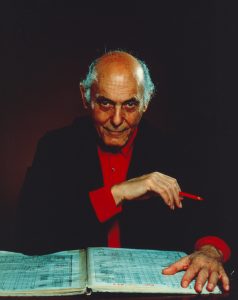

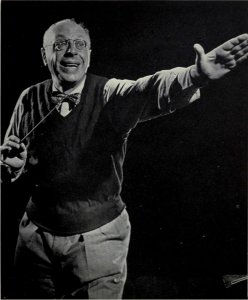

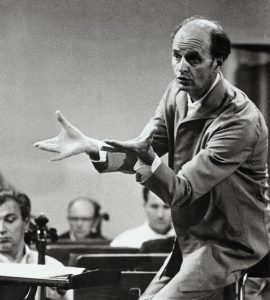

We mark the birth, on October 21, 1912 – 107 years ago today – of the Hungarian-born pianist and conductor György Stern (better known as Sir Georg Solti) in Budapest, Hungary. Considered one of the greatest conductors to have ever lived, Solti is the Michael Phelps, the Simone Biles of the musical world, having received a record 31(!) GRAMMY® Awards.

We contemplate, for a nonce (or even two nonces), “disproportionate numbers”: why and how certain relatively small populations produce large numbers of great performers.

For example.

The Dominican Republic, the Caribbean nation that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. In 2017, the World Bank put the Dominican Republic’s population at 10.77 million people, making it equal to the population of North Carolina. Yet, incredibly, over 10% of the active players in Major League Baseball are of Dominican origin. Even a partial list of past and present Dominican baseball players reads like a catalog of the very best and brightest, a catalog that should make any baseball fan shiver with gratitude: the Alou brother, Felipe, Matty, and Jesus; Juan Marichal; Pedro Martinez; Vladimir Guerrero; Rico Carty; George Bell; Manny Mota; César Cedeño; Tony Peña; Sammy Sosa; David Ortiz; Manny Ramirez; Robinson Canó; Albert Pujols; Miguel Tejada; Bartolo Colón; José Bautista; Julio Franco; Melky Cabrera; Francisco Liriano; Edwin Encarnación; and Johnny Cueto (to name but a few!).

Why are there so many great Dominican baseball players? With 40% of the Dominican population living in poverty, baseball is perceived as the “field of dreams”: a ticket out into wealth and stardom. But that’s all it would be – a “dream” – if there wasn’t a Dominican culture that worships baseball perhaps to a fault, a player development infrastructure in place to teach and train these young athletes, and a climate that allows that training to go on 12 months of the year.

Disproportionate numbers.

Nine days ago, on October 12, the Kenyan long-distance runner Eliud Kipchoge did the once unthinkable when he ran a sub-two-hour marathon, clocking in at 1:59:40 (Kipchoge already held the “official” world record for a marathon, 2:01:39, set in Berlin in 2018. In doing so, he broke a record set by his fellow Kenyan Dennis Kipruto Kimetto in 2014. In setting his record, Kimetto broke a record set by his fellow Kenyan Patrick Makau Musyoki. Are we seeing a pattern here?).

Kenyan women marathoners are hardly less dominant than the men.

Why are so many of the world’s greatest marathoners from the Western Rift Valley highlands of Kenya (and, for that matter, the adjacent highlands of Ethiopia?)

Various explanations have been put forth. Once again, poverty plays a role: competitive running offers a way out for a successful athlete. The distances between villages, schools, and stores and a lack of ready transportation requires that children in these regions walk (and run) barefoot for considerable distances on a daily basis. Living and working and running at the high altitudes in which they live has given these Kenyans (and neighboring Ethiopians) an almost off-the-charts VO2 max, meaning the maximum amount of oxygen an individual can utilize during intense exercise. Put these good people down at sea level and they can – as they have proven over and over again – run circles around most of their competitors.

Disproportionate numbers.

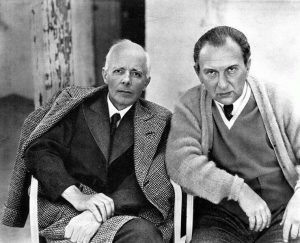

In 2017, the population of the nation of Hungary sat at under 10 million people, making it less populous than the Dominican Republic. And yet this relatively small nation produced a large proportion of the greatest conductors of the twentieth century, all of whom were born into Jewish families in the Hungarian capital city of Budapest: Frederick Martin “Fritz” Reiner (born Frigyes Reiner, 1888-1962); George Szell (born György Endre Szél, 1897-1970); Eugene Ormandy (born Jenő Blau; 1899-1985); Antal Doráti (1906-1988); Ferenc Fricsay (1914-1963); and Georg Solti (born György Stern, October 21, 1912-September 5, 1997).

By any measure, this is an astonishing group of conductors.

I would suggest that as members of an ethnic and religious minority, born just a generation or two off the shtetl, the drive for excellence and success was inculcated in these dudes by their upwardly mobile families from the youngest age. Given prevailing American values, had they been born in Philadelphia, or New York, or Boston they might have grown up to be doctors, or lawyers, or businesspeople. But they were born in Budapest at a time when many professions were still, for all intents and purposes, off-limits to Jews. But music was not off-limits, and to a degree that many Americans would find difficult to fathom, concert music was considered a singularly noble pursuit. And it just so happened that Budapest was one of the most musical cities on the planet with a musical educational infrastructure that was second-to-none.

We would recall that from 1867 until 1918, the “Austrian Empire” was, in fact, the “Austro-Hungarian Empire”, the so-called Dual Monarchy, with two capital cities: Vienna and Budapest. Because of its long and glorious musical history, we take for granted that Vienna was the musical capital of central Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But in fact, Budapest was not far behind, and when it came to music educational institutions, Budapest was, if anything, ahead of Vienna. Chief among those institutions was the “Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music” which was founded in 1875 and which in 1925 was renamed the “Franz Liszt Academy.” (It has also been known as/referred to as the “Budapest Academy of Music” and the “Budapest Conservatory.”)

During the 19-teens, 20s, and 30s, the faculty at the academy included such luminaries as Béla Bartók, Zoltan Kodály, and Ernő Dohnányi. Indeed, if we are to judge an educational institution by the accomplishments of its graduates, the Franz Liszt Academy must be judged as one of the greatest and most important music schools ever! Check it out:

Fritz Reiner studied piano, piano pedagogy and conducting at the Academy; during his last two years, his principal piano teacher was Béla Bartók.

Eugene Ormandy began studying violin at the Academy in 1904, when he was five years old (when the school was still called the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music). He graduated with a master’s degree in violin at the tender age of 14! (For our information: Ormandy moved to the United States in 1921 at the age of 22 where, along with his bud and fellow Academy graduate Erno Rapee, he joined the 77-member orchestra of the Capitol Theater in New York City as a violinist, where he accompanied silent movies; four shows a day; seven days a week.)

Antal Doráti attended the Liszt Academy as well, where he studied piano with Bartók and composition with Kodály.

Ferenc Fricsay cut a broad path at the Liszt Academy, where he studied piano, violin, clarinet, trombone, percussion, composition and conducting with, among others, Béla Bartók, Zoltan Kodály, and Ernő Dohnányi. Whoa.

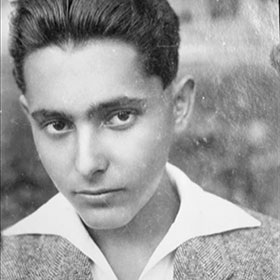

Georg Solti took up the piano early on, though by his own admission he was not a diligent student. In his memoirs, he wrote:

“My mother kept telling me to practice, but what ten-year-old wants to play the piano when he could be out playing football?”

(It’s a very good question.)

Solti must have practiced enough, though, because at the age of 12 he entered the Franz Liszt Academy, where he studied piano with Béla Bartók and composition with Ernő Dohnányi.

(The only one of the Hungarian Hebrew conductorial Mafiosi born in Budapest that did not study at the Franz Liszt Academy was George Szell, who though born in Budapest to Hungarian parents, grew up in Vienna.)

Bless them, every one of these conductors survived World War Two. For Fritz Reiner and Eugene Ormandy, no particular hardships were involved. Reiner moved to the United States in 1922 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1928. As we’ve already observed, Ormandy came to the United States in 1921. Within a year of his arrival he applied for citizenship, which he was granted soon after. For our info, in 1970 Ormandy received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

When World War Two began in Europe on September 1, 1939, George Szell serendipitously found himself in the United States; he was on his way back to Europe after a tour of Australia. He and his family stayed, settling in New York, where Szell taught at the Mannes School of Music. In 1946, Szell became both a naturalized citizen of the United States and Music Director of the Cleveland Symphony, a position he held until his death in 1970.

In 1929, at the age of 23, Antal Doráti became the music director at the opera house in the German city of Münster in North Rhine-Westfalia, Germany. Doráti resigned his position when Hitler came to power in 1933 and in 1941 became the Music Director of the American Ballet Theater in New York. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1947.

Ferenc Fricsay remained in Hungary which was almost his undoing. Nazi Germany occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944 in order to compel their presumed ally, the Hungarian strong-man Miklós Horthy, to ship Hungary’s sizable Jewish population to the deathcamp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Fricsay received advanced warning that he was to be arrested, and he and his wife Marta and their three children managed to go underground in Budapest, and thus they survived the war.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Georg Solti was working as an assistant to the conductor Joseph Krips in Karlsruhe, Germany. Krips told Solti that he was no longer safe in Germany, and insisted that Solti return to Budapest, which he did. Given Hungary’s friendship pact with Hitler’s Germany, Solti eventually decided that Hungary was no safer a place for him than Germany, and he waited out the war years in Switzerland. With Hungary under Soviet control after the war, Solti refused to return and became stateless. Rather ironically, then, Solti found post-War employment in Germany, and became a West German citizen in 1953. In 1972 he became a British citizen, and so he remained until his death in 1997.

A tidbit. Solti was what might euphemistically be called a “very demanding conductor.” In translation, that means that he yelled a lot. That “demanding conducting style” combined with his bald head earned him the rather Halloweenish nickname “The Screaming Skull.”

He might have been a pill, but dang if he wasn’t a great conductor. So happy birthday, Maestro Screaming Skull!

For lots more on the impact of current events on the development of music, I would humbly suggest you check out my Great Courses/Teaching Company survey, Music as a Mirror of History at RobertGreenbergMusic.com and to subscribe on Patreon.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More