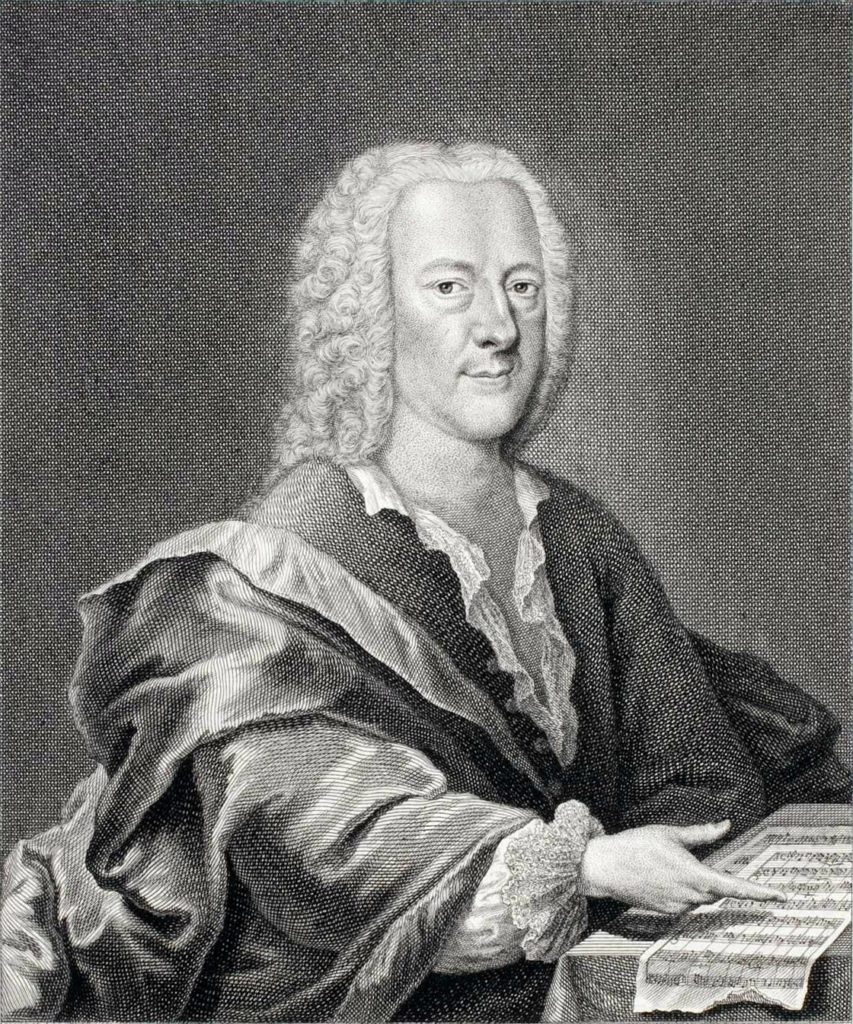

We mark the birth of March 14, 1681 – 341 years ago today – of the German composer Georg Philipp Telemann, in the city Magdeburg, in what today is central Germany. A contemporary of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) and George Frederick Handel (1685-1759) (both of whom Telemann numbered as good friends; Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel was both the godson and namesake of Georg Philipp Telemann), Telemann was considered in his lifetime the greatest composer living and working in Germany, with our friend Sebastian Bach well down that list. Telemann died in Hamburg on June 25, 1767, at the age of 86.

Georg Philipp was the youngest of three surviving children (two boys and a girl) of Maria and Heinrich Telemann. Young Telemann came from a long line of Protestant clergymen. His mother Maria’s father was a deacon, and his father Heinrich Telemann was a Lutheran pastor (as was Heinrich’s father before him). Sadly, Heinrich Telemann died his late 30’s in 1685 when Georg Philipp was just 4 years old, and the task of raising and providing for the family fell squarely on Maria Telemann’s shoulders.

Single mothers are usually, by necessity, a tough bunch, and in this Maria Telemann was no exception. Despite the fact that her youngest child Georg Philipp displayed prodigious musical talents from a young age, she took it for granted that like his father and both his grandfathers before him, young Telemann was destined for the cloth and a career in the clergy.

But as is so often the case, the young Georg Philipp Telemann had other ideas. By the age of 12, he had been taught to sing and play keyboards. He had, as well, taught himself to play recorder, violin, and zither; and on his own had learned the principals of composition sufficiently to have composed various arias, motets, and instrumental works. At the age of 12 he composed his first opera entitled Sigismundus to a libretto by the German poet and librettist Christian Heinrich Postel (1658-1705).

(In 1739, the 58-year-old Telemann wrote a brief autobiography. Regarding his opera Sigismundus he wrote:

“This [opera] was performed with a measure of éclat on an improvised stage, with me singing a rather arrogant version of my own hero. I really would like to see that music now . . .”)

That’s some serious talent, but rather than be proud of her precocious son and his musical aspirations, Momma Telemann freaked out. Terrified that Georg Philipp was headed for a career in music, having “produced” his opera at the age of 12, his mother forbade him from having any further contact with music and confiscated his musical instruments. Telemann later described it this way:

“Done! Music and instruments were whisked away, and with them half my very life.”

But Georg Philipp was wily, or at least so he thought he was. He composed secretly at night and practiced on borrowed instruments in seclusion:

“My fire burned far too brightly, and lighted my way into the path of innocent disobedience, so that I spent many a night with pen in hand because I was forbidden it by day, and passed many an hour in lonely places with borrowed instruments.”

But in the end Georg Philipp fooled no one, not least his mother Maria, who was enraged by her son’s “innocent disobedience.” Extreme measures were called for. So she wrote her husband’s old friend and university classmate Caspar Calvoer in the town of Zellerfeld, about 50 miles southwest of Magdeburg. Calvoer was the superintendent of a school there in Zellerfeld, and he agreed to not just accept the now 13-year-old Georg Philipp, but to personally oversee his education.

We imagine that Maria Telemann sighed with relief. Calvoer was a theologian, historian, mathematician, and a writer with a number of scientific papers and publications to his credit. Maria would seem to have had no idea that Calvoer had applied himself as well to a study of music and had written several papers on medieval music theory.

Oops.

According to Telemann biographer Richard Petzoldt (Georg Philipp Telemann, Oxford University Press, 1974):

“Casper Calvoer rejoiced at his protégé’s musical gift. With Calvoer’s approval, the boy once again set about practicing his instruments, regularly writing pieces for the church choir, as well as [works] for the town musicians and occasional pieces for celebrations, weddings, and the like.”

We don’t know how Maria Telemann reacted when she became aware of the situation with Calvoer in Zellerfeld, although we can safely assume she reacted poorly. We do know that seven years later, when Telemann was twenty and preparing to enter Leipzig University, she again demanded that he “leave music [and] abandon his entire musical household” in order to study law. But in the end, she was no more successful turning her son away from music when he was 20 than when he was 13, and we are all the richer for that fact.…

Continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More