We would acknowledge two date-appropriate musical events before moving on to the pirozhki and potatoes of this post.

On October 28, 1896 – 123 years ago today – the American composer, conductor, and educator Howard Hanson was born in Wahoo, Nebraska. For an up-close-and-personal on Maestro Hanson and his Symphony No. 2, the “Romantic”, I would direct your attention to my Dr. Bob Prescribes post of March 19 of this year. It can be found at my subscription site a Patreon.com/RobertGreenbergMusic.

On October 28, 1957 – 62 years ago today – Elvis (“the pelvis”) Presley’s groin was once again in the news. Having performed a show at the Pan Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, Presley was informed by the Los Angeles Police Department that he would no longer be permitted to “wiggle his hips on stage.” The local press made its two cents known when headlines demanded that Elvis “clean up his act.” The following night – October 29, 1957 – the Los Angeles Vice Squad filmed Elvis’ entire show at the Pan Pacific Auditorium, the better to study the details of his performance.

(Did the L.A. Police and the local press realize that by their actions and statements they guaranteed Elvis standing-room-only audiences at his subsequent appearances? Presley’s agent – Colonel Tom Parker – must have been rubbing his hands together in unalloyed glee: you can’t buy publicity like that; then again, Parker himself was behind the whole thing!)

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6

On to today’s primary topic. We celebrate, on October 28, 1893 – 126 years ago today – the first performance of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, the “Pathétique” in St. Petersburg, with Tchaikovsky conducting. Tchaikovsky’s Sixth was his final symphony and is considered, by consensus, his greatest symphony and among his finest masterworks. Composed between February and the end of August of 1893, Tchaikovsky himself – typically self-critical to a fault – believed the symphony to be his best; while composing it he wrote his brother Modest:

“I am now wholly occupied with the new work . . . and it is hard for me to tear myself away from it. I believe it comes into being as the best of my works. I must finish it as soon as possible, for I have to wind up a lot of affairs and I must soon go to London. I told you that I had completed a Symphony which suddenly displeased me, and I tore

Background

By 1892 – at the age of 52 – Tchaikovsky had attained a level of fame rarely accorded a living artist. He was celebrated and honored everywhere he went. He was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Cambridge University. He received standing ovations from audiences and, like some musical Godfather, was kissed on the hand by musicians. Of the many triumphs and anecdotes of these last years of his life one stands out in particular. In January of 1892 Tchaikovsky traveled to Hamburg, there to conduct a performance of his opera Eugene Onegin. With only one(!) rehearsal allocated to the opera – which was to be sung in German – Tchaikovsk, quickly decided to bow out and hand the baton over to the local conductor, a man, Tchaikovsky wrote:

“Of GENIUS, with a burning desire to conduct the performance.”

This man of genius was the young Gustav Mahler, who conducted what Tchaikovsky called a “positively superb rendering of my score.”

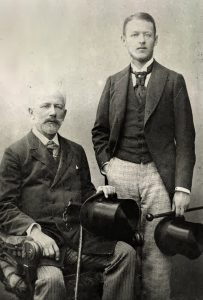

Tchaikovsky dedicated his Symphony No. 6 to his nephew, Vladimir Davidov, who was born in 1871. He was the son of Tchaikovsky’s sister Sasha and her husband Lev and he was known by the rather unlikely nickname of “Bob”. (As unlikely as it would be for yours truly to be called “Vlad”.) The homosexual Tchaikovsky adored Bob, to the point of obsession. By the time he was 13, Tchaikovsky was haunted by Bob and filled with guilty longings for him. A few random excerpts from Tchaikovsky’s diary entries dating to the summer of 1884 paint the picture; (Bob was 13 years old):

“[May 7] I feasted my eyes all day on Bob. How utterly ravishing he looks in his white suit. [May 8] Bob walked with me in the garden, then came to my room. Ah, what a delight Bob is. [May 9] Ah, what a perfect being Bob is. [May 10] A stroll with Bob . . . what a little darling he is! [May 13] Before supper, to his great delight, I played piano duets with my darling, incomparable, wonderful ideal Bob. [May 23] Strange dreams last night; wandering around with Bob. [May 24] In the end, Bob will drive me mad with his unspeakable charms.”

Yes, this should make us all a bit uncomfortable. And while it’s clear that nothing sexually untoward ever occurred between nephew and uncle, it’s also clear that Bob shared his uncle’s sexual proclivities. This helps to explain the extraordinary bond between the two, which only continued to develop as Bob passed through his teens. Tchaikovsky wrote his nephew:

“You are constantly in my thoughts. Through every dark sensation, whether grief, melancholy or anguish, whatever the cloud of my mental horizon, comes a piercing ray of light with the thought that you exist, and that I shall soon see you again.”

It was to Bob that Tchaikovsky first revealed the conception and gestation of his sixth symphony:

“While on my travels I had another idea for a symphony – a program work this time, but its program will remain a conundrum to everyone. Let them guess at it. This program is imbued with subjectivity. While composing it in my thoughts, I often wept a great deal. Then I began writing drafts, and the work was as heated as it was rapid. In less than four days I completed the first movement, and the remaining movements were outlined in my head. There will be much that is new in this symphony where form is concerned, one point being that the finale will not be a loud allegro, but the reverse, a most unhurried adagio. You cannot imagine the bliss I feel after becoming convinced that time has not yet run out and that it is still possible to work.”

On April 5, 1893, Tchaikovsky completed the sketch of his Symphony No. 6. He inscribed on the last page:

“Oh Lord, I thank thee! Today I have completed the sketches in their entirety.”

The orchestration was completed on August 31, 1893. As we previously observed, Tchaikovsky dedicated the symphony to Bob. In a letter to the dedicatee, Tchaikovsky wrote:

“If this symphony is misunderstood, and torn to shreds, I shall think it quite normal, and not at all surprising. It will not be the first time. But I myself absolutely believe it to be the best and especially the most sincere of all my works. I love it as I have never loved any single one of my other musical creations.”

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 was premiered in St. Petersburg on Saturday, October 28, 1893. While Tchaikovsky was greeted rapturously by the audience – his entrance provoked a sustained standing ovation – the symphony was not. On departing the hall, Tchaikovsky reportedly remarked that he expected the Moscow premiere of the symphony, scheduled to take place in three weeks, “to go better.”

Who would have guessed that in just nine days Tchaikovsky would be dead? Tchaikovsky’s sudden, utterly unexpected death on November 6, 1893 remains a controversial subject, one we’ll no doubt discuss at another time.

The fourth and final movement of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony begins with an anguished cry of pain and concludes with what many have interpreted as a death rattle and the nothingness of death. From the moment of his death, the temptation to explain this music as Tchaikovsky’s premonition of his own impending doom has been, for some good people, irresistible. They have described the symphony as a suicide note, as Tchaikovsky’s “requiem to himself.”

This is complete nonsense. For all of his emotional self-indulgence, Tchaikovsky was terrified by the subject of death, and avoided it like a cold sore. According to his old friend Herman Laroche:

“He [Tchaikovsky] had an uncommon dread of death and everything to do with it. He feared anything that even hinted of death, so much so that one could not use any words like coffin, grave, funeral or so forth in his presence.”

Adding to the misunderstanding of the symphony is the nickname that Tchaikovsky himself appended to it. He called it “Патетическая” (Pateticheskaya), which means, literally “the passionate” or “the emotional symphony”. But in the West, “Pateticheskaya” was incorrectly translated into the French “Pathétique”, meaning “pathetic”: something that causes feeling of sadness, grief, or sympathy. (Today’s colloquial definition of “pathetic” – as something unsuccessful, worthless, useless – does not apply!)

We can only wish that Tchaikovsky could have been present at the second performance of the symphony, which was given in his honor in St. Petersburg on November 18, 1893, 12 days after his death and conducted by Eduard Nápravník. The audience response that night was volcanic, and so it has remained ever since.

For lots more on Tchaikovsky, I would direct your attention to my Great Masters biography (currently on sale), produced by The Great Courses.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More