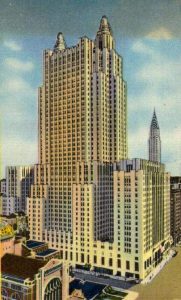

Today we mark a technological event that came and went with hardly a murmur. It was 87 years ago today – on September 17, 1931 – that the RCA Victor Company demonstrated the first long-playing (or “LP”) record to rotate at 33-1/3 rpm (or “rounds per minute”). The demonstration took place at the Savoy Plaza Hotel in New York City. (Because we need to know: the 33-story Savoy Plaza was located at 767 Fifth Avenue. It overlooked Central park at Fifth Avenue and East 59th Street. Built at a cost of 30 million dollars, it opened in 1927 and met the wrecking ball in 1965.)

The tony location of the demonstration aside, listeners were generally unimpressed. The first 33-1/3 rpm records offered no significant sonic improvement over the 78 rpm records that were standard at the time, and despite the fact that more music could be packed onto a disc spinning at 33-1/3 rpm, the new technology eventually fizzled. It wasn’t until 1948, when Columbia/CBS introduced a vastly improved 33-1/3 rpm LP that the new technology took off. (For our information: Columbia/CBS unveiled their new record technology at New York’s Waldorf Astoria on June 18, 1948. Take THAT, Savoy Plaza!)

A fascinating sidelight, one that shows just how short-sighted presumably intelligent corporate leaders can be. The folks at Columbia were certain in 1948 that their new LP was the record format of the future. Wanting to avoid a format war, they offered their technology to RCA Victor, which was their principal competitor. Did the nice people at RCA Victor say thank you, pay the licensing fee, and get on with the conversion to 33-1/3 rpm LPs? No; they did not and it ended up costing them a fortune. Instead of using Columbia’s technology, RCA came out with the seven-inch, 45 rpm record in 1949, and the so-called “battle of the speeds” ensued. But despite the early profitability of 45 rpm records, it was a battle RCA was destined to lose. The maximum capacity for a 45 rpm is 4½ minutes per side; long enough for one song per side. What RCA did with 45’s was refine an old technology, as a standard, 12-inch 78 rpm record could hold between 4 and 5 minutes per side. Yes: these 45 rpm records sounded better, were cheaper, and more portable than 78’s; yes, they served a younger demographic who wanted to purchase “singles”, particularly during the early days of rock ‘n’ roll; and yes, 45’s were ideal for juke boxes. But the standard, 12-inch LP was an entirely new technology. It could hold 22 minutes of music per side, more than enough time for most symphonies or a Broadway show. And Columbia’s “Microgroove” technology assured that their discs were, truly, an order of magnitude better sounding than 45s. In the end, having lost tremendous market share to Columbia, RCA had to make LPs. (And for our information, when they finally got around to it, RCA did it right. The RCA Living Stereo recordings – the so-called “Shaded Dogs” – released between 1958 and 1964 remain among some the best sounding recordings ever made.)

So, on to the title of this week’s Music History Monday post: “I Don’t Know About You But I’ve Always Wondered About That”. That title refers to the record speeds themselves: 78 rpm; 45 rpm; and 33-1/3 rpm: what is the significance of these speeds? Why were they chosen?

With one exception, the choices were essentially random.

Quick background. Until 1896, most recordings were made on cylinders. It was in 1896 that the German-born American inventor Emile Berliner – working in his laboratory in Camden, New Jersey (the future home of RCA Victor) – introduced a technique for cutting grooves into a flat disc that produced significantly better sound than cylinders. Berliner played these discs on a machine he called a “gramophone”, which spun at 78 rpm. Why 78 rpm? According to Patricia Heimers, the public relations director of the Recording Industry Association of America (the RIAA), it was utterly random:

“The inventor [Berliner] needed a motor to drive the record player, and he found one that turned the disc at 78 rpm, although actually it was more like 78.26 rpm. It was a fluke, really; Berliner found a motor that worked at a certain speed and invented the disc to accommodate the motor.”

Ditto the choice by RCA in 1931 for their experimental 33-1/3 rpm records (the introduction of which we’re celebrating today). According to Heimers, “it was essentially an arbitrary number, or more precisely a final compromise between sound quality and length of play.”

It would seem that enough record players were built to accommodate 33-1/3 rpm records (thanks to RCA’s experiment) that when Columbia introduced its own LPs in 1948 it made sense to simply stick with a speed of 33-1/3 rpm.

The speed of a 7-inch, 45 rpm record is the only of the three speeds not to have been randomly chosen but, rather, was arrived at scientifically by RCA. Engineers determined that the most consistent fidelity of a recorded disc occurs when the innermost recorded groove is half the diameter of the outermost recorded groove. In order to achieve these proportions, a 7-inch 45 rpm record has a label 3½ inches in diameter. Given that RCA wanted to match the per-side length of a 12-inch 78 rpm record, a speed of 45 rpm was optimal.

For lots more info and blogs and vlogs and stuff about music, I would invite you to subscribe to my Patreon page.

The Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More