Feast or famine. November 4 is one of those days that is a veritable musical-historical feast, during which so many important musical events took place that we can only wish we could spread them about, so worthy of note are each of them. Among these events are four that I would certainly have written about had not a fifth event pre-empted them.

Here are those four, sadly “pre-empted” events.

Mozart

On November 4, 1784 – 235 years ago today – Wolfgang Mozart completed his String Quartet No. 17 in B-flat major, nicknamed the “Hunt”, K. 458. It is the fourth of the 6 string quartets that Mozart dedicated to his friend and mentor, Joseph Haydn. (Mozart had been inspired to compose those six string quartets by Haydn’s own 6 string quartets of Op. 33, composed in 1781.) Papa Haydn might rightly be called the “father of the modern string quartet” although Mozart should just as rightly be called the “Ayatollah of the modern string quartet” such are the compositional complexity, expressive intensity, and sheer joyful virtuosity of the six quartets he dedicated to Haydn. Joseph Haydn himself was the first person to admit that. When he first heard Mozart’s “Hunt” Quartet performed at Mozart’s central Viennese flat on February 12, 1785 (at Domgasse 5 right around the corner from St. Stephens Cathedral), the 53-year-old Haydn took Mozart’s father Leopold Mozart aside and told him that:

“I, as an honest man, tell you before God that your son is the greatest composer I know in person or by name. He has taste and, moreover, the most thorough knowledge of composition.”

Darn straight.

Brahms

On November 4, 1876 – 143 years ago today – the 43-year-old Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 received its premiere in the German city of Karlsruhe, conducted by his friend Felix Otto Dessoff. The symphony had taken twenty-one years for Brahms to complete, not because he dawdled but because he was pathologically terrified that by going public with a symphony he would be compared to his numero uno hero, the big cahuna, the geeter with the heater, the boss with the sauce, Ludwig van freakin’ Beethoven.

Brahms’ fears were well founded: his Symphony No. 1 was indeed referred to – by both friends and foes alike – as the “Tenth” (as in “Beethoven’s Tenth”). But the symphony was a success, and Brahms’ sympho-phobia thus broken, his final three symphonies followed in comparatively quick succession.

(It was thanks to his Symphony No. 1 that to Brahms’ public horror though secret pleasure, the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow began using Brahms’ name in alliteration with Bach and Beethoven’s, creating for all time “the three B’s”, aka “the killer B’s”.)

On November 4, 1924 – 95 years ago today – the French composer, organist, pianist and teacher Gabriel Urbain Fauré died in Paris at the age of 79. I am a huge fan of Fauré’s music, and so inspired by this anniversary of his death I will feature his superb Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 15 (of 1879 and revised in 1883) in tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post on Patreon.

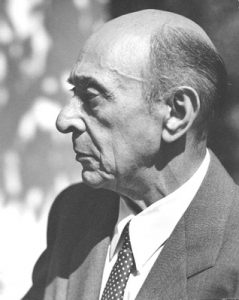

Schoenberg

Finally, on November 4, 1948 – 71 years ago today – Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw for narrator, chorus and orchestra received its premiere in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where it was performed by the Civic Symphony, conducted by Kurt Frederick.

I’ll keep this short, because given the opportunity, I will wax, swoon, and weep inordinately about and over this gut-wrenching masterwork. Schoenberg was born in 1874 into a lower middle-class Jewish family in Vienna. In 1925, he was appointed a professor at the Prussian Academy of Art in Berlin. Adolf Hitler came to power on January 30, 1933, and that was that for Schoenberg’s professorship; on March 17, 1933, Schoenberg and his family left Berlin, never to return.

He ended up in Los Angeles, where he watched – filled with horror and guilt – as the Nazi war machine destroyed much of Europe and European Jewry. Schoenberg’s artistic reaction was to compose a series of truly extraordinary anti-Hitler, anti-Nazi, anti-war musical works, including his Concerto for Piano and Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte for string quartet, piano, and reciter, Op. 41. But nothing, not even the Ode, can match A Survivor from Warsaw for narrator, male chorus and orchestra of 1947. I exaggerate not: this seven-minute, 99 measure-long piece has the impact of a thermonuclear device. In my humble but not ill-informed opinion, it is the most gut-punch powerful, harrowing, heartbreaking and inspirational work composed during the entire twentieth century.

How’s that for a setup? We’ll examine A Survivor from Warsaw in Dr. Bob Prescribes on November 12.

On to the “sonar plexus” of today’s Music History Monday.

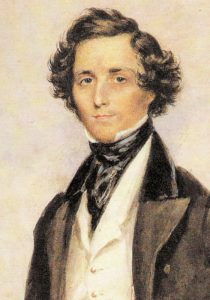

Mendelssohn

On November 4, 1847 – 172 years ago today – Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn died in the Saxon/German city of Leipzig. He died all too soon; at the time of his death Mendelssohn was just 38 years old.

He had never been a particularly healthy person, although in those pre-germ theory days of atmospheric coal dust, lead in everything, dirty water, questionable sewage disposal, fat-and-salt infused diets, tuberculosis and syphilis, it’s a small miracle that anyone managed to survive into adulthood.

In March of 1845, the 36-year-old Mendelssohn was visited by a couple of American travel writers – J. Bayard Taylor and Richard Storris Willis – who were in the process of taking “the grand tour”. Mendelssohn conversed with them in English, and Willis left us with this description:

“[He is a] man of small frame [less than five foot, six inches], delicate and fragile looking; yet possessing a sinewy elasticity, and a power of endurance which you would hardly suppose possible. His head appears to have been set on the wrong shoulders – it seemed, in a certain sense, to contradict his body. [His head is not] disproportionately large, but its striking nobility was a standing reproof to the pedestal on which it rested.”

Bayard Taylor was particularly struck by Mendelssohn’s:

“Dark, lustrous, unfathomable eyes. They were black [and] shining, not with a surface light, but with a pure, serene, planetary flame. His brow, white and unwrinkled, was high and nobly arched, with great breadth at the temples, strongly resembling that of Poe. His nose had the Jewish prominence [italics mine]. The lips were thin and rather long, but with an expression of indescribable sweetness in their delicate curves.”

The first description – Richard Willis’ – dwells on Mendelssohn’s stamina and the seeming fragility of his body. It was an altogether accurate appraisal. Mendelssohn was thin as a rail, a workaholic, and chronically fatigued.

In the summer of 1839 – at the age of just thirty – Mendelssohn suffered what was likely a stroke: while swimming in a cold river, he passed out.

“Unconscious and in convulsions for hours, he was confined to his bed and suffered debilitating headaches for two weeks.”

It took him a month to recover his strength, and the chronic headaches Mendelssohn suffered for the remaining seven years of his life were not a good sign. He suffered from high blood pressure – a family condition – which could not possibly have been helped by his high-stress lifestyle or the high fat/high salt diet typical of the time. The truth be told, Mendelssohn’s health was that proverbial powder keg, waiting to explode; all that was required was the proper spark.

That spark occurred on May 14, 1847, in Berlin. Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny was in the middle of a rehearsal of Felix’ cantata Walpurgis Night when she lost sensation in her hands. This had happened before; she washed them with warm vinegar and then returned to the rehearsal. Minutes later, Fanny’s entire body seized up. Just before she lost consciousness she said:

“It’s a stroke, like Mother had.”

Those were her last words. She died a few hours later, at 11 P.M. that same evening. Fanny was 41 years old.

Background

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (1817-1853) on March 28, 1837. He was 28 years old; she was 20. Cécile was a loving and supportive wife to Mendelssohn; a gifted hostess and visual artist who blessed her husband with five children. Even when allowing for the exaggeration typical of third-party memoirs, Felix and Cécile’s marriage would appear to have been a blissfully happy one. Which tells us that Cécile was not given to jealousy, because she must have understood that the great love of Mendelssohn’s life – his alter-ego, his soulmate, his artistic muse – was his sister, Fanny.

Fanny Cäcilie Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847) was 3 years, 3 months older than her brother Felix. She was hardly less talented than her wunderkind brother, although – tragically – the societal mores of her time precluded her from a professional career in music. (A telling anecdote. In order to get some of her music into print, Felix included a number of her songs in collections published under his name in 1827 and 1830. Years later, in 1842, Felix was the guest of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Buckingham Palace. The Queen expressed her intention of singing what she said was her favorite of Felix’s songs, entitled Italian. An embarrassed silence must have followed before Mendelssohn confessed that the song had actually been composed by Fanny.)

Felix and Fanny were insanely close; for some observers, uncomfortably close. (An article in the prestigious journal The Musical Quarterly dated Winter, 1993 by David Warren Sabean, the Henry J. Bruman Endowed Professor of German History at the University of California, Los Angeles, is entitled “Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and the Question of Incest.”)

According to Mendelssohn biographer Herbert Kupferberg, the relationship between Felix and Fanny was so close that:

“it has engaged the attention of more than one amateur psychologist over the years. Even in their own years, there were jests upon the subject, with several family friends jovially asking the Mendelssohn’s when Fanny’s marriage to Felix would take place.”

So when on May 15, 1847, a messenger brought Felix the news of Fanny’s death he shrieked and collapsed unconscious, apparently having suffered a stroke himself.

Mendelssohn was crushed. He was not physically capable of attending his sister’s funeral in Berlin, and he fell immediately into a depression. He wrote Fanny’s husband, his brother in law, Wilhelm Hensel:

“If the sight of my handwriting stops your tears, put the letter away, for we have nothing left now but to weep from our inmost hearts.”

Mendelssohn and his family escaped to the countryside, first to Baden-Baden and then to Interlaken, in Switzerland. Mendelssohn initially dealt with his grief by drawing and painting watercolors. But by July he knew that it was time to begin composing again. By early September, Mendelssohn completed his final work: a String Quartet in F Minor intended as a memorial to his sister Fanny; the quartet was published as Op. 80

The quartet is a remarkable work in which Mendelssohn’s trademark restraint and elegance are pretty much nowhere to be found. Instead, the piece seethes with sorrow, rage, grief and pain, making it, without a doubt, the single most “autobiographical” work Mendelssohn ever composed.

On October 9, roughly a month after completing the String Quartet in F Minor, Mendelssohn had another stroke and temporarily lost control of his hands while reading through some songs with a singer named Livia Frege. He seemed to be recovering when, 19 days later on October 28, he suffered another, much more devastating stroke. This one left him partially paralyzed and bedridden. Finally, on November 3, he suffered a third stroke which rendered him unconscious. He died the next day, on November 4, 1847, at 9:24 P.M., having outlived his sister Fanny by 174 days. He was 38 years old.

While we know it was a stroke that was the immediate cause of his death, truly, the cliché be damned, Felix Mendelssohn died – 172 years ago today – of a broken heart.

For an in-depth discussion of Felix and Fanny and a detailed analysis of Felix’s masterful Overture to a Midsummer Night’s Dream, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses/Teaching Company course Concert Masterworks, which can be examined and downloaded here at RobertGreenbergMusic.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More