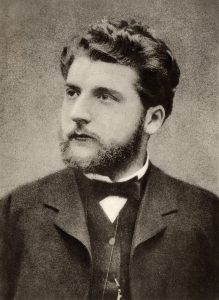

We mark the death of the French composer Georges Bizet, who passed from this vale of tears on June 3, 1875, 144 years ago today. He was but 36 years, 7 months, and 9 days young when he passed.

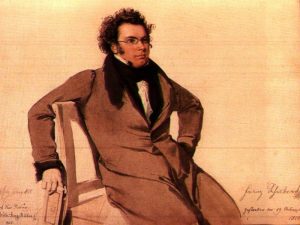

The title for today’s post is the epitaph that appeared on Franz Schubert’s original tombstone, written by Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872):

“Here music has buried a treasure, but even fairer hope.”

Ain’t that the truth. Schubert’s life-span was even shorter than Bizet’s: 31 years, 9 months, and 20 days.

(Grillparzer was a Vienna-born dramatist who, despite his contemporary fame as a playwright, is best remembered today for having written Beethoven’s funeral oration and Schubert’s epitaph!)

We contemplate “regret”.

I am a collector of certain antique/vintage items, and I have learned the hard way the truism that “you only regret that which you do not buy.” For example, I will go to my grave regretting the fact that I walked away from a complete, pristine Sterling Silver Erik Magnussen “Skyscraper Cocktail Set” in 2003.

I had my reasons (financial) for not buying the set at the time, but it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, never to be had again; should a like set come to market again, it will go for ten to twenty times the amount I could have bought it for. Dang. Double dang.

I regret not having taken that plunge.

(Yes, I know: this does not really qualify as a problem. I am, however, reflecting on the nature of “regret.”)

As emotions go, on a scale of ten (one being grief; ten being euphoria), I would rank regret at about a four: a generally negative emotion that, nevertheless, is useful if it allows us to avoid a like mistake in the future.

Back to the Music

Back to Georges Bizet, Franz Schubert, and that gaggle of other great (or potentially great) composers who died before turning forty: Henry Purcell (dead at 36), Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (26), Wolfgang Mozart (35), Vincenzo Bellini (33), Frédéric Chopin (39), Felix Mendelssohn (38), Lili Boulanger (24), Juan Arriaga (19), and George Gershwin (who died at the age of 38). All of us should deeply regret their early passing, and find it well-nigh impossible not to reflect on what they might have accomplished had they at least lived for Beethoven’s life span (56 years), or Sebastian Bach’s (65 years), or Richard Strauss’ (85 years), or Elliott Carter’s (103 years) or Leo Ornstein’s (106 years!).

I don’t know about you, but not only do I regret the early deaths of these composers, but I can’t help but feel regret over what they might have created had they lived longer lives. And while I would think that most of us feel the same way, I know that not everyone actually does. For example, apropos of Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann wrote back in the mid-nineteenth century that:

“It is pointless to guess at what more Schubert might have achieved. He did enough; and let them be honored who have striven and accomplished as he did.”

Rather more recently, the pianist András Schiff said that:

“Schubert lived a very short life, but it was a very concentrated life. In 31 years, he lived more than other people would live in 100 years, and it is needless to speculate what could he have written had he lived another 50 years. It’s irrelevant, just like with Mozart; these are the two natural geniuses of music.”

At very least, I would accuse Messrs. Schubert and Schiff of being intellectual party-poopers, by denying us all the exercise of regret and speculation. But I also find their dismissive, self-righteous attitudes irksome and their assertions that speculation is “pointless”, “needless” and “irrelevant” downright wrong.

Why “wrong”? Because speculating on “what if” allows us to formulate alternative outcomes, alternative outcomes that help us to recognize and process more deeply what did happen.

(Of course, if the American theoretical physicist and string theorist Brian Greene is correct, and we live in a “quilted multiverse”, then any possible event will occur an infinite number of times in an infinite number of parallel universes. If this is actually true, there is no such thing as “speculation”, as anything we can “speculate on” will indeed occur in some universe or another!)

Back to our cozy universe. To my mind, far from being merely sport, speculating on possible outcomes allows us to sharpen our understanding of what did happen and to appreciate the incredible web of interactive cause-and-effect that characterizes historical progression.

For example, back to Schubert. He contracted syphilis sometime in the late summer of 1822 at the age 25. It was a bad case from day one; physically and psychologically, Schubert suffered mightily. Harsh as it might be to say, Schubert’s pain was our gain: his infirmity drove his music to an entirely new expressive level, one that rivalled that of Beethoven. And then for nearly three years – from the fall of 1824 until mid-1827 or so – Schubert’s disease entered its latency, during which he was symptom free and noninfectious. Well, what if: what if Schubert had been one of the very few lucky ones whose latency was permanent? (It was not; he entered his tertiary stage in the summer of 1827 and died in November of 1828.)

But what if – like Beethoven – he had lived to be 56 years of age and had therefore died in 1853? Obviously, Schubert would have composed lots more music – symphonies, piano sonatas, string quartets, vocal music of all sorts etc. – music that would almost certainly have continued to exhibit his paradoxical synthesis of Classical melodic grace and Beethovenian expressive oomph. Had he lived into the mid-century, he would have personally encountered and worked with Schumann, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Liszt, perhaps even Brahms. The model of Schubert and his music would have become a viable alternative to that of Beethoven; perhaps Schubert would have actually replaced Beethoven as the pre-eminent German-speaking composer of the nineteenth century.

But of course, Schubert did die in 1828, and it was Beethoven and his music that became emblematic of a heroic German self-image. It was a self-image that gave musical impetus to not just Wagner and Brahms but was employed by nationalist politicians to create a heroic myth for the nascent German nation. Would the nature of nineteenth century German nationalism – which was to have such a catastrophic impact on the twentieth century – would the nature of nineteenth century German nationalism have been altered had Schubert lived and continued to compose?

We’ll never know. But such speculation allows us to address the degree to which media – in this case, concert music – can affect national myth, national self-image, and can be used by demagogues for ultimately nefarious ends.

Georges Bizet

Georges Bizet was born in Paris on October 25, 1838 and died there on June 3, 1875. A piano prodigy, he was a star at the Paris Conservatoire, and capped his educational career with the coveted Prix de Rome – the Rome Prize – which included a two-year residency at the Villa Medici, the official home of the French Académie in the Eternal City.

His spectacular talent notwithstanding, Bizet had to struggle like the rest of us once his Rome Prize money ran out. He taught piano; worked as a rehearsal pianist for opera and ballet companies, and transcribed countless opera and ballet scores for piano.

You want to talk about a difficult apprenticeship? His first six operas remained unperformed at the time of his death. His seventh opera – entitled The Pearl Fishers (1863) – is often referred to as his “first opera”, but that’s only because it was the first one to be performed, at Paris’ Théâtre Lyrique on September 30, 1863.

Seven more operas followed, though only two of them were completed and performed in Bizet’s lifetime. All in all, his was a questionable operatic legacy, at least until 1874 when, at the age of 36, he completed Carmen.

Carmen: how do we love thee? Let us alphabetize the ways! Astounding, brilliant, celebrated, dazzling, exceptional, first-rate, glorious, hellaciously fine, incredible, and justly-famous, although you wouldn’t have known it from the reviews. First performed on March 3, 1875 at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, Carmen was slammed for being too Wagnerian (critics wrongly complained that the voices were subordinated to the orchestra), amoral (because the title character was a sluttish libertine – a veritable female Don Giovanni – and not a woman of virtue!), and that the music itself was boring; according to Léon Escudier in L’Art Musical, Carmen‘s music:

“is dull and obscure; the ear grows weary of waiting for the cadence that never comes.”

Dine on cow pie, dude.

The reviews kept audiences away in droves, and what small audiences did attend the opera’s first run remained unenthusiastic. If it is possible to die from a broken heart, Bizet did: he dropped dead from a heart attack on June 3, 1875, three months to the day after Carmen received its premiere.

Bizet’s sudden death is cause for deep regret, because Carmen’s fame was right around the corner.

Just days before he died, a downcast Bizet had signed a contract to produce Carmen in Vienna. The opera opened there 4½ months after he died, on October 23, 1875 and it was a smash hit. Wagner heard it, and wrote:

“Here, thank God, at last for a change is somebody with ideas in his head.”

Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms rarely agreed on anything, but they did agree on Carmen. Brahms reportedly saw the opera twenty times and wrote that he would have:

“gone to the ends of the earth to embrace Bizet.”

Johannes Brahms and Peter Tchaikovsky rarely agreed on anything, but they also agreed on Carmen. Tchaikovsky wrote:

“Carmen is a masterpiece in every sense of the word … one of those rare creations which expresses the efforts of a whole musical epoch.”

(The German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck claimed to have seen Carmen 27 times; the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that he “becomes a better man when Bizet speaks to me.”)

Carmen remains one of the most popular operas in the repertoire, and for good reason. The music is glorious; the characters are beautifully drawn; and in it, Bizet displays the same miraculous ability as Mozart and Verdi to make us, his audience, engage and identify with the emotions and the pain felt by his characters.

With the passing of time we – as an audience – have come to realize that Bizet was not the one-hit wonder he was considered to be in the years immediately following his death. His unperformed music has been performed, and music that was thought to be lost has been discovered and played. (For example, Bizet’s delightful Symphony in C – which he completed just a month after he turned 17 – was lost after his death. It was only discovered in 1933, and first performed in 1935.)

So let us speculate.

France had no shortage of competent opera composers during the last quarter of the nineteenth century: Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921); Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894); Alfred Bruneau (1857-1934); and Gustave Charpentier (1860-1956).

But the big operatic poisson of the time was Jules Massenet (1842-1912), who composed a total of 33 operas, 26 of which were produced. Outside of France, only Manon (named for the title character who, like Carmen, is a very naughty girl), is still regularly played. Writes Harold Schonberg:

“[Massenet’s operas feature] leitmotifs à la Wagner, sentimental melodies à la Gounod, an orchestra that produced soothing and sensuous sounds, a libretto that could titillate the tired businessman yet send him out of the theater morally uplifted.”

Bizet’s Carmen is a very different sort of opera than those of Massenet or, for that matter, any of the French opera composers just mentioned. Carmen is a verismo (meaning “realism”) styled opera far ahead of its time. (The great master of Italian verismo, Giacomo Puccini, was just 16 years old when Bizet completed Carmen.) If Bizet had continued down the verismo path begun in Carmen, it seems very likely that late nineteenth century French opera would have steered a more dramatic course than the confections of Massenet and would have rivalled – if not outdone completely – the works of the principal Italian verismo composers: Mascagni, Leoncavallo, and Puccini. Further, the international acclaim that Carmen generated – particularly in Austria and Germany – might have helped to lift France out of its traditional artistic insularity and at the same time have given audiences in Austria, Germany and France something in common with each other. In those decades before the cataclysm of August 1914, points in common between France and the German-speaking nations were in sorely short supply.

What if.

We give the musicologist and Bizet biographer Hugh Macdonald the last word:

“The spectacle of great works unwritten either because Bizet had other distractions, or because no one asked him to write them, or because of his premature death, is infinitely dispiriting [which is another way of saying ‘a cause for regret’], yet the brilliance and the individuality of his best music is unmistakable. It has greatly enriched a period of French music already rich in composers of talent and distinction after his death.”

For more on nineteenth-century opera, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, How to Listen to Great Opera.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More